Dr Lilian Cooper and Josephine Bedford: A year with the Serbian Field Hospital

By Alaine Baldwin, Engagement Officer, Anzac Square Memorial Galleries | 11 March 2025

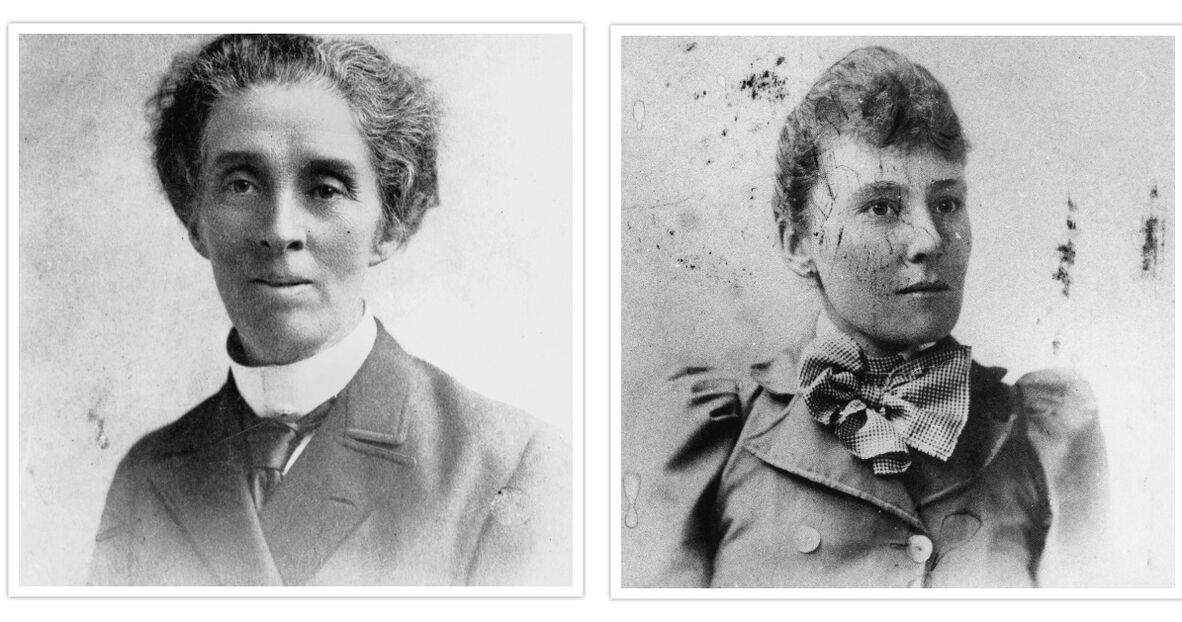

Much has been written about the remarkable couple Dr Lilian Cooper and Josephine Bedford and what they accomplished in Brisbane after they migrated from England in 1891. Both these women played a prominent role in the growth of Brisbane and Queensland and the role of women in its development, including Lilian trailblazing her way as the first female doctor registered in Queensland and Josephine establishing the Creche and Kindergarten (C&K) Association. However, in 1916 they left Brisbane for a year to support the war effort in Europe by working with the Scottish Women’s Hospital (SWH).

Lilian is generally described as ‘a tall, angular, brusque, energetic woman’ known to be very forthright and prone to swear and smoke. However, she was also meticulous and in the operating theatre displayed a skill and swiftness of movement which, combined with her calmness under pressure and amazing work ethic, contributed to her success as a battlefield surgeon. Josephine on the other hand was referred to as a kind, gentle person, ‘a perfect dear’ who possessed a remarkable capacity for organisation and perseverance, both necessary skills when she was made the motor transport officer and put in charge of the female ambulance drivers attached to the field hospital where Lilian worked.

Portrait of Dr Lilian Violet Cooper and Miss Josephine Bedford.

At the outbreak of the war both Lilian and Josephine, aged 55, offered their services to the military authorities in Australia but were rejected due to ‘the disability of sex’. Fortunately, their suffragist leanings meant they were never going to ‘stay home and knit socks’. Scottish suffragist Dr Elsie Inglis had a similar experience when she offered her services to the British Army and suggested sending women’s medical units to the Western Front. In fact, an official responded to her offers with, ‘My good lady, go home and sit still’. Unsurprisingly, this did not happen, and Elsie instead founded the Scottish Women’s Hospital (SWH) and put her readymade, all female medical units to use. Over 1300 women (doctors, nurses, laboratory technicians, x-ray operators, orderlies, administrators, drivers, cooks etc.) served in her 14 medical units throughout the war in France, Russia, Greece, Corsica, Malta, Romania, Salonika and Serbia.

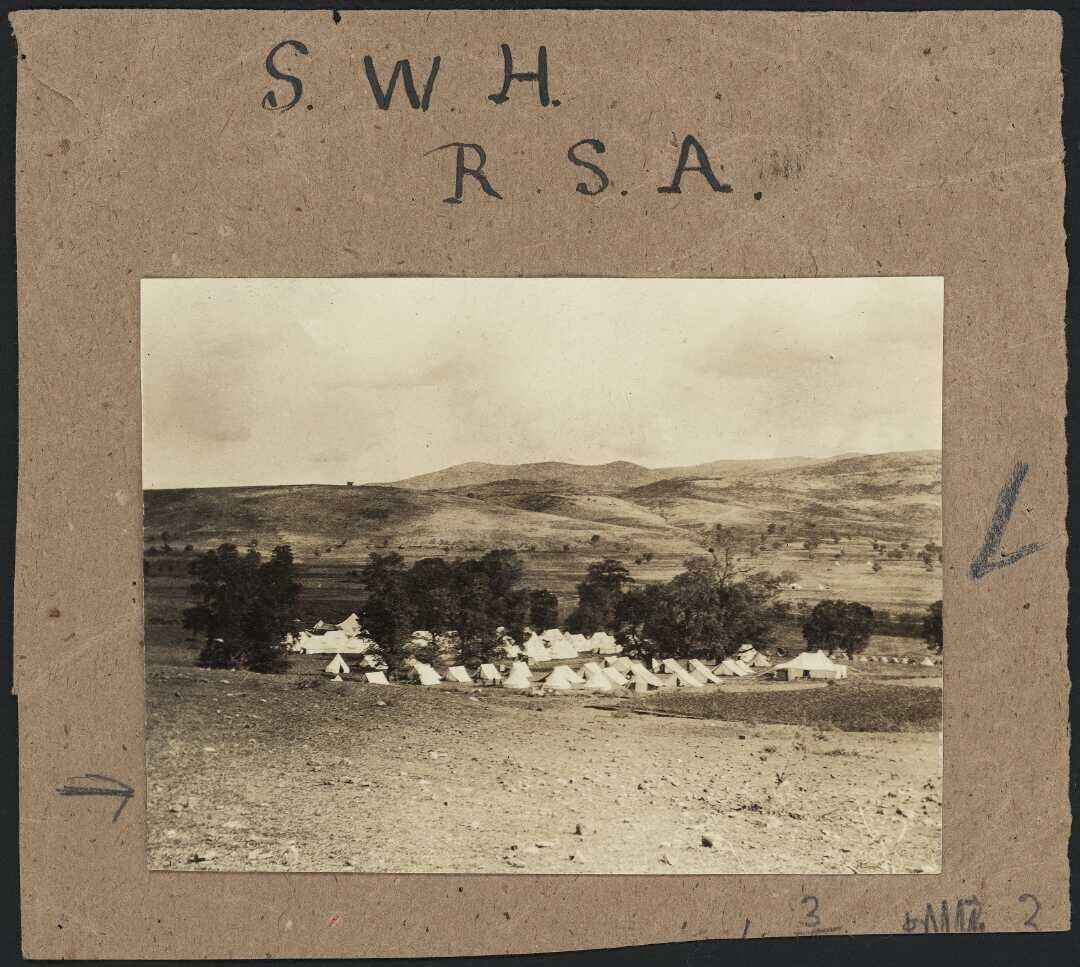

Lilian answered an ad for the SWH in the British Medical Journal and was taken on as a surgeon with a salary of 200 pounds for her years' service and expenses. Josephine accompanied her and signed on as an ambulance driver. They joined the hospital that was originally going to be in Salonika in Greece but was eventually established about 140 kilometres north at Lake Ostrovo, which was nearer the front. This hospital, the 7th Medical Unit of the SWH, was referred to as the Ostrovo or American Unit (as the funding for it came from America) and was for the use of the defeated Third Serbian Army which had retreated and evacuated to Greece, where they established the Macedonian Front.

The Chief Medical Officer of the Ostrovo Unit was another Australian Dr Agnes Bennett and according to her diary they headed off from Salonika on September 5 1916 with 39 vans and a lorry. The camp slowly took shape over the next 2 weeks and the nurses were quick to sew 24 sheets together and make a huge Red Cross to avoid being bombed. The allies (Serbian, British, French, Italian and Russian troops) had started a counterattack against the Bulgarians on 12 September and the Battle of Kaymakchalan was in full swing by the time the move to Ostrovo was complete.

Field hospital of the 7th Medical Unit of the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service, Macedonia, Serbia, during World War I.

When Lilian and Josephine arrived on 18 September, they found the unit situated in a valley, between high bare mountains, where summer temperatures were known to rise above 40 degrees Celsius and the winters were as brutally cold. While most of the camp was under canvas, the main operating theatre was established in a barn. Dr Bennett informed the Serbian Colonel on the day of Lilian’s arrival that they were ready to receive patients and the next day, a convoy of 4 cars set off on the treacherous 22 kilometre journey up the zigzag mountain road to collect patients.

‘We took about 24 cases all terribly bad wounds - abdominal, chest head and compound fractures- it was terrible to see the poor fellows up at the dressing station. 5 died before or just on arrival at hospital.’ (Dr Agnes Bennett’s diary, 20 September 1916)

By the 25th of September, only one week after Lilian and Josephine’s arrival, the hospital had 160 cases and as a surgeon Dr Cooper was putting all her skills to work, with all staff working around the clock.

‘We can only just keep going but we can’t refuse these poor mangled things … I think the compound fractures are the worst we try to save them but there have been 10 amputations in two days and others to come. Those who don’t die seem to get on well and are very happy indeed’. (Dr Agnes Bennett’s diary, 25 September 1916)

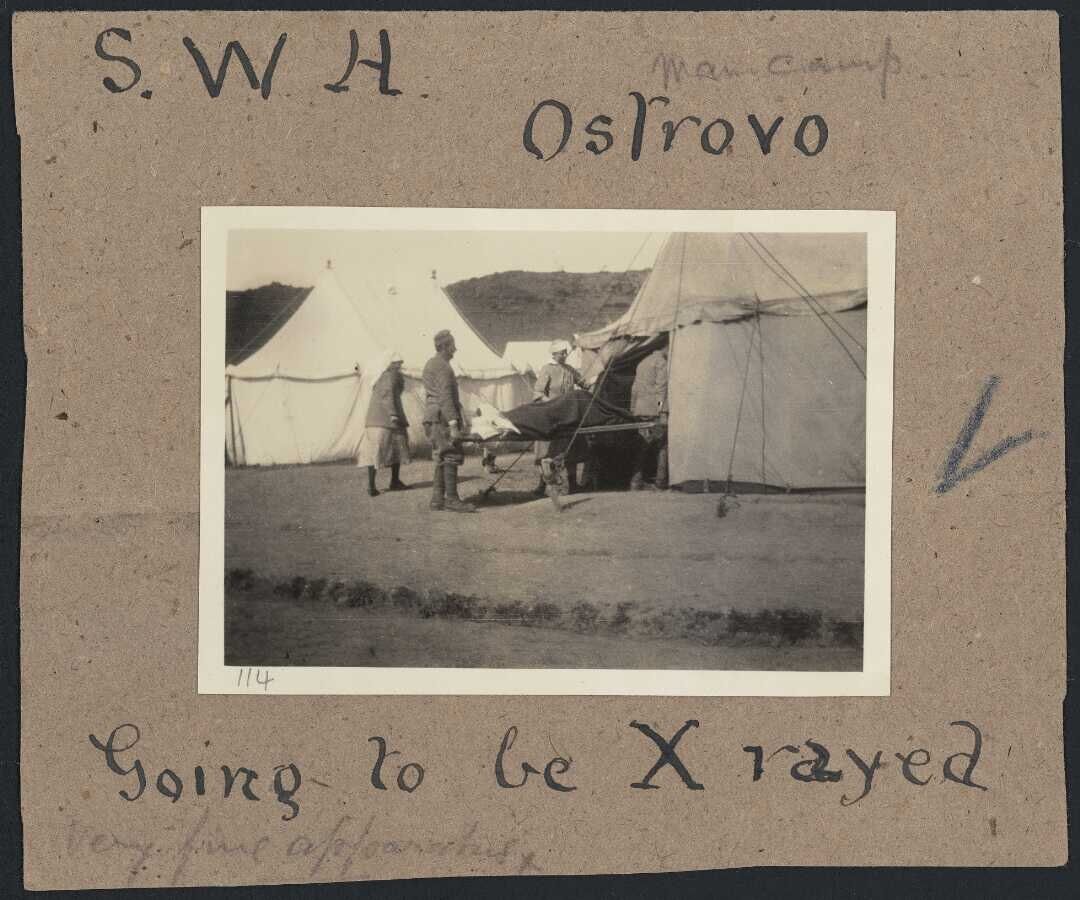

Patient outside the x-ray tent at the main hospital camp of the 7th Medical Unit of the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service, at Ostrovo, Macedonia, Serbia, during World War I.

While at Ostrovo, Lilian oversaw 50 of the 200 beds in the hospital, and implemented strict hygiene protocols that undoubtedly saved the lives of many who might have died in other hospitals. She ensured patients were stripped, washed and put in clean pyjamas on arrival, rather than lying around in their filthy uniforms until operated on. There were many difficulties encountered in this frontline hospital including the extreme weather conditions, which required medical staff to wear woollen gloves while operating in winter. Every member of the unit also came down with malaria. At any one time, up to 14 staff could be unable to work, and one died of cerebral malaria. However, the extreme difficulty of getting transport through to the dressing stations, where the wounded were waiting, was one of their biggest concerns. This, of course, was Josephine’s area as she had been made the transport officer.

‘The chauffeurs are still a trouble but I have given them over entirely to Miss Bedford who has arrived with Dr Cooper. Both are simply splendid and going to be an enormous help to me, being older women’. (Dr Agnes Bennett’s diary, 25 September 1916)

Josephine originally oversaw 5 cars, capable of carrying 4 patients each, a small lorry and a touring car. However, when Mrs Harley, who was later killed by a shell in Monastir in March 1917, left the SWH in December 1916 her transport unit was taken over by the Ostrovo Unit. They then had 18 ambulances, 2 vans and a motor kitchen. Her ability to keep the vehicles serviceable, where spare parts were virtually impossible to come by, earnt Josephine the nickname ‘Miss Spare Parts’ from the female drivers she oversaw.

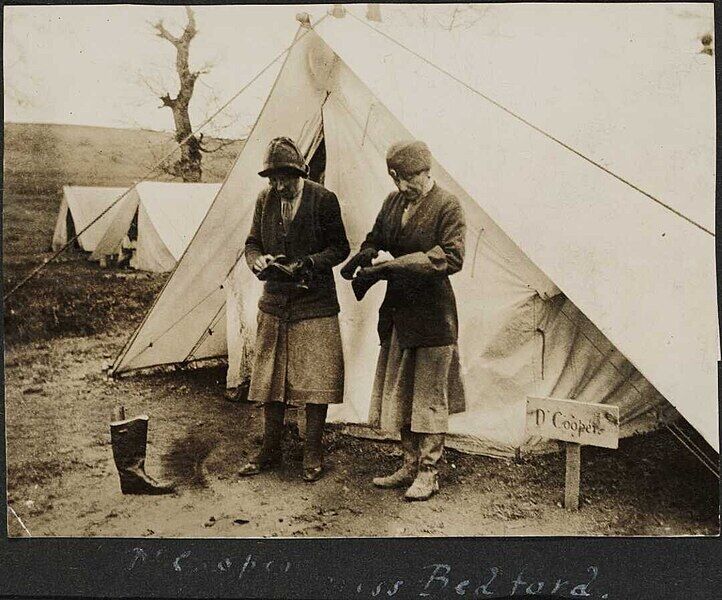

Dr Cooper and Miss Bedford cleaning boots outside a tent, Serbia.

From its opening in September 1916 until the French and Serbian armies captured Kaymakchalan on 19 November 1916 was a very busy time at the hospital. The months of October and November were extremely cold, and it was nothing for the chauffeurs to make 4 daily roundtrips of 28 kilometres. The treacherous roads up to the dressing stations near the front were extremely steep and zigzagged with sharp hair pin bends down the precipitous slopes. Josephine noted that many drivers returned at night with icicles round their necks and their eyebrows frozen. These women not only drove but were often found digging the ambulances out of the mud and snow, pushing them up the hills, washing down their motors and repairing broken parts.

By 23 October 1916 they had admitted 400 patients to the hospital and performed 200 operations, mostly involving the removal of bullets or shrapnel and many amputations. The roads became so bad that by late October they were virtually impassable from mud and the hospital was sometimes quiet as they simply couldn’t get the patients down. As the Serbian line advanced the problem of evacuating the wounded became a bigger issue. Wounded were carried on mules, with no pain relief, to the first dressing stations, then by train to where the ambulances could reach them. Consequently, it was a minimum of 2 to 3 days, sometimes up to 9, before they reached medical care at Ostrovo, which increased the danger of mortality.

‘We are still a long way from our division and it is sad the cases are coming in so long after they are wounded of 9 that came in a few nights ago 4 had to have limbs amputated. Of whom one died and the wounds are so awfully septic it makes terrible work.’ (Dr Agnes Bennett’s diary 2 November 1916)

Members of the Serbian Army bringing in wounded after the battle of Kaymakchalan, Macedonia, Serbia, during World War I.

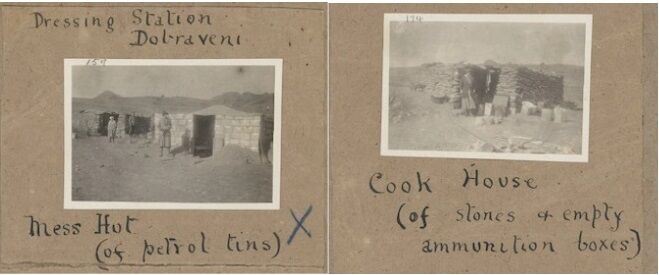

Moving the hospital to follow the Serbian troops was troublesome as they needed to be near the railway from Salonika to ensure provisions could get to them. Ultimately, Dr Bennett proposed a small group from Ostrovo go and start a very simple dressing station nearer the frontline. Lilian was considered the best choice of surgeon to man this outpost and headed off to the Dobraveni Advance Hospital around Christmas 1916. The camp was very simple and located less than 10 kilometres from the enemy lines.

‘They had built a nice little mess house of kerosene tins filled with soil and a tarpaulin roof put up very neatly and were building a place to store things in – the kitchenette was made of stones one on top of another and the roof a hammered out cartridge case they had bought down from the trenches … I went out for a walk over the hills with Dr Cooper. Signs of fighting everywhere even some of the dead not properly buried.' (Dr Agnes Bennett’s diary, 9 January 1917)

Scenes at a dressing station at Dobroveni, Macedonia, Serbia, during World War I.

The wards were in tents and the 40 beds, lent to them by the Serbians, were only about 8 inches off the ground with straw pallets. They did attempt to raise some of them for the more serious patients, using empty shell cases filled with stones, alleviating some of the back strain on the staff. The makeshift operating theatre was in a shed. Wood was scarce and the 5 hour round trip with donkeys to collect it meant it was used sparingly despite the bitter cold.

Early January was fairly quiet at Dobraveni with limited wounded coming in. However, several successful appendicitis operations highlighted the skill of the surgeons in the SWH. By mid-January the workload was increasing rapidly, Lilian was performing operations daily and Josephine’s ambulances were on constant duty. Dr Bennett recorded in her diary that in the 6 weeks from mid-January until early March 1917, 1,840 patients were carried down from the dressing station.

Scenes with ambulances, in Macedonia, Serbia, during World War I.

This forward position was close to the front and prone to heavy bombardment, so the section was given detailed instructions if they were forced to retreat, including the option of walking the 22 kilometres if required. The camp at Dobraveni was ordered to move across to the other side of the Cerna (Crna) River in late March 1917 and, on the day of the move, the winds were howling, and 3 inches of snow was on the ground. Lilian was unable to assist as she was suffering badly with bronchitis. Nonetheless, Dr Bennett, Josephine and the staff, with the assistance of 40 German prisoners, managed to shift the entire camp, except the stores, in eight and a half hours. Lilian was so ill she decided to go to Salonika to convalesce, where she stayed for several weeks.

A month later the camp was moved again.

‘On account of a very heavy bombing attack, we were moved to Skotchivar, about seven kilometres nearer the front, also close to the river. Miss Bedford was at the new camp, and arranged the pitching of the tents, while I remained behind and saw that everything was sent away’. (Dr Lilian Cooper, 1917 as cited in McLaren, 1919).

As summer came to the area, the dust and flies that accompanied the warmer months were appalling.

‘Whatever we did, they got into the food, and it was not an uncommon thing to find an odd fly in your pudding’. (Dr Lilian Cooper, 1917 as cited in McLaren, 1919)

Tremendous dust storms, which could blow the tents down, also swept through in summer. Sometimes the winds were accompanied by flooding rains and the gully beside the kitchen became a rushing torrent taking pots and pans with it.

For Lilian, the opportunity to offer her expertise to such a worthy cause, and be able to perform such vital surgeries, was vindication for all the opposition she had faced during her training and early career. Her long hours of life-saving operations, removing bullets and shrapnel, amputating limbs and repairing wounds, stabilised patients enough for transport down to the hospital at Ostrovo.

‘The bomb wounds, in my experience, were the worst, so many of them developed gas gangrene, and were most difficult to do anything with.' (Dr Lilian Cooper, 1917 as cited in McLaren, 1919)

She saved countless lives, and it has been reported that, during her 8 months at the dressing station, only 16 of the 144 patients she operated on died. That she did such marvellous work under the most basic conditions, and in such an inhospitable and dangerous environment, is a testament to her skill and endurance.

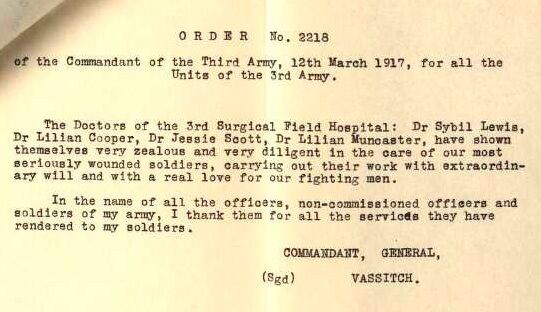

Order sent to Units of the Third Serbian Army, 12 March 1917.

Both Lilian and Josephine admired the Serbian people they helped care for. They talked warmly of their bravery under the extreme circumstances of their position in the war. Not just the wounded soldiers from the battles of Gornicevo, Kajmakcalan and Monastir (Bitola), but the refugees that had come with them during the retreat. Air raids dropping both incendiary bombs and poisonous gas shells were frequent in the areas near the frontline killing and injuring both civilians and military personnel. During a talk Lilian and Josephine gave in 1918 to raise funds for the Red Cross, Lilian noted:

‘It was jolly unpleasant. When a Boche plane came and dropped bombs all around the hospital, some within 50 yards of the patients’ tents. Honestly, I was never so frightened in my life.' (Dr Lilian Cooper lecture, Wednesday 10 July 1918, as reported in the Daily Mail Thursday 11 July 1918)

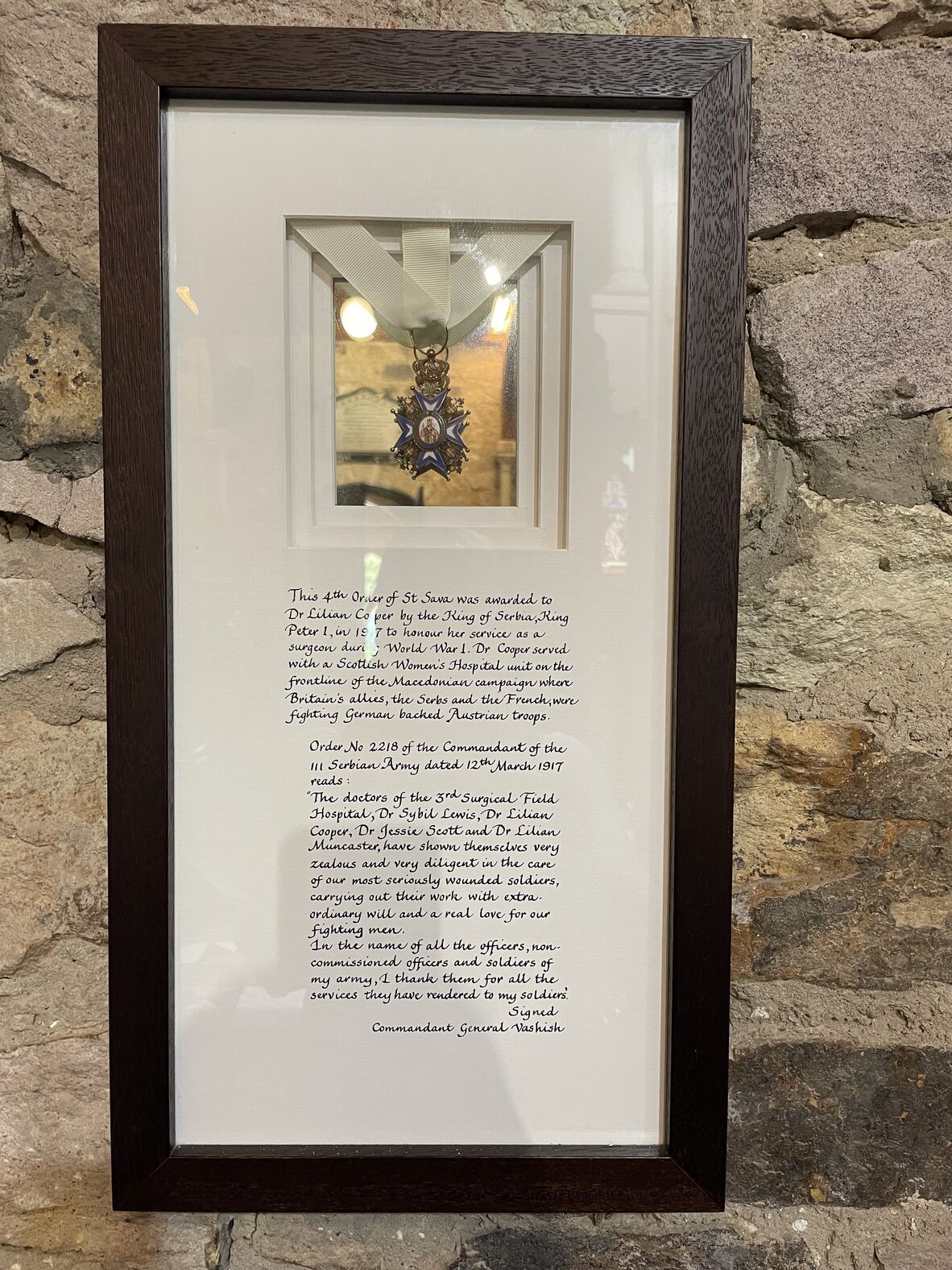

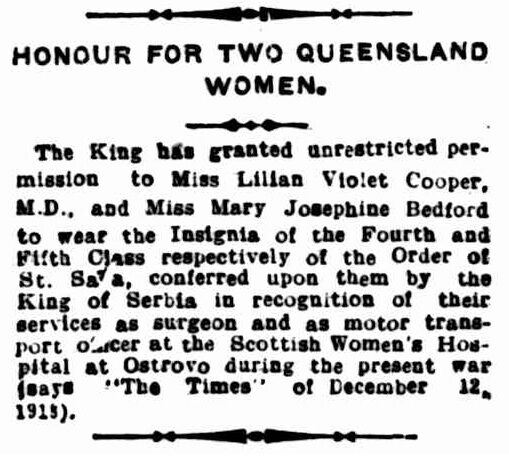

Their tireless work was greatly appreciated by the Serbians and, in 1917, King Peter I of Serbia awarded Lilian the 4th Order of Saint Sava and Josephine the 5th Order of Saint Sava.

Dr Lilian Cooper’s Order of Saint Sava.

An article in The Brisbane Courier about the two receiving their honours.

In September 1917, Lilian was once again seriously ill with bronchitis, so a year after their arrival she and Josephine left the SWH and returned to London. They stayed in the United Kingdom for several months before returning home to Brisbane in April 1918. During interviews and talks about their experiences both ladies were very modest when recounting their astonishing accomplishments. Lilian tirelessly performed operations day after day in some of the harshest conditions, and Josephine drove and maintained ambulances which traversed the most rugged terrain. These brave women faced death and provided faithful service through their determination and persistence in getting to the front. Their involvement in the war not only provided medical assistance to the Serbian Army but helped promote the cause of women’s rights.

Further reading:

State Library blog - Dr Lilian Cooper and Ms Josephine Bedford | State Library of Queensland

Lilian Cooper: Dangerous Women Podcast Series State Library of Queensland, https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/tqqf2h/alma99183850921002061

Dr Agnes Bennett, Extended diary of service, 1916-1917, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

References:

From Lilian Violet Cooper to Australia’s other pioneering female military surgeons of World War I - Australian Women at War,2021, Australian Women at War, viewed 7 February 2025, https://australianwomenatwar.com.au/from-lilian-violet-cooper-to-australias-other-pioneering-female-military-surgeons-of-world-war-i/

Two Women: Dr Lilian Cooper and Josephine Bedford, 2019, Destiny Rogers, viewed 7 February 2025, https://qnews.com.au/the-story-of-two-remarkable-queensland-women-who-deserve-their-place-in-history/

McLaren Shaw, E (ed) 1919, A History of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, Hodder & Stoughton, London.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.