The House that moved: Queenslander houses and the curious practice of house relocation

By Christina Ealing-Godbold, Research Librarian, Information and Client Services | 21 December 2024

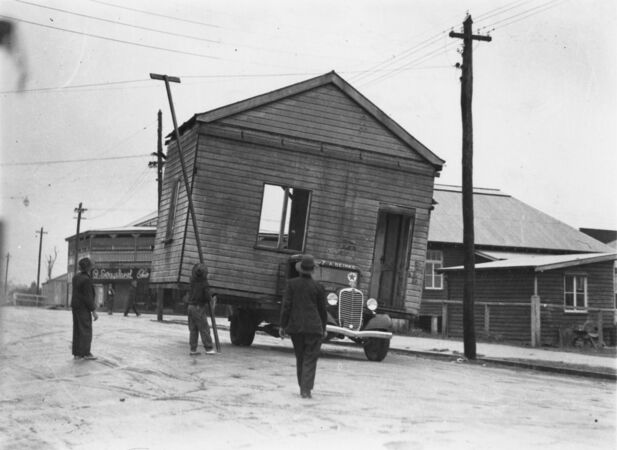

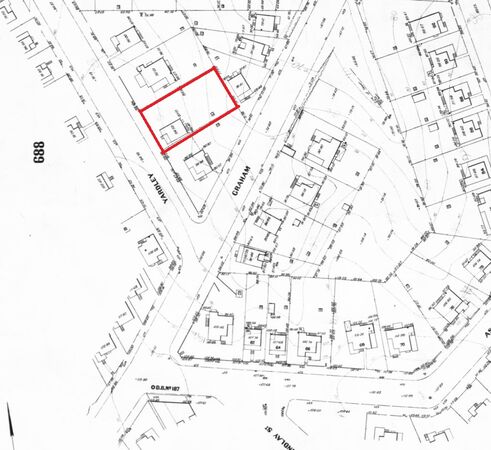

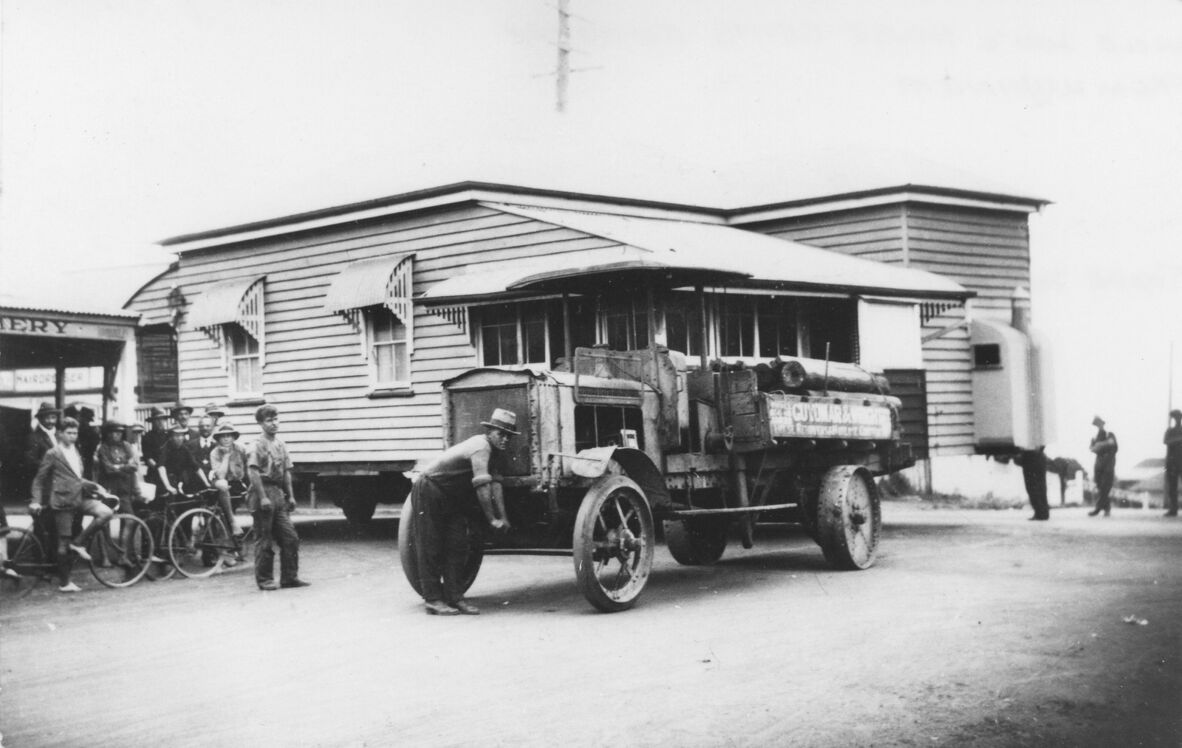

House being moved by a Renard road train engine on a suburban street, North Ipswich, Queensland, October 1923.

The weatherboard Queenslander house has been very often moved over the generations. Unlike brick homes, weatherboard and corrugated iron Queenslanders were able to be cut into sections, placed on the back of a truck and moved to a more convenient location. Moving houses from the inner city to the country has been a popular way of obtaining an old Queensland house in a chosen location for more than a century. While not strictly confined to Queensland (some houses were moved in other states on occasion), the practice of house removal did become a part of the Queensland lifestyle and was especially prevalent in the First World War era, during the economically challenging years of the 1930s, and in the 1970s when urban renewal provided many older unwanted Queenslander houses available for relocation.

The moveable Queenslander house was a feature of the developing extensive frontier society in the 19th and 20th century and allowed for expansion and adjustment where required. This feature of Queensland social history was often observed by visitors and tourists as a curious aspect of life in the northern state.

The reason for moving houses was primarily economic. Buying a house for removal was much cheaper than having a new home constructed. In the 1920s, a small wooden home could be purchased for around £70, whereas a new home built from plans published at the time could cost upwards of £300. Today, removal houses can cost anything from $70,000 up to $300,000. Of course, the costs of re-plumbing and re-stumping and other relocation charges may also apply.

However, the reason for the relocation of homes was also a practical requirement of developing towns, cities and pastoral properties as circumstances changed over decades. Some areas of inner-city Brisbane were targeted for house clearing. One such location was the South Brisbane area prior to Expo 88 and another the Gregory Terrace precinct when the Royal National Association expanded it grounds. The construction of freeways, tunnels and railway lines also all required resumption of land and the houses upon them throughout the decades.

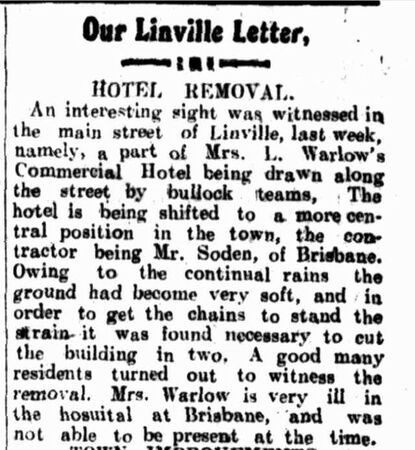

In rural Queensland, land was often leased (there were a number of differing pastoral leases) and so a weatherboard house could be moved to an adjoining leasehold if necessary. Likewise, townships were provisional and could be moved slightly in response to railway lines, highway positioning or water catchments. The hotel or community hall needed to be at the centre of the township and so movement was sometimes necessary to reposition town buildings. When the railway was forging westwards, in rural Queensland, the township at the railhead would be moved further out as lines were completed and extended. The Station Masters house and the station buildings themselves sometimes had to be moved to the new rail terminus some miles away. Provisional school buildings were also relocated.

At the conclusion of unsuccessful Soldier Settlements, it was reported that farmers wishing to move away elsewhere could (if they could afford it) have their houses relocated. In Charters Towers in 1919, it was reported that 118 houses were moved to Townsville with a greater number expected in 1920 (Townville Daily Bulletin, 10th July 1920 page 7). As mines closed and work ceased, houses became ridiculously cheap.

How were houses moved

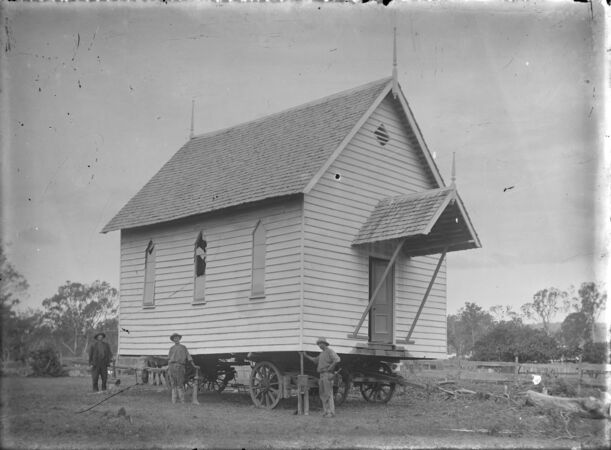

In the 19th century, buildings were mounted on bullock drays and moved very slowly.

Fred Gilliland transporting his house from Esk to Blackbutt by bullock team, 1924.

First the house had to be raised and supported on heavy wooden beams or steel supports so that the stumps could be removed and trucks or trailers positioned underneath the home, ready to make the journey. Earlier house removals used wheeled drays, similar to timber jinkers. Large homes and buildings could be divided into two or more parts to make the journey possible. Once in a new location, large wooden turning jacks (later hydraulic) were used to slowly position the home in the correct place. Finally, stumps were replaced and carpentry work to rejoin the parts of the building was undertaken. Smaller homes were moved as one building.

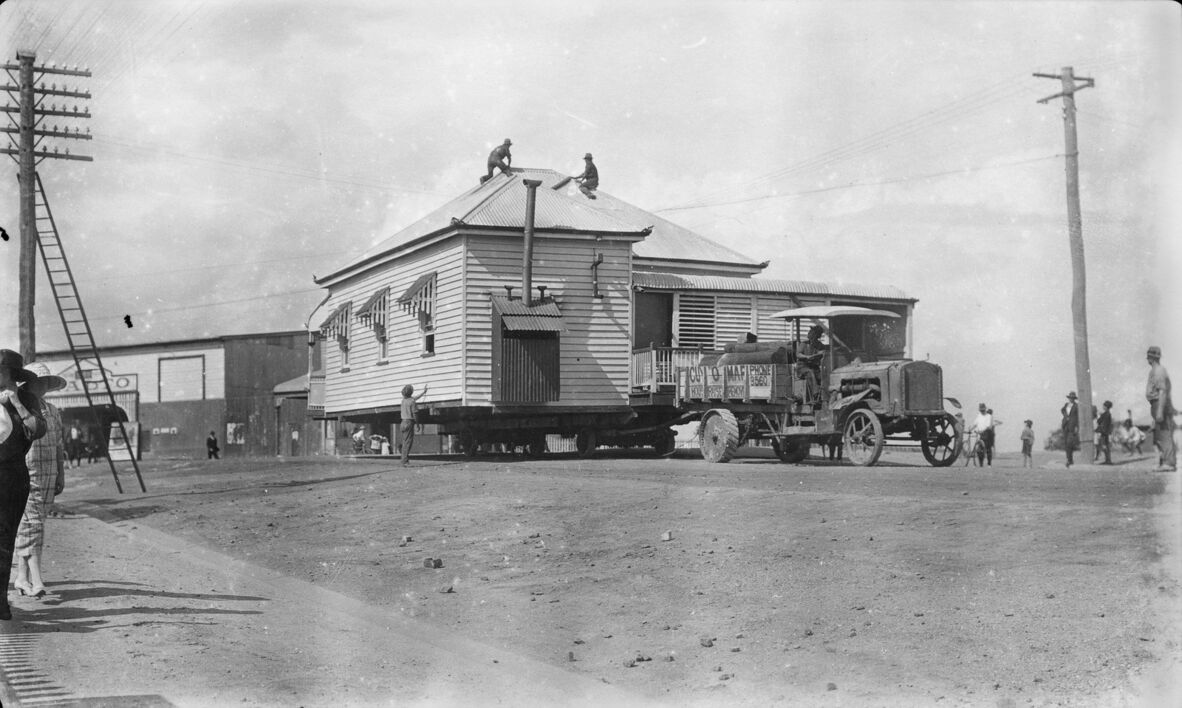

Corrugated iron worker's cottage is being relocated down Norman Street, Gordonvale, c.a. 1948. Nelson Park, Gordonvale is visible on right side of image. The building on the right was a bomb shelter in WWII. It was later converted to public toilets.

All manner of vehicles were used to move buildings. Photographs in the State Library collections illustrate that small houses were frequently pulled by tractors, trucks and even horse teams. Bullock teams (up to 64 bullocks or three teams working together) were used for very large houses and loads. However, on some occasions, the bullock team pulled the heavy house on a slide instead of on wheels where the landscape dictated it. A large wooden home could weigh up to 18 tonnes. In the 1920s, very powerful trucks such as the Renard Road Train engine were used to pull the large houses. In earlier years, moves were typically within three to five miles distance. However, as larger trucks became available as well as cranes and powerful hydraulic jacks to lift the house, the possible distances for removal became greater.

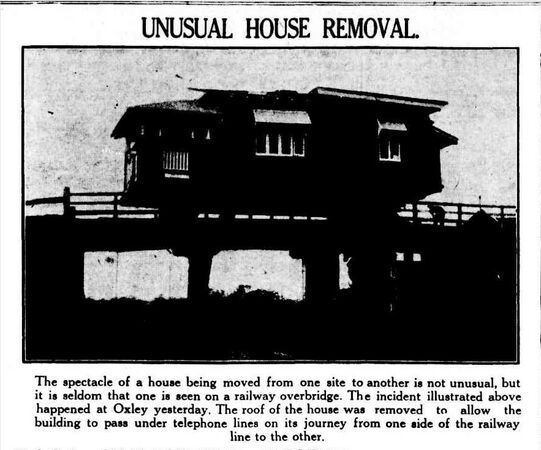

During the house move, at least one person was designated to lift electricity wires safely above the house. House removal photographs will often show a man perched high on the roof to enable safe crossings under wires. When crossing bridges, houses were raised to allow the wide load to travel above the wooden bridge railings.

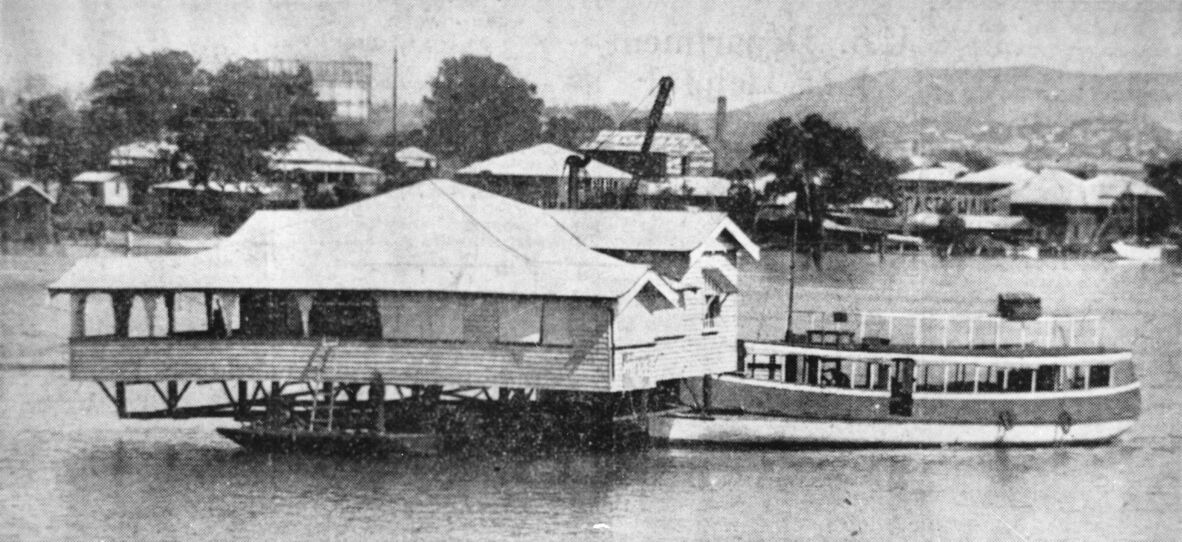

Barges and ferries were also used to relocate houses across rivers and streams, but also down river to the bay. Houses on the Moreton Bay islands were often taken by barge and then dragged into place by a truck or tractor.

This house was moved from Bulimba to Bishop Island in 1934 for Mr James Crouch The house is passing the Gasometer at Newstead with the pilot boat guiding the punt. The house was moved by Messrs McKenzie Bros who advertised themselves in 1934 and Brisbane’s Leading House movers. Courier Mail May 2nd 1934.

Houses were also moved around on blocks of land, to face a different street or to allow part of the land to be sold. However, after 1925 in Brisbane, it became more difficult to sell additional land beside a house as it had to be more than 24 perches, which was the new standard adopted by the Greater Brisbane City Council. Moving houses sideways involved 'sliding the house' or moving it very slowly, just an inch at a time using wooden jacks. This could take some weeks and the family lived in the house at night before more movement occurred the next day.

'Dunoon' being slid on blocks from the corner of Bayview Terrace and Drane Street to Drane Street.

In earlier times, buildings were often moved with the people inside. Pubs were moved to new locations and each night, wherever the building was located, the trading of liquor and food continued. It was hoped in the 1930s that houses would be able to be moved without any change to the routine of the residents.

Today, homes are still moved on trucks or semi-trailers, usually in the middle of the night to minimise traffic delays and with the support of flashing lights on ancillary vehicles to indicate the width required on the roadway. Due to safety concerns, occupiers are now not able to travel within the building when it is being removed.

Accidents and misfortune during house removals

City Council by-laws insisted that house removals be undertaken at night. Accidents and near misses were not seen by the public in daylight hours but they certainly did occur. In 1935, a house spun out of control down Constitution Road at Windsor and provided quite a spectacle jammed up against a light pole. Other houses lurched wildly sideways when the camber of the roadway changed. The worker on the roof, adjusting passing electricity wires was at times forced to leap off for safety. In 1949, in Proserpine, an accident of that nature broke both heels of the unfortunate worker.

Balonne Beacon, 22 August 1935, p 2

Finding when the house was moved, from which location to where, and when

For the house historian, finding out where a house had come from or where it was relocated is indeed a difficult task. Local councils and divisional boards were relatively disinterested in the house relocation business. If you were relocating a house to another location that was not within their jurisdiction, local authorities had little or no interest.

Family and neighbourhood memories

The best source of information regarding house removals usually comes from neighbours or family members. Older neighbours can often remember the spectacle of the house being removed or relocated. They may even remember where it was going to be relocated. Sometimes they will remember the sign of the removal company, which can be helpful hint. House removals were always a spectacle for local residents and many of the photographs of house removals show onlookers watching the event. It is therefore likely that someone in the neighbourhood will remember the removal.

A house on a wheeled trailer, being towed by a truck with the name Guyomar painted on the side. A group of men, including some with bicycles are standing on a street corner watching. Guyomar House Removals was owned by Frank Guyomar who passed the company on to Merv Alley who kept the company under the original name until the early 1970's.

Council building records

Shire or Council Building Records are not complete for building removals. Councils did not need to have the details of relocations and removals prior to 1920 and even after that date, some removals were not listed or noted. However, examples can be found in the records, so it is always worth looking for possible indications of the removal. Brisbane City Council building registers do list some removals. In 1945, a house owned by A Thorn of Yeerongpilly was moved to Chelmer. The contractor was A A Gaggin. The re-subdivision and portions are listed. Other Council records are stored at Queensland State Archives after some years. Otherwise, the records remain with the relevant council.

In Brisbane, the recording of building applications ceased in October 1945 and from November 1945 was replaced by a card system. Brisbane City Archives can provide advice on this index. Building approval cards 1945-1982 cover the years up until 1982 and may provide some helpful information. You can contact Brisbane City Archives for assistance accessing these records.

Church or organisation records

Church records may indicate removals within the parish or circuit, especially during the 1970s when the Methodist, Presbyterian and Congregational Churches amalgamated to become the Uniting Church. Church organisations sometimes sold houses on their property to make way for new buildings. Some were removed and others were demolished. Committee and business records of various church organisations under the umbrella of the Uniting Church are available in the John Oxley Library. Other church archives such as the Anglican Archives or the Catholic Diocesan Archives could also have useful information about when a building was removed from their property.

Newspapers

Newspapers offer a great array of information as they would advertise houses for removal. Usually, the advertisement would just specify the number of rooms and the building materials. For example, wood and iron or wood, iron and fibreboard or corrugated iron. Sometimes they would offer further information, such as ‘partly burned’ in the case of a house advertised for removal at East Brisbane in 1916.

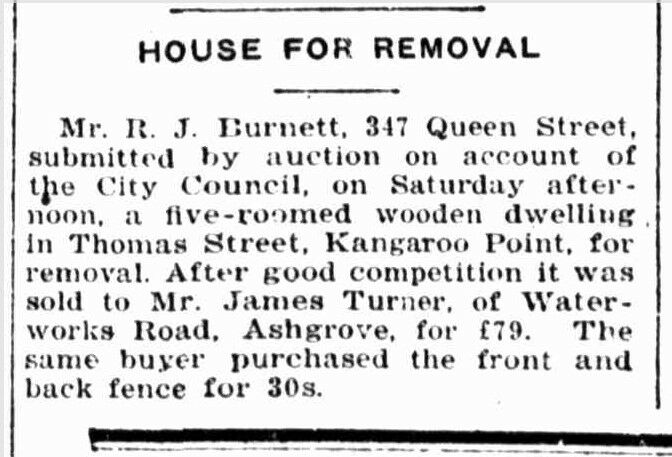

Many potential buyers would post requests for a house to buy in the weekend newspapers. There was a great desire to find a house that could be purchased cheaply. In 1925, this five room dwelling was sold for £79.

The Telegraph, 4 August 1925, p 4

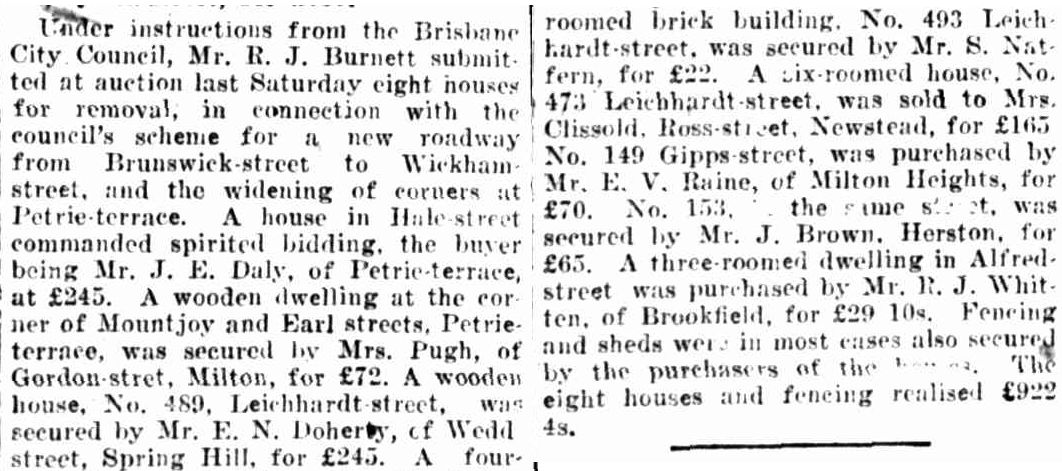

The Courier Mail, 28 June 1935, p 14

When searching in newspapers for house removals, use the heading of ‘Property Sales’ for descriptions of prices gained for properties including removal properties. Sometimes, it will also give you the name of the new owner, thereby allowing the researcher to find the house and its new location in post office directories or electoral rolls.

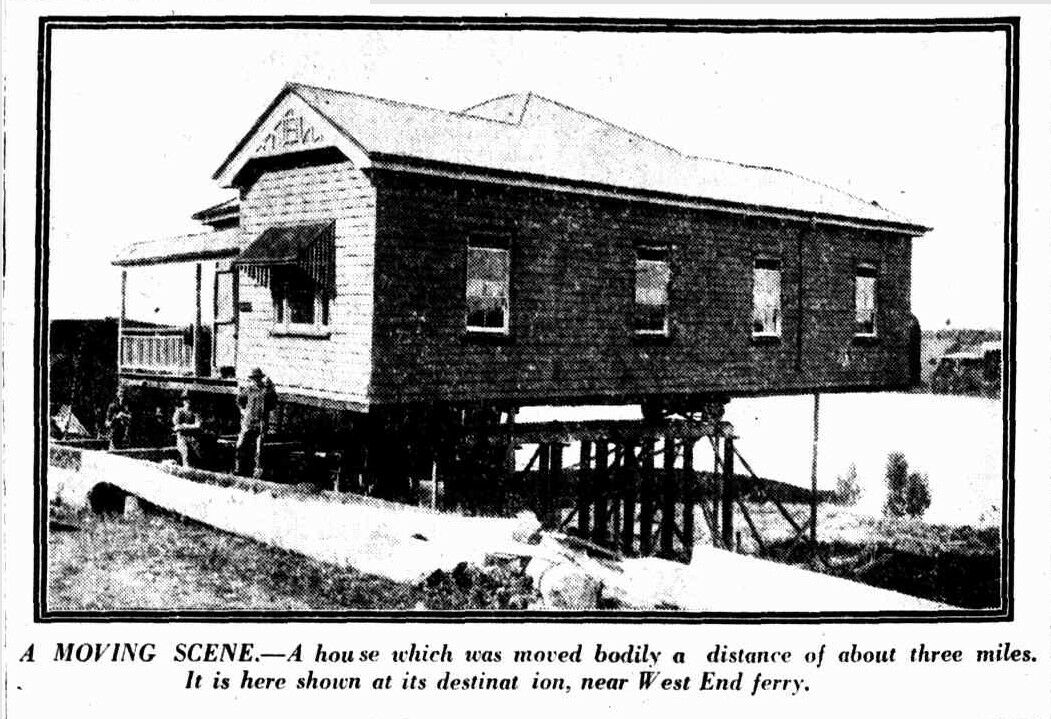

The Daily Mail, 14 July 1924, p 18

Electoral rolls and post office directories

These rolls and directories are useful if you have a name for the person who moved the house or purchased the house for removal – the relocation of that person to a new address will guide you to finding the house. Likewise, if you have an address from which the house has been removed, you will be able to see when the house was taken from its original location by an absence of that numbered building in the street.

Electoral rolls and post office directories for the twentieth century can be searched on Ancestry.com, available onsite at State Library. Post office directories only offer residential listings up until 1940.

Photographs of the house

Images of a house taken by a family may indicate where your house was located prior to removal. This image shows the Brisbane River in the background.

The Daily Mail, 14 July 1924, p 18 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217596891

Now a riverfront home, it was probably moved from an inner South Brisbane or a Woolloongabba street. Sometimes other landmarks (for example a Foresters hall, a Butchers Shop or hotel) can be seen in the background or beside the house prior to removal or after relocation. Such photographs can therefore provide clues when searching for the history of that house.

House removal companies and records

Every major city in Queensland had companies that specialised in house removals. In Brisbane, there were a number like the McKenzie Brothers, Guyomar Removals, the Soden family, and in more recent times, Mackay Brothers, Queensland House Removals and the Wright House Removers among others. There are also demolition companies in major cities. Telephone or post office directories for the era will list the companies involved in this business.

In the case of more recent removals, it may be worth contacting the house removal company in the area in case they have records. Where older companies were involved, it is more difficult to trace the removal.

Examples of houses that moved

Yardley Avenue Ashgrove Working Class Cottage.

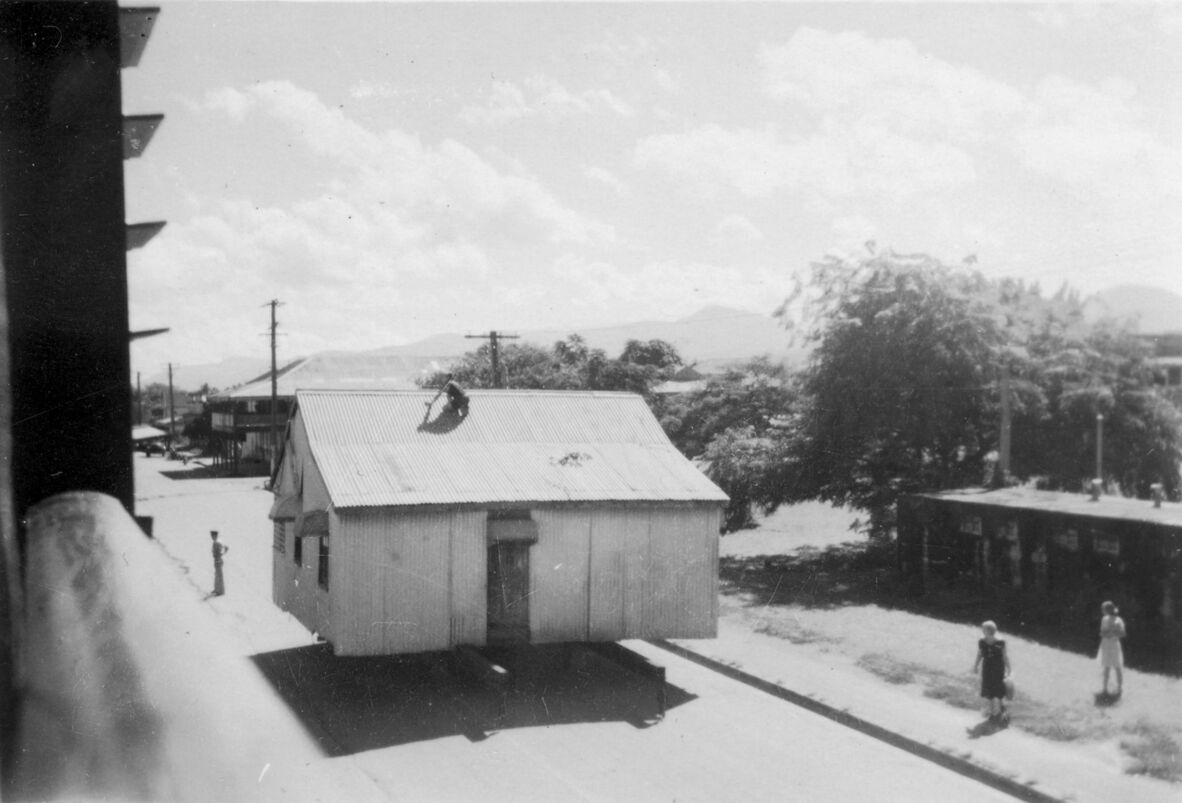

7 Yardley Avenue, Ashgrove was moved onto this block of land in 1917. It was purchased from Fortitude Valley when road widening was required in Wickham Street. The money for the land was obtained through a building society called the Bowkett Number 1 Society. The land was purchased in Graham Road off what was then known as Three Mile Scrub Road (now Ashgrove Avenue) at Ashgrove. At the time, it was very much outer suburban land. In later years, the street was renamed Robert Street and finally Yardley Avenue. Later, larger ‘Ashgrovian homes’ were built around this small home which has all the style indications of having been built in the late 1860s or 1870s.

The house was purchased in 1916 or 1917 for less than £60. Removal costs would then have been added to the total expenditure. However, this small house was moved twice. The home was moved first from Fortitude Valley to Ashgrove and then again onto the left-hand side of the block in Ashgrove in the 1930s to allow the land next door to be sold. However, the land size did not quite reach the required 24 perches, and many years elapsed until the side block was able to be sold. Now, a modern home has been built on the remaining block. This Queenslander cottage of two bedrooms became the home of six children and their parents and is still standing on the site where it was relocated more than one hundred years later. It is now at least 150 years old.

Information supplied by Christina Ealing-Godbold from family knowledge.

Peppermint Cottage Macleay Island. Moved from Railway Terrace, Milton in Brisbane.

Peppermint Cottage at MacLeay Island 2024. Note the corrugated iron on the side of the cottage to replace previously removed timber

The house now located on Macleay Island and known as ‘Peppermint Cottage’ is a Queenslander with an asymmetrical pyramid roof and projecting front room located on the right side when viewed from the street. The drop from the apex of the roof and window hood suggests a cottage built around 1910.

The house that was moved to Macleay Island may have been either of two identical asymmetrical pyramid roof cottages located just before the cross street with Railway Terrace, Crombie Street. These can be seen on the Brisbane City Council Detail plan, below.

Brisbane City Archives Detail Plan no 844.

Most of this area, including the Milton Estate, was carved up and built upon between 1888 and 1910. It would have been heavily impacted by the floods of 1890, 1893 and 1931 and this may account for a continually shifting population. It was very much a working class population, with labourers and tradesmen predominating and a considerable number of rented properties.

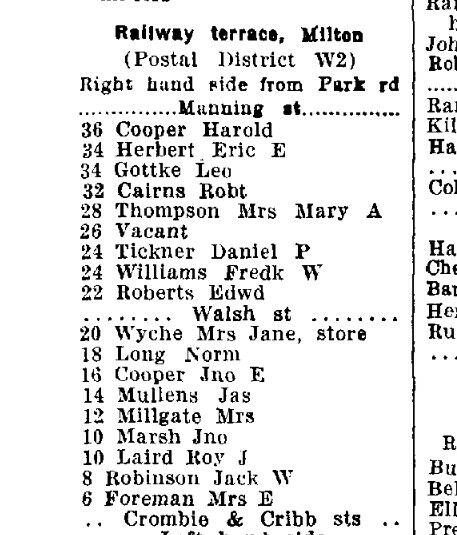

The post office directory from 1938 shows a Mrs E. Foreman at number six. As can be seen in the detail plan the house at number 6 had a side wall onto Crombie Street, and it may have been attached to a side fence. Number six Railway Terrace is very likely the cottage that was moved to Macleay Island which has corrugated iron infill along one side of the building.

Queensland Post Office Directories, 1938 showing Railway Terrace, Milton

For many years, number 6 Railway Terrace Milton was the home of Mrs Edith Foreman. Mrs Foreman lost her husband, a farmer in Redland Bay, in 1923. After this event, she appears in Railway Terrace. However, by the 1940s she has moved again, to Ashgrove. The cottage was owned subsequently by Catherine Mary Falvey who died in 1953. She resided with her son in law and daughter and family - Gordon Brockfield and Mary Josephine Brockfield. Mary inherited the house upon her mother's death. The Brockfield family lived there for many years before moving to The Gap. The house was moved to Macleay Island after 1980.

Peppermint Cottage arrives on Macleay Island on the back of a truck, transported by ferry.

Photograph courtesy of Sandra Scott, and Christine Martinez.

Tracing the story of the Queensland house can include having to search for the building in a new location. This is a challenging task that requires some knowledge of either where the house was located originally, the family who may have moved it or its new location. State Library of Queensland has a range of indexes, databases, photographs, maps and suburb or town histories that can be used to investigate the probable initial location and subsequent relocation of a Queenslander House.

Selected resources

Books

The Queensland House : a report into the nature and evolution of significant aspects of domestic architecture in Queensland / Donald Watson.

The Queensland house : a roof over our heads / editors Rod Fisher, Brian Crozier

Looking after the Queensland house / Heritage Unit, Brisbane City Council

Abode of our dreaming : place, climate, culture and dwelling / James C Woolley

The house in Queensland : from first settlement to 1985 / by Peter E. Newell

Journal articles

OLD HOUSE, NEW PLACE: The lowdown on relocated homes. Madeleine De Gabriele. Sanctuary: Modern Green Homes, No. 57 (SUMMER 2021), pp. 54-59

Perspectives on built heritage preservation: a study of Queenslander homeowners in Brisbane, Australia. Vanessa Neilsen, Dorina Pojani. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, Vol. 35, No. 4 (December 2020), pp. 1055-1077

Journals

Home builders annual. Brisbane : Penrod Publications; 1938 – 1953

Photographs

Photographs of House Removals. John Oxley Library, State Library of Qld

More Information

Plan your visit – https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/visit

What’s on at State Library – https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/whats-on

Library membership – https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/services/membership

One Search catalogue – https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au

Ask a librarian - https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/services/ask-librarian

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.