Jan Davis, Siganto Foundation Creative Fellow shares with us her journey in developing One thing becomes another.

I am in the second phase, the experimental phase of One thing becomes another, my three-stage project to examine diaries and farm records from the John Oxley Library collection and transfigure them as artist’s books. I’ve read many original records, examined the manner of their presentation and reflected on the labouring lives of the men and women recorded there. In my studio I have been exploring how I might best represent their labour, their actions on and in the landscape. It has been a period of intense activity, my labour mirroring the labour of those other lives.

Certain dilemmas had been gnawing away at me from early in the project and needed to be resolved in the studio. Firstly, I had no connection to the places about which I was reading and planning to make a book. This was troubling because so much of my work is driven by a need to articulate my relationship to a particular place. Secondly, the records of labour are written by Europeans who had displaced Indigenous Australians. How could I appropriately acknowledge the labour of the First Australians? And finally, labour relations (between employers and employees) in Queensland were fraught from the very early days of European settlement. The process of resolving these matters has been one of drawing, erasing and drawing again.

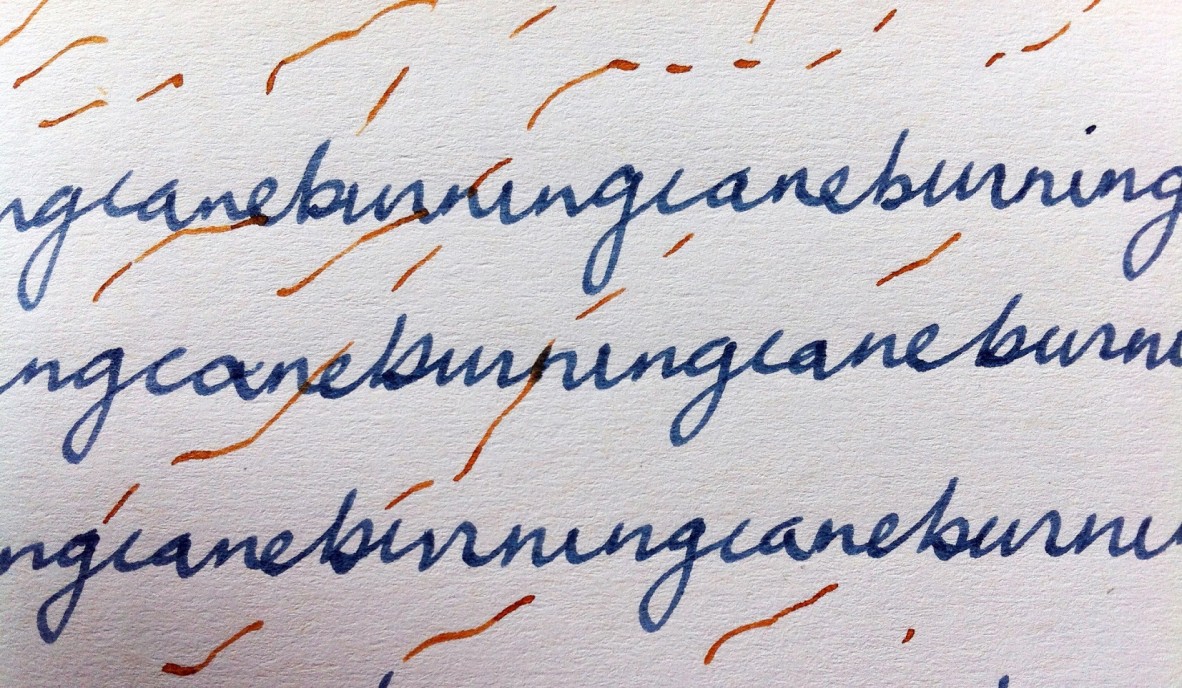

The answer to my first dilemma gave significant direction to my project. I resolved to think of my project as not about Queensland as a geographical site, but rather to treat the State Library of Queensland and its archive as the site of my exploration. I stopped asking myself about the location of particular activities and began to collage my material seamlessly together as a larger fabric with a shape unrelated to geography. I drew greater direction from the materiality of the archive, the papers, the handwriting, the enclosures. My focus returned to the record-keeping and to the act of writing itself. I acquired a set of dip-pen nibs and taught myself to use them. I resolved that my book(s) would be fashioned like a diary and enclosed in a box like those located in the the State Library of Queensland repository. I made decisions about drawing and writing materials, about paper and about page dimensions and format, all of which will be revealed in a later blog that focuses on the production of the books.

In pursuit of an answer to my second dilemma, I searched the records for reference to Aboriginal labourers but found in many instances that their presence was implied rather than explicitly identified, for example in ‘Frank and hands mustered’ or as ‘housemaid’ in a wages book where no wages, but rations only were listed. I resolved to represent the labour or activity of the First Australians by drawing on certain artifacts that are held in the Queensland Museum collection. Items such as grindstones or woven bags record labour both through their fabrication and through their documented function. In my artist’s books I will supplement this evidence with the recorded observations of settlers and explorers who saw the outcome of Aboriginal labour, whether it was seed caches, nets, or freshly burned swathes of country.

After reflection on the fraught labour relations in Queensland I realised they were sufficiently complex to be a life’s work in themselves and I resolved that they will, by necessity, play only a discreet role in my artist’s books.

The design of my books, the influence of artists Bea Maddock and Hanne Darboven, and my interaction with master bookbinder Fred Pohlman will be discussed in my next and final blog.

Jan Davis 30th March 2015

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.