The Hunter Brothers of the 49th Battalion: A WWI Story

By Alaine Baldwin, Visitor Services Assistant, Anzac Square Memorial Galleries | 26 June 2023

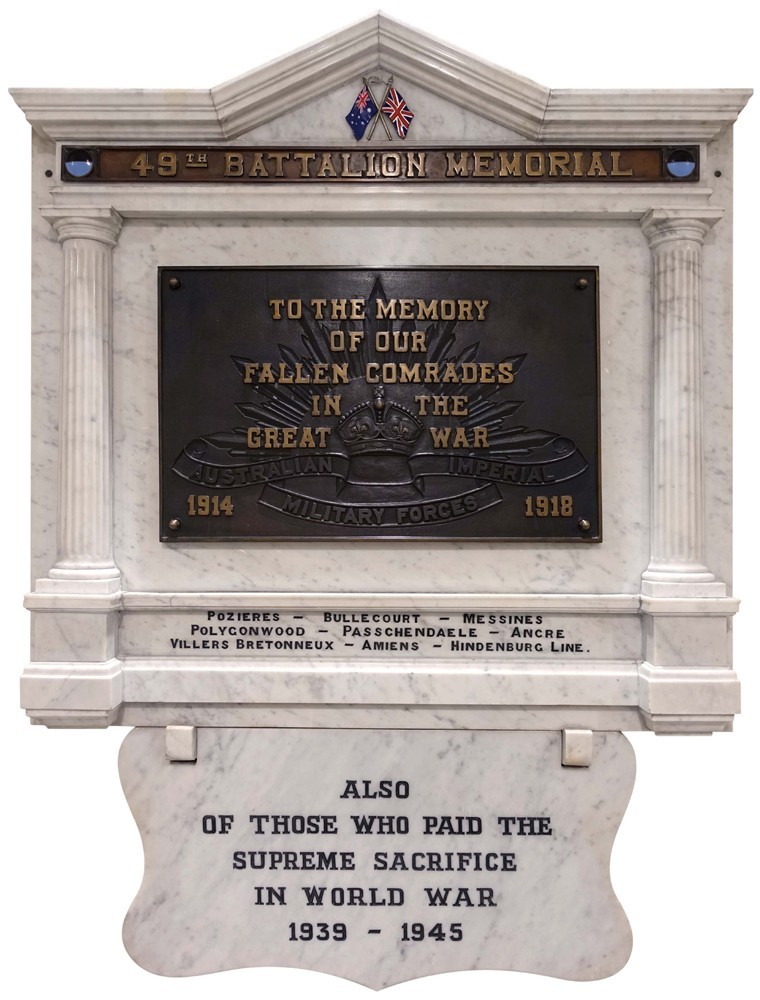

The 49th Battalion plaque at Anzac Square Memorial Galleries.

The plaque for the 49th Australian Infantry Battalion has hung on the wall of Anzac Square Memorial Galleries since 3 March 1935 and commemorates members of the 49th who died in service or were killed in action during WWI and later in WWII. There is an extensive Roll of Honour surrounding the main plaque, and one of the names listed for WWI hides a fascinating story.

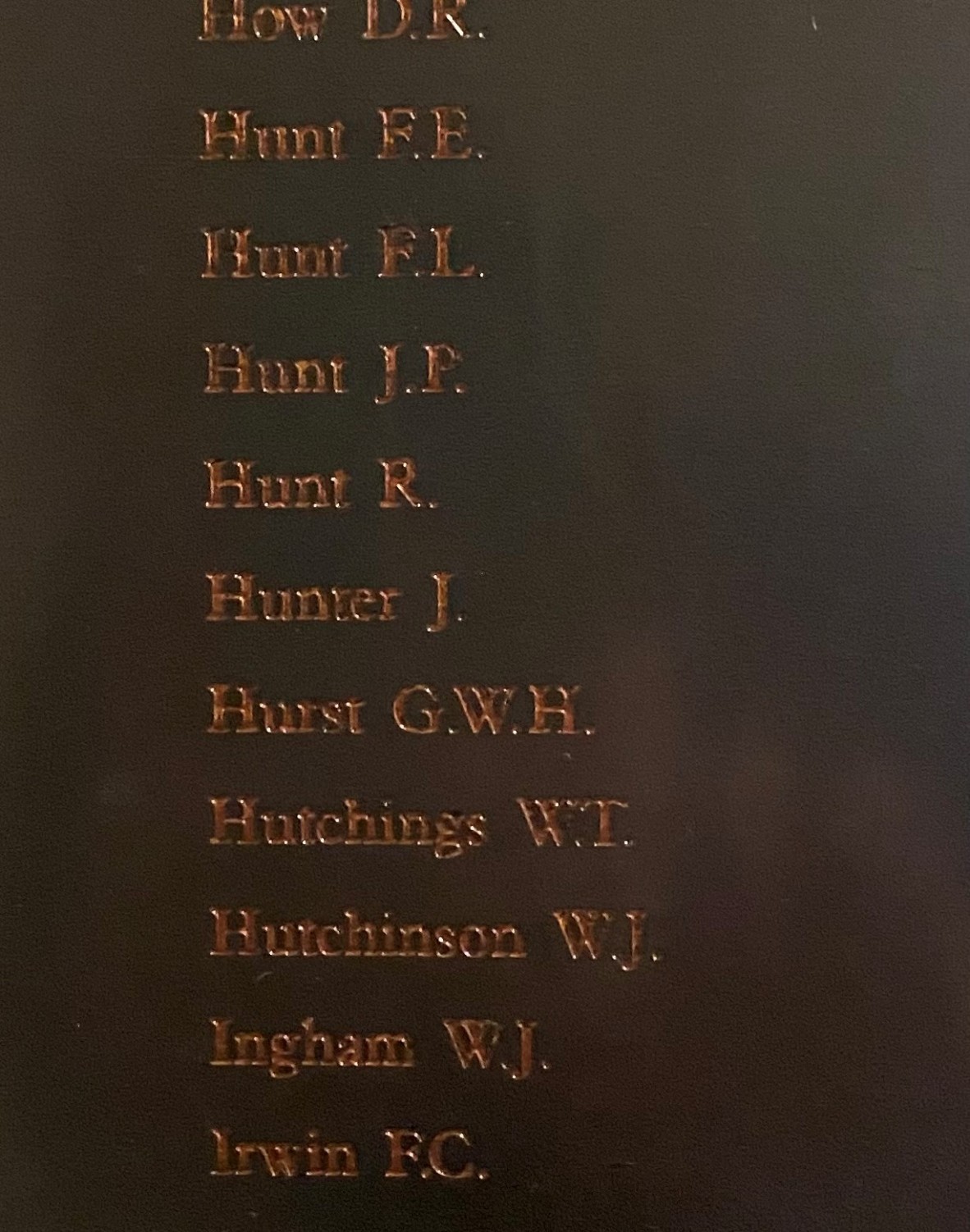

Honour roll for the 49th Battalion. Image by Anzac Square Memorial Galleries.

The inscription Hunter J. is for John (Jack) Hunter from Nanango who joined the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) on 25 October 1916, two days after his younger brother James (Jim), itching for adventure, had signed up against his father’s wishes. Jack, the oldest of the 7 Hunter children, worked with his widowed father and had felt his place was at home. However, Jim’s determination to do his bit by enlisting prompted Jack to sign up as well, promising his father he would look after him.

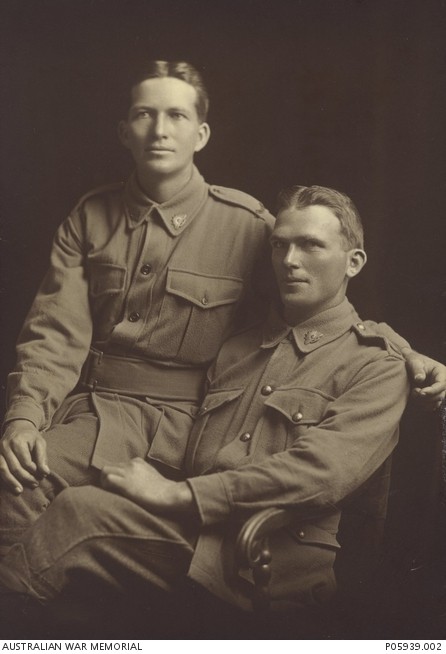

Studio portrait of 3504 Private John Hunter and his younger brother 3497 Private James Hunter (left) of Nanango, 9th Reinforcements, 49th Battalion, 1916, Australian War Memorial, PO5939.002.

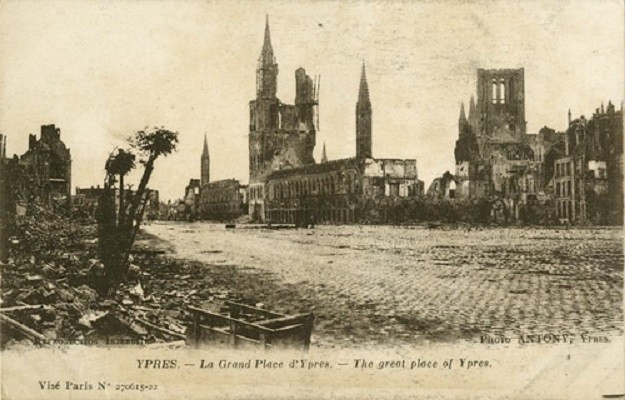

The Hunter boys, at that time aged 27 and 25, would form part of the 9th Reinforcements for the 49th Battalion. After being farewelled in Nanango they rode the 10 hours to Brisbane before catching the train to Sydney. Here the ‘adventure’ would begin. They embarked from Sydney on HMAS Ayrshire on 24 January 1917 and arrived in the UK on 12 April. Three and a half months was spent at the Salisbury Plain training camp learning tactics for trench warfare and the use of gas masks. The brothers proceeded overseas to join the 49th Battalion in West Flanders on 6 August 1917 and were shocked by the devastation they saw as they marched towards Ypres.

A postcard featuring a photograph of the devastation of the town of Ypres, Belgium, 1917, from the Una Margaret Stitt Collection, State Library of Queensland, Negative: 30413-0051

They joined the 49th on 25 August and weren’t called to the front line until late September when they would be part of a major push to dislodge the Germans from Polygon Wood. At dawn on 26 September, prior to the main battle, Jack was ordered ‘over the top’ into no man’s land to retrieve a tin that was reflecting in the sights of the Allies' guns. As he ran back towards the trenches, he was hit by shrapnel from a mortar shell and Jim saw him tumble into the trench not far from where he was standing.

Jim reacted immediately and with the help of another soldier got Jack onto a stretcher. They carried him for nearly a kilometre over duckboards, avoiding the shells and bullets that signalled the start of the Battle of Polygon Wood. However, by the time they reached the nearest dressing station, Jack had already died. A wide shallow grave was prepared for Jack and several other soldiers. After crossing Jack’s hands over his heart, Jim wrapped his beloved brother in a ground sheet and secured it with signal wire before lowering the body into the mass grave. Making sure to take note of landmarks near the grave, he vowed to return and retrieve his brother when the war ended.

Australian troops in forward positions near Zonnebeke during the Battle of Polygon Wood, 26 September 1917 (the day Jack was killed).

Jim survived bullet wounds and mustard gas poisoning as the war raged on along the Western Front, and it wasn’t until March 1919 that he returned to the Polygon Wood region hoping to find his brother’s body and take it home. Unfortunately, the landscape had changed significantly, and a road had been built over the location of Jack’s grave. Desperately disappointed, Jim returned to Australia on 8 June 1919 determined to live the life his brother never would. This he achieved by marrying and raising his six children. He lived to the age of 86, dying in 1977. However, the loss of his brother was constantly with him, and his niece Mollie Millis recalls him calling for Jack on his deathbed.

Interestingly, Jim always believed that his brother’s body would turn up one day and it did. The bodies of five Australian soldiers were discovered in September 2006 during a pipeline excavation near Westhoek, Belgium. A local WWI enthusiast, amateur archaeologist, and proprietor of the Anzac Rest café in Flanders, Johan Vandewalle, ensured the site was preserved and excavated properly. Vandewalle noticed one body was wrapped in a rubber groundsheet and secured with wire. As he removed the rubber sheet, he saw the hands had been placed across the soldier’s chest. These obvious signs of care and tenderness inspired him to make it his mission to find out who this soldier was. The soldiers were identified from a uniform badge as members of the 4th Division of the AIF, but a lack of personal effects meant the task of identification went to the Australian Army History Unit. Through detailed research they found seven missing soldiers who the bodies under the road could be. Their names were published in the media across Australia in 2007.

Jim’s niece, Mollie Mills saw the list of names in her local newspaper, and thinking the John Hunter might be her uncle ‘Jack’ contacted the history unit. Through DNA testing it was confirmed the wrapped body was Jack. Finally, in October 2007, 90 years after his death, Jack was laid to rest at the Buttes New British Cemetery at Polygon Wood. The ceremony, with full military honours, was witnessed by Mollie and Jim’s son, James Hunter. The words, “At rest after being lost for 90 years” were engraved on his tombstone and his name was crossed off the list of ‘missing’ on the Menin Gate.

Headstone of #3504 Private John (Jack) Hunter and the other soldiers discovered in the mass grave, Buttes New British Cemetery, Polygon Wood. Photo taken by member of the Anzac Square Team, 13 October 2017.

Vandewalle attended the reburials and met members of the families. He then decided to travel to Australia to meet more people related to them. It was while he was in Australia that he heard the story of Jim burying his brother from Jim and Jack’s relatives.

Touched by the story of the Hunter brothers, Vandewalle and a team of WWI enthusiasts decided to establish a memorial to the memory of the thousands of brothers who served together and suffered like the Hunter boys during the war. In 2010, they started raising funds for the memorial they envisaged. The ‘Brother’s in Arms Memorial Project’ was established and in November 2021 one of the final pieces, a beautifully carved bronze sculpture of the Hunter brothers left Melbourne bound for the memorial in Belgium. The design of the sculpture was thought of by Johan Vandewalle and executed by Australian sculptor Lois Laumen.

Sculpture of Jack Hunter in the arms of his younger brother Jim created by Australian sculptor Louis Laumen. Situated in the Brothers-in-Arms Memorial Zonnebeke, 2022. Image: Brothers in Arms Memorial official website n.d., https://www.brothersinarmsmemorial.info, viewed 26 June 2023.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.