Hidden Enemies: Submarines and Subversive Witches

By Ethan Devereux-Phillips | 31 October 2023

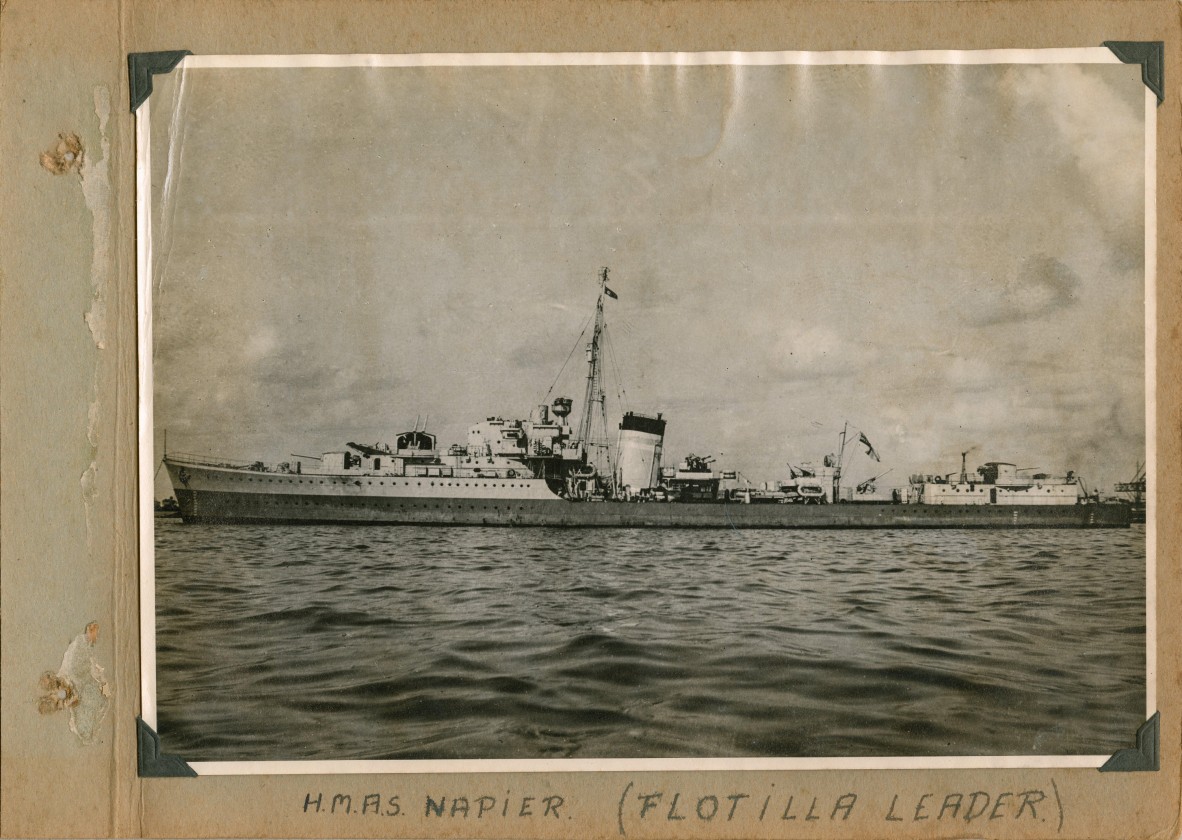

The date is the 25th of November 1941. The weather is clear and the Mediterranean Sea calm, bar where it breaks upon the bows of the Royal Navy’s 1st Battle Squadron. His Majesties Ships Barham, Warspite and Valiant – all Queen Elizabeth class battleships and veterans of the last war – are steaming home to the British naval base at Alexandria. Screening them are nine destroyers, including the Australian HMAS Napier. One of five N-class destroyers lent to the Royal Australian Navy during the war, Napier has already seen heavy action during the evacuation of Crete, resupply of Tobruk, and convoy and harbour protection.

HMAS Napier (Thomas Colin Low Photograph Album, 1940-1945, Low, T.C., State Library of Queensland.)

Aboard Napier is Ordinary Seaman Thomas Collin Low, a man handy with a camera. Born in Brisbane in 1921, Thomas has served in the Naval Reserves prior to being called up in 1941. Having only being posted to Napier on the 3rd of November after training at Cerberus, this escort is likely among his first wartime operations. It is to be a dramatic introduction.

Able Seaman Thomas Colin Low in uniform (Thomas Colin Low Photograph Album, 1940-1945, Low, T.C., State Library of Queensland.)

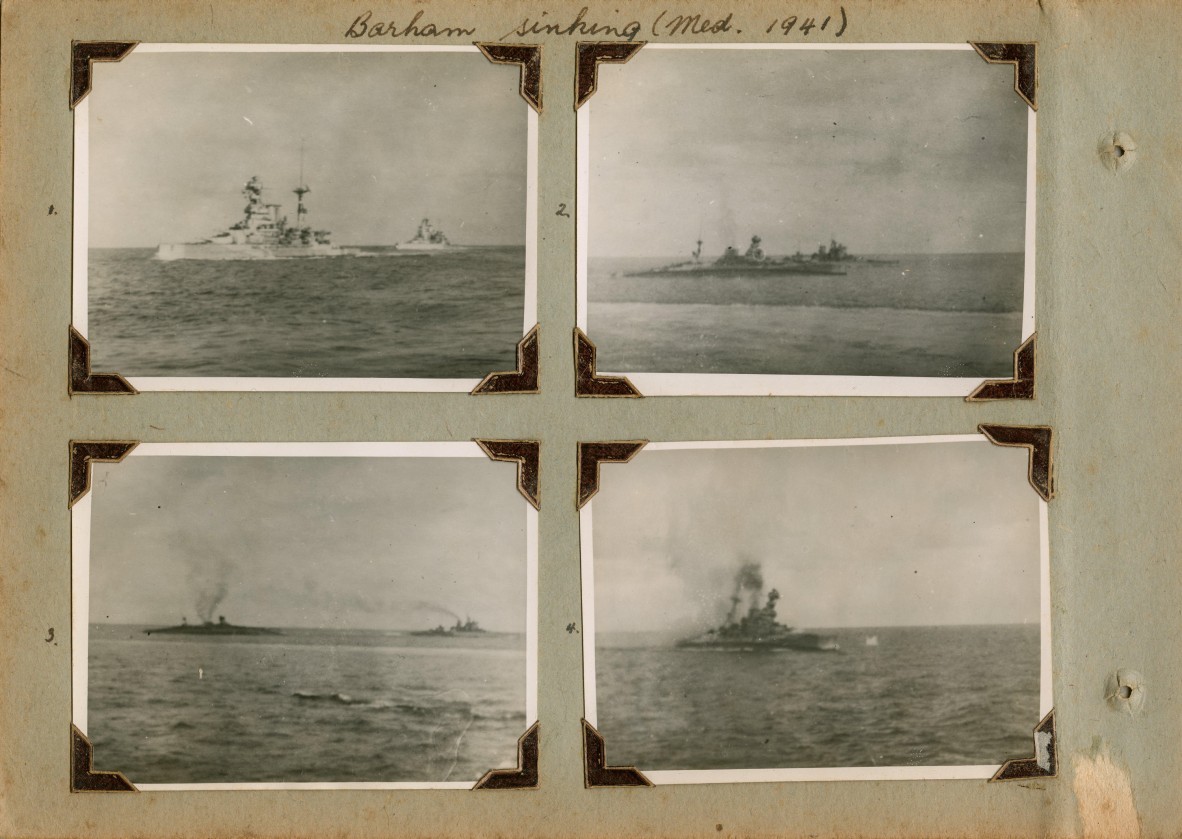

Enemy aircraft have been shadowing the force all day, but none have attempted an attack. By and large, the day has been uneventful until now, a little past 4pm, when three massive columns of water erupt on the portside of Barham – Torpedoes. Hit amidships, just abaft the funnel, all electric power is lost, although Barham continues to surge ahead at 20 knots. Water streams into the hull, causing Barham to list to port with developing intensity. It is clearly time to abandon ship – every man for himself.

Astern of Barham, Valiant turns hard to port to avoid the stricken ship. As she does, a new vessel emerges from beneath the waves about 150 yards off Valiant’s bow: the periscope and conning tower of German submarine U-331. Likely forced to the surface by firing all bow tubes at once, the submarine quickly comes under fire from one of Valient’s “pom-pom” anti-aircraft guns. Despite the vigilance of the gunners, they are unable to damage the submarine before it crash-dives and makes its escape.

The battleship HMS Barham begins to sink after being hit by three torpedoes (Thomas Colin Low Photograph Album, 1940-1945, Low, T.C., State Library of Queensland.)

Back aboard Napier, Thomas Low is on deck with his camera at the ready. Napier had been steaming close to Barham when the torpedoes struck, and Thomas has a clear view of the tragedy as it unfolds. Sailors scramble over the side of Barham, taking care to avoid the sharp barnacles as the underside of the hull exposes itself to the sky. There is little time to launch many Carly floats, let alone the larger tenders. Men jump into the sea with little life support. Through his camera lens, Thomas witnesses the ship keel over with a terrific smack. Seconds later, a massive explosion tears through Barham, obscuring her in dark smoke and launching debris into the air. Between the torpedo strikes and the detonation of the aft 15-inch magazine, just four minutes have elapsed.

As the pall of smoke disperses, Barham is no more. She is bound for her final resting place afast on the ocean bed, taking with her 862 crew. Those who survived are left clinging desperately to floating refuse amongst an oil-slicked sea, anxiously awaiting rescue. The destroyers HMS Hotspur and HMAS Nizam are quickly on station to assist, but it takes hours before everyone is safely loaded into whalers and taken onboard. The survivors are bound for Alexendria for further medical care and much needed recuperation. As for Thomas Low, he shall continue to serve aboard Napier for the duration of the war in the Mediterranean, Atlantic and Pacific before being discharged in January 1946, photographing his experience all the way.

HMS Barham lists over, explodes and sinks (Thomas Colin Low Photograph Album, 1940-1945, Low, T.C., State Library of Queensland.)

The loss of Barham was kept secret for two months for intelligence security, as the Germans were initially unable to confirm which ship had been torpedoed and whether it had sunk. The immediate family of the deceased were alerted, but otherwise it was hush-hush lest loose lips confirm sunken ships. Yet, news was to break to the public in a most peculiar way – through the work of Scottish spiritual medium Helen Duncan. Renowned for an ability to produce ectoplasm during séances, Helen Duncan had made a living as a medium with an office in Portsmouth, the “Master Temple Psychic Centre.” In the tragedy and uncertainty of war, many Brits sought answers to the fates of their loved ones and Helen’s skills were in high demand. She charged a pretty penny for the service too, earning £100 a week or more from group séances and private visitations. It was during one such séance, shortly after the sinking of Barham, that Helen supposedly contacted the spirit of a sailor who had perished aboard. When word of the event reached the admiralty, they were gravely concerned.

A security risk was a deadly liability in wartime Britain, regardless of whether it was obtained through espionage or spiritual contact. So it was that in January 1944, Helen Duncan was arrested during another séance in Portsmouth. The pivotal invasion of Normandy and liberation of Europe was rapidly approaching, and Military authorities could ill-afford the possibility of another leak. Initially, the warrant for Mrs Duncan’s arrest had been issued under the Vagrancy Act with an accusation she was defrauding the public. It was not the first time she had faced such a charge, being found guilty of fraud in Edinburgh in 1933 and fined £10 when a supposed materialisation of the child “Peggy” was found to be a manipulated women’s stockinette undervest. The powers that be, however, were concerned about far graver matters than ghostly underwear. They wanted Mrs Duncan behind bars where she would be unable to spread any information and they turned to another piece of legislation to do it: the 1735 Witchcraft Act. Whereas previous legislation had labelled witches and magicians as heretics who consorted with daemons, the 1735 Act reframed them as fraudulent con artists and vagrants who could see jail-time for their crimes. Notably, the 1735 Act was also the basis for Queensland’s own anti-witchcraft laws under Section 432 of the Criminal Practice Rules, 1900.

Queensland papers report on the trial of Helen Duncan (Left: Mediums' "Spirits" Dashed (1944, April 2). Sunday Mail (Brisbane, Qld. : 1926 - 1954), p. 1. Top right: Court Entered Into Spirit Of The Thing (1944, April 17). The Evening Advocate (Innisfail, Qld. : 1941 - 1954), p. 2. Bottom right: TRIAL FOR WITCHCRAFT (1944, April 5). Daily Mercury (Mackay, Qld. : 1906 - 1954), p. 6.)

The trial of Helen Duncan made news in Queensland, where details were published in Warwick’s Daily Mercury, Innisfail’s The Evening Advocate, and Brisbane’s Courier Mail, Telegraph and Sunday Mail. In Britain, the trial was a public farce with spiritualists and believers advocating Mrs Duncan’s legitimacy on one side and other spiritualists and witnesses claiming she was a fraud on the other. In the end, a guilty verdict was passed and Mrs Duncan was sentenced to nine months incarceration. Three compatriots were also found guilty, one of whom, another woman, received a four-month prison sentence. The military officials got what they wanted – no more security leaks were forthcoming from Mrs Duncan. However, the uproar caused by the case prompted a change of legislation and the Witchcraft Act was replaced by the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951. Helen Duncan was among the last people in Britain (and most of the Commonwealth) to be tried as a “witch.” Although no one has received a recorded conviction of witchcraft in Australia, Queensland’s own anti-witchcraft laws were not omitted from the Criminal Code until 2000.

References and Further Reading

“Court Entered into Spirit of the Thing,” 1944, The Evening Advocate, 17 April, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article212429380.

“From the Vault – Exercising Witchcraft or Telling Fortunes,” 2018, Queensland Police Service, https://mypolice.qld.gov.au/museum/2018/11/13/vault-exercising-witchcraft-telling-fortunes/.

“Helen Duncan, Scotland’s Last Witch,” n.d., Johnson, B., Historic UK, https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofScotland/Helen-Duncan-Scotlands-last-witch/.

“HMS Barham – Survivors Account Of Sinking,” 1991, McDonald, I.H., Naval Historical Society of Australia, https://navyhistory.au/hms-barham-survivors-account-of-sinking/.

“Medium’s “Spirits” Dashed,” 1944, The Sunday Mail, 2 April, p. 1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article97945816.

“Prison Sentence Rocks Spiritual Medium,” 1944, The Scone Advocate, 6 April, p. 1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161121821.

“The HMS Barham Association Website,” 2008, HMS Barham Association, http://www.hmsbarham.com/index.php.

“Trial for Witchcraft,” 1944, Daily Mercury, 5 April, p. 6, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article170850610.

“WHICH WITCH(CRAFT ACT) IS WHICH?,” 2020, Hartland, N., UK Parliament, https://archives.blog.parliament.uk/2020/10/28/which-witchcraft-act-is-which/.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.