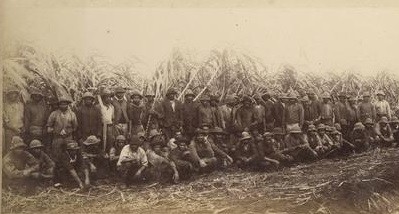

Digitised @ SLQ: Employment of Polynesian labour in Queensland, 1894

By JOL Admin | 28 June 2013

A few facts in connection with the employment of Polynesian labour in Queensland, 1894

The purpose of this 1894 publication is to undermine and contradict the efforts of the Rev Dr Paton who at this time is actively protesting against Polynesian labour engagements on Queensland plantations. Two very different perspectives on Polynesian labour engagements are revealed. At one end of the spectrum Rev Dr Paton believes that “the evils that are heaped upon the defenceless Islanders just as they are emerging from the long black midnight of heathenism and cannibalism and of a deadly system that must lead to abuse, bloodshed and God-dishonouring cruelty, little short of that accursed thing called slavery.”

On the other extreme the author, Maurice Hume Black, believes that not only has the Colony “been enabled to maintain an important industry, the labourers themselves have been benefited by being brought under Christianising influences, and by being inculcated with habits of thrift and industry.” The opinion put forward by this publication is well summarised by the Rev Mr Eustace who refers to Rev Dr Paton as “a sort of mad enthusiast with a hobby and his charges where legitimate are grossly exaggerated and are otherwise entirely unfounded.”

At the time of this publication, 1894, Rev Dr Paton has been protesting to the Colonial Office and has also been trying to enlist the sympathies of the people of Great Britain through missionary meetings. He describes Polynesian labour engagements in Queensland as “so terrible a nature that if true would demand the intervention of the Imperial Government”. Rev Dr Paton claims that the Kanaka Labour business “has been demoralising and ruinous to all connected with it” and that “the atrocious crimes and murders connected with the traffıc are a disgrace to humanity and to all Queensland”. He claims that “their long hours of labour and hard work and changed circumstances of food, clothing and houses, have caused unexampled mortality amongst the Kanakas” and “that when they died they were buried like dogs”. Rev Dr Paton asserts that “dreadful immorality was encouraged amongst them” that “the cruel oppression and bloodshed cry to Heaven for vengeance” and that “it is the worst kind of slavery”.

The author Maurice Hume Black, Special Agent to the Queensland Government, sets out to contradict Rev Dr Paton’s description of conditions and asserts that they are based on out-dated knowledge of conditions and are no longer accurate. He claims that Rev Dr Paton’s ” has not paid even a flying trip to the sugar plantations of Queensland during the past decade.” To make his case Maurice Hume Black quotes a series of officials who contradict Rev Dr Paton’s assertions. For example, Rear Admiral Lord Charles Scott, C.B., Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Squadron of the Royal Navy claims that “no fault was to be found with the recruiting system since 1885, and that he cannot, after careful consideration, condemn it” while Sir Samuel Griffıth, Chief Justice and formerly Premier of Queensland, states that “no serious complaints of kidnapping have been made since 1885, and the abuses of former days have long since come to an end.”

The great benefits of the sugar industry to Queensland are also brought into the argument to support the benefits of Polynesian labour engagements. It is stated that the sugar industry “has given employment to nearly 30,000 European managers, overseers, mill hands, ploughmen, artisans, &c. It has cleared the ground of jungle and brought under cultivation 50,000 acres of the Delta and coast lands of the colony ; has given an impetus to maize growing, to horse-breeding, to cattle raising on the seaside of the coast range ; has started foundries and engineering establishments in all sugar centres; has built up a fleet of coastal steamers second to none in speed and accommodation”. Significant emphasis is also placed on the importance of the religious instruction received by labourers. Maurice Hume Black gives extensive examples of efforts to improve the moral welfare of the islanders. These include the views of Mrs Donaldson, the wife of a planter at Mackay, who wrote to the “Australian Christian World” “My labour of love has been a very encouraging and pleasant one. I believe that the “boys” are easier to win and that mission work is consequently more successful here than in their own islands, and for this reason, that they are away from their heathenish prejudices and superstitions. I had a letter from a missionary (in the Solomon Islands) quite lately, and he spoke of the good behaviour of some boys returned from Queensland.”

Perhaps one of the most disturbing quotes in this publication are those designed to show that the mortality rates suggested by Rev Dr Paton are exaggerated. Maurice Hume Black quotes from a speech delivered in the Queensland Legislative Assembly by D. H. Dalrymple, Esq., M.L.A., on 7th April, 1892.

“It is ridiculous to compare the death rate of Polynesians in the Colony with the death rate among Europeans unless you can show that the death rate of Polynesians under normal conditions when they are in their own islands is the same as the death rate amongst Europeans in the Colony.

In Tonga in 1847 there were some 40,000 people, now there are 10,000.

In the Society Islands in Captain Cook’s time the population was put down at 68,000, now there are 9,000. There are no planters there but there are missionaries.

In the Marquesas islands in 1870 there were 50,000 natives, in 1879 there were 4,000.

At Anietam in the New Hebrides there were 12,000 people twenty-fıve years ago. There are missionaries there and the population now is 2,000.

Take the Maoris. They are a declining race. The Tasmanian is practically extinct. The Australian Aboriginal is rapidly becoming so. In the islands where the conditions are normal and favourable where they have missionaries, where they have no violent wars and no recruiting these people are declining.”

This book review is part of an ongoing series by State Library staff who have volunteered to review heritage collection materials about labourers who were brought to Queensland from the South Sea islands beginning in 1863.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.