Guest blogger: Mark Clayton.

Having escaped the combined grant-funded attentions of historians, archivists, librarians, conservators, academics and curators, Queensland’s (and Australia’s) first Great War trophy faces the prospect of another one hundred years of service as a garden ornament.

German field guns captured during the Battle of Loos in the square at Bethune, 28th September 1915. Imperial War Museum, Q28963. Australia’s first Great War trophy may well have been among this lineup.

During and immediately after the 1914 - 1918 war thousands of captured enemy cannons, mortars, machine guns, aeroplanes and vehicles were returned to Australia and distributed to towns and cities throughout as war trophies. Prominent amongst this largesse was the armoured vehicle Mephisto which, after having been abandoned by the Germans and salvaged by the British, was diverted to Brisbane following direct representations by Queensland’s wartime Premier T.J. Ryan. This darling of the war trophies will shortly reappear as the centrepiece of a $14 million, four-year-long exhibition redevelopment at the Queensland Museum.

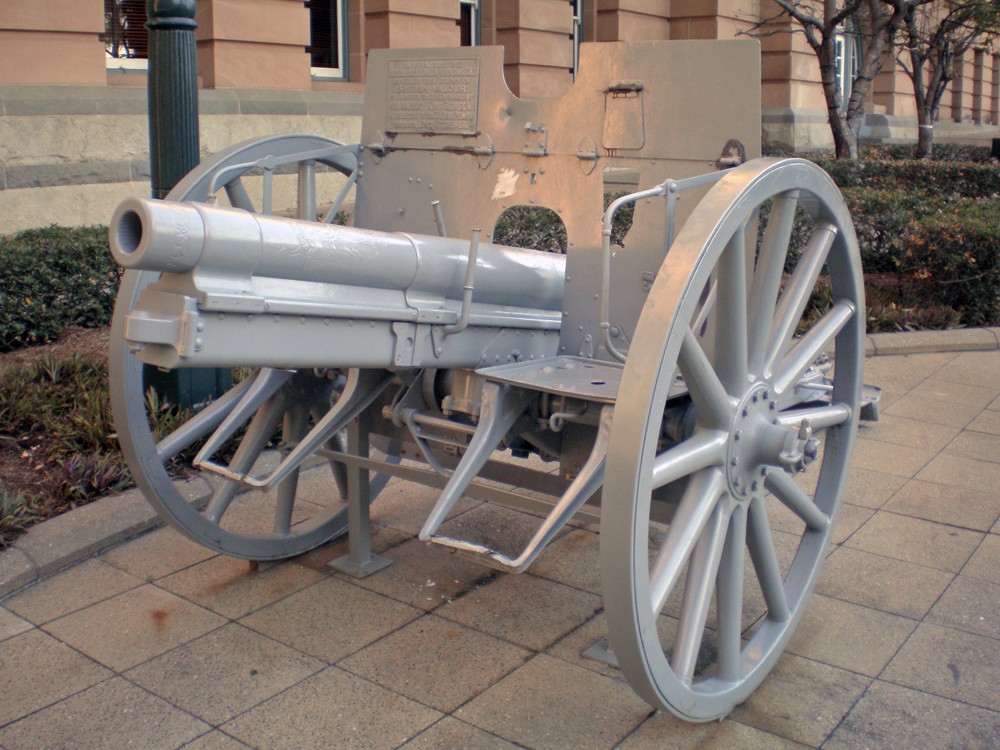

Meanwhile, in Queen’s Park on the opposite side of the river there stands - exposed to the elements - a lone German 77mm field gun, also delivered to the capital in 1916 as a direct consequence of Premier Ryan's personal representations to Lord Kitchener. Unlike the armoured vehicle Mephisto (which was developed too late, and in too few numbers to influence the war’s outcome), this FK96 n.A. is the defining technology from an industrialized war that was ultimately reduced to a contest between duelling artillery. Made by Fried Krupp, the world’s leading armaments manufacturer at that time, its barrel is elaborately adorned with the double-headed eagle of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

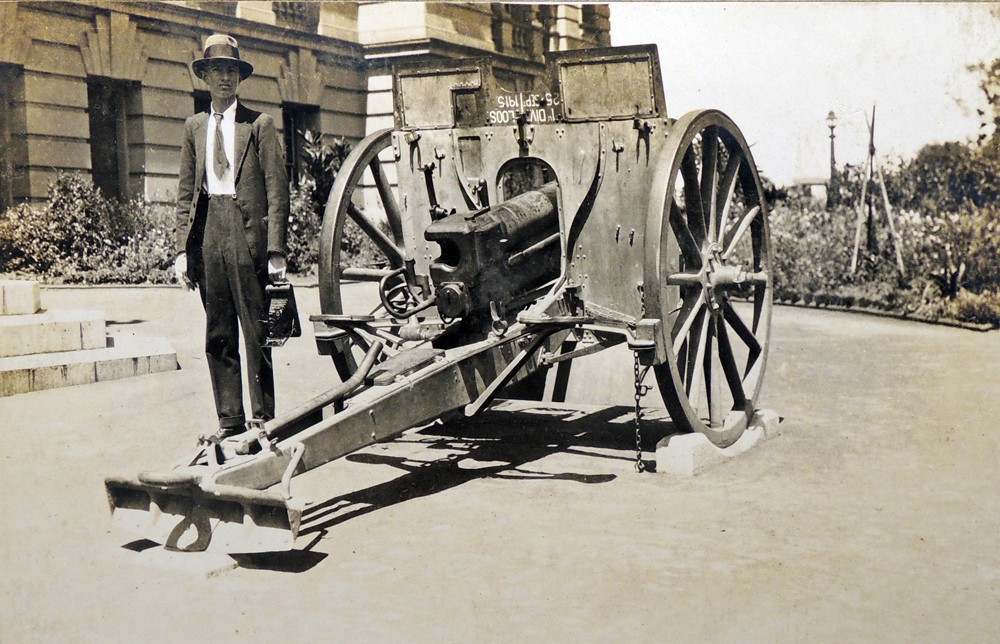

Taken in 1919, the inverted shield inscription reads…’Captured by the 1st Division, Loos, 28th September 1915’. Queensland Museum, Henry Olsen Album, 1919, H9970

Seemingly camouflaged by its occasional coating of Dulux high-gloss enamel (grey, of course), a plaque riveted to the its shield describes it simply as ‘a trophy to British valour’. In this respect it is also unique, since every other trophy gun in the country testifies to Australian prowess, sacrifice or gallantry.

Voluntary enlistments had begun free-falling in Australia following the disastrous 1915 Gallipoli Campaign and although Ryan was a staunch anti-conscriptionist he nonetheless remained committed to supporting the war effort, preferring to try and arrest this decline by stimulating volunteering.

German guns had begun arriving in England as early as 1915, when captured artillery from Loos (France) were being proudly presented to lord mayors and councillors across the country, ‘as a sign, perhaps, that the enemy was emasculated, and that victory was within reach.’

Ryan understood that ‘enemy weaponry was the perfect focus for fundraising and patriotic calls-to-arms. The war waged in Flanders Field had also to be fought in the hearts and minds of the folk back home, and a reminder of what the allied troops were facing helped the cause.’ A few months prior to his departure for England in early 1916, Australian newspapers had reported the mass display in London of twenty-two German guns captured during ‘the glorious day at Loos’ (when in fact the British forces were defeated, suffering 59,247 casualties).

At the gun’s formal handover on 18th August 1917 Queensland's Governor bravely speculated that ‘Perhaps the day might come when it would be desirable to let bygones be bygones and to return the gun. (A Voice: "Never.") That would be for the people of Queensland to decide.’ Quote and image from A History of Queensland by Raymond Evans, p.158

We don’t know if Ryan also saw this exhibition, but we do know he wasted no time in applying directly to Lord Kitchener for one of the Loos trophies to be sent to Australia (or, more precisely, Queensland). The British at that time hadn’t even established their own War Trophies Committee and it wasn’t until much later again, that the Australian War Trophies Committee was formed.

Ryan’s initiative was rewarded when Kitchener advised his Secretary of State for the Colonies, in a letter dated 30th May 1916, that he was ‘making arrangements for a captured German gun to be handed over for despatch to the Premier of Queensland’, adding that ‘It is doubtful whether we shall be able to meet similar demands from the other portion of our Dominions, so I hope It will not be taken guide as a precedent.’

Securing the nation’s first war trophy must have been especially satisfying for Ryan given the parlous relationship that existed then between himself and the Australian Prime Minister, Billy Hughes. Rather than trumpet his success however Ryan chose instead to bide his time, deliberating delaying the gun’s formal handover another fifteen months until the likelihood of a second conscription referendum seemed certain.

Not surprisingly media accounts of the ceremony, which took place four months before the referendum one Saturday in late August 1917, represented the Queensland Premier as an enthusiastic supporter of the war effort whose influence extended well beyond these shores...

Lunch hour at Queen's Park, Brisbane, 1949 . John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Neg. 94595

‘He (Mr. Ryan) happened to be in London,and he asked the secretary of State (Mr. Bonar Law) for some trophy as an incentive to the people of Queensland. Later he saw Lord Kitchener at a banquet In connection with the Russian Duma, and spoke to him. A few days afterwards he received a letter signed by Lord Kitchener - one of the last written by that great soldier - In which arrangements were made for the gun to be handed over to the people of Queensland (Applause).’

State Governor Sir Hamilton J. Goold-Adams added to this already favourable impression by noting that ‘The event was absolutely unique in the history of the Empire, as he believed that this was the first occasion on which the Motherland had handed over oflicîally any trophy taken in any war of the British.Empire.’

The occasion concluded with Mr. F. MacDonnell (ex-recruiting sergeant) taking ‘advantage of the opportunity to deliver a forceful appeal to eligible men to enlist.’

Much more than just a war trophy, the Queen’s Park gun had become a pawn in a high stakes political contest in which Ryan, as leader of the second anti-conscription plebiscite forces, ultimately prevailed (despite being the only Australian Premier opposing the ballot). The country was flooded with almost 7,000 war trophies in subsequent years and yet none of those that followed, it seems, were ever used for such blatant political ends.

In 1937 The Queenslander Annual described Queen’s Park as ‘An emerald setting liberally studded with multi-coloured flowers, Nature’s glowing gems (1st November 1937, p.38)’. In the foreground is the state’s first Boer War trophy, and behind it stands Australia’s first Great War trophy. The Courier Mail described the former as Victorian junk when, in March 1948, it was removed to the Queensland Museum.

The public’s interest in war trophies faded quickly in the years following the Armistice with some municipalities (notably Brisbane, Maryborough and Toowoomba) eventually displaying undisguised disdain for these bellicose reminders. Nowhere was this shift in attitude more evident, than here in Brisbane where the City Council’s Parks Superintendent, Harry Oakman, orchestrated a sixteen-year-long purge against all things martial. He had no sooner been appointed by Brisbane City Council, in 1946, when he set about systematically removing and disposing of every item of obsolete artillery, from every public space, within his sphere of influence. As a consequence, scores of colonial, Crimean, Boer, Great and Second World War guns were removed from the city’s public spaces and corralled into Council’s Crosby Park Depot pending their burial, sale, or gifting (to recipients beyond the city’s boundaries).

The city’s two most prominent war trophies (viz. the German behemoth Mephisto, and the Queen’s Park FK96) somehow survived this purge perhaps because, unlike Brisbane’s other war trophies, these alone had been secured by the State Premier (a factor that may have imbued them with some added protection). Queensland Museum had tried again in late 1946 to get rid of ‘the ugly object across the entrance to the museum’ (viz. Mephisto), a move that was later quashed by the State Premier’s intervention.

Looking resplendent with its latest coating of Dulux high-gloss Weathershield, Queensland's first Great War trophy is the only one that pays homage to British Valour. Image: Mark Clayton

We’ve probably all walked past the Queens Park FK96 dozens of times, without ever really noticing it. For a century now this silent sentinel has stood guard over the city’s lunchtime office workers, its permanence and prominence rendering it invisible to both their gaze, and their attentions. It is difficult though to imagine another Great War relic that can speak to us more authoritatively or forcefully about that conflict’s dominant themes...Empire loyalty and disloyalty, socialism, propaganda, conscription, recruitment, triumphalism, military commemoration, technology, military strategy, Federalism and so on. In every respect too this is the nearest thing to an ideal museum artefact, being: substantially intact; comprehensively documented; impeccably provenanced; and capable of simultaneously addressing important historical and contemporary themes of both local and international significance.

Was this civic ornament too well camouflaged, perhaps?

For a fuller account of this episode see this writer’s article, 'Seeds of Discontent', Queensland History Journal, Vol.23 No.9, May 2018, pp. 563 - 580.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.