Reviewed by Elizabeth Fielding, Legal Deposit Coordinator, State Library of Queensland

A White Australia authored by a “special commissioner” for the Melbourne Herald in September 1901, is essentially about the economic, social and political repercussions of using labour from the South Sea Islands to support the sugar industry in Australia's north. As the rather convoluted title suggests, there are essentially three key players in this fascinating (and at times unsettling) publication: sugar, the indentured South Sea Island labourer and the White Australia policy.

Described as an “investigation” into the sugar industry and the “Kanaka labor question”, the booklet consists of a series of minutely researched articles published between May and September 1901, all of which address “a highly important and perplexing question of public policy”.

Indeed so important was the question as to whether the viability of the sugar industry - and the prosperity of Queensland - were dependent on Polynesian labour, the issue framed debate as to whether Queensland should exclude itself from the Commonwealth in the interests of preserving the trade in indentured labour.

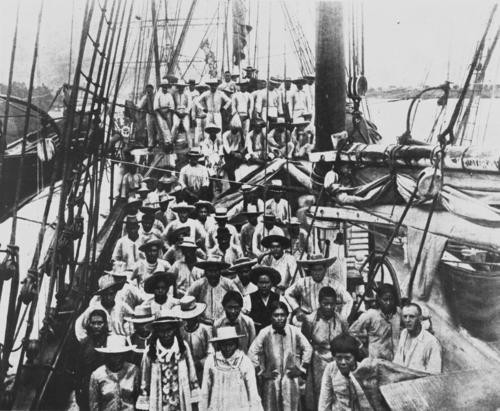

The author traces the history of the trade in South Sea Islanders from the early 1860s and makes chilling reference to the atrocities practised by “rapacious and cold blooded scoundrels who engaged in recruiting islanders were ruthlessly torn from their homes and kindred”, having been “enticed by all sorts of specious means to place themselves within the grip ”.

These articles detail the succession of imperial and colonial acts which sought to modify the excesses and cruelty of the early trade and which resulted in a system licensed by the Government Immigration Agent. The regulated system was based on voluntary enlistment (usually from Melanesia or the New Hebrides group), a minimum wage (fixed at £6 a year), a three year term of employment, rations and clothing, basic accommodation, medical care and provision for a return passage. Responding to the concerns of a colony which had essentially declared its aspirations for a “White Queensland”, the granting of a licence was limited to “field work” associated with tropical or subtropical agriculture (sugar, coffee, cotton, tea, coffee, rice and spices).

An attempt to phase out indentured labour under the Prohibition Act of 1885, in accord with the majority view expressed in the 1883 state elections, was unconditionally repealed seven years later in 1892 following a Royal Commission of enquiry which concluded that:

"sugar cannot be grown profitably, at least for export, without the employment for hand work in the field of a class of labor cheaper and more suitable for the work than white labor".

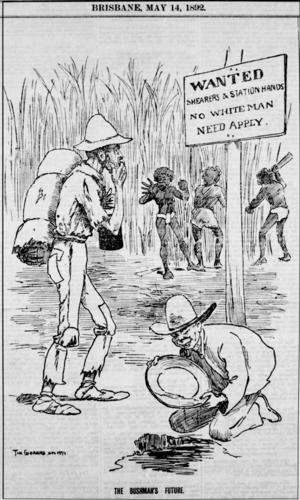

Several pages are devoted to the argument which led to this outcome, the essential debate being about the economics of sugar growing and the capacity or willingness of white men to undertake heavy physical labour in the humid north. Those advocating a White Australia policy tended to support Prime Minister Edmund Barton's belief that “the industry can ultimately be worked by white labor, and that in the meantime it is entitled to consideration”.

The opposing view was that it was “in the best material interest of the white population that in order to provide for the work of the sugar fıelds, the importation of natives of the South Islands should be continued”. This argument was augmented with the view that:

"the sudden curtailment of the employment of the Kanaka, restricted as it is to fıeld work, will force the sugar farmers … to fall back on the Indian Coolie who cannot be restricted to field work, and who may in time prove a most undesirable competitor to our artisans and labourers".

The testimony gathered in consideration of the critical question about the sugar industry and the impact of indentured labour is far reaching and instructive in terms of what it reveals about the social circumstances endured by South Sea Islanders. The undeniable evidence of an “awful sacrifice of human life” is underscored by a disturbingly high death rate (40 per 1,000 South Sea Islanders as compared with 12 per 1,000 in the white population and in the islands) and 180 per 1,000 amongst Islanders who had spent less than 6 months in the colony.

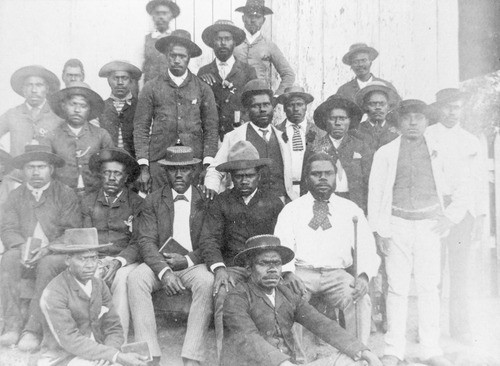

The Melbourne Herald correspondent provides some telling detail about how the 9,000 or more South Sea Islanders lived in Queensland’s north. Conditions in the field, where they toiled barefoot, were steamy, ferociously hot and conducive to lung disease. They lived in huts built of reeds, largely without the companionship of women ( the ratio of South Sea Islander labourers being estimated at between 5 and 10 women to every 100 men) and they were the victims of a dangerous and illegal trade in “the very worst” brand of sly grog. Their extreme social exclusion is attested to by the existence of at least 60 “Japanese prostitutes” who, along with an indeterminate number of “low white women”, were permitted to operate out of brothels in Cairns and Bundaberg “to safeguard our own women kind”, the fear being that “having regard to the number of Kanakas and other coloured aliens, …our own wives and daughters would not be safe”.

Such observations about the social conditions experienced by South Sea Islanders are offset against an exploration of the sugar industry in its every aspect. The articles investigate the large co-operative sugar mills established in the interim between the prohibition of indentured South Sea Islander labour in 1885 and its repeal in 1892 - and they cover in some detail the correspondent’s field trips to districts around Cairns, Mossman, the Johnstone and Herbert River districts and Bundaberg. They describe the essential business of sugar production – land clearing, holing, planting, weeding, trashing, cutting, ratooning crops and transporting the cane. They examine the economics of employing “Kanaka” labour and look in detail at the system of tenant farming governed by the Cane Agreement which encouraged white farmers to clear, plant and cultivate portions of land for sugar production.

The prevailing and persistent opinion in the north, voiced largely through interviews with plantation owners and white farmers is that “without the Kanaka the industry would perish”. Only occasionally is a dissenting voice raised – and, from the distance of 2013, it seems quite remarkable that even the realisation that “we are not, as professed Christians, entitled to discriminate against men of color” is underwritten by a strident note of paternalism. While recognising that discrimination is “an unworthy and unrighteous thing to do” it was also believed that the white colonial establishment “civilize and elevate” the South Sea Islander.

The conclusions drawn by our correspondent (whose self declared mission is to “collate …the essential facts…fairly, impartially and, at least, without conscious bias”) are, to say the least, disconcerting. On the one hand he expresses the opinion that white men can do all the essential work of sugar growing” and that “it will pay to grow sugar with white labor”. He recognises moreover, that “black traffic is only thinly disguised slavery” and that, given the South Sea Islander death toll, “the sugar industry of Queensland has been baptised in the blood of the black man”. In this vein he quotes the Polynesian missionary, the Reverend William Gray who describes the “Kanaka labor traffic …a cruel, unjust, un-Christ-like demoralising traffic in human flesh”.

On the other hand he also raises concerns about “miscegenations” and the hypothetical "menace to the white man’s wife and daughters”, making reference to Islanders, on more than one occasion, as “mere savages”. It is, however, in his final rhetorical flourish that the author's "moral" perspective is distilled. His appreciation of the injustice suffered by indentured South Sea Islanders is ultimately qualified by an overriding concern about the perceived threat they pose to the “civilized” interests of “a Christian state under the British flag”.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.