Guest blogger: Lisa Jackson - 2017 Q Anzac 100 Fellow

The Dunwich Inebriate Institution – located within the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum on North Stradbroke Island - was the only place in Queensland responsible for supporting alcohol-affected soldiers in the period after the First World War. However, over 220 returned soldiers who were committed to the Inebriate Institution – either by choice or by being sentenced by a magistrate – didn’t receive the kind of treatment or rehabilitation the existence of such a place promised.

Until 1925, returned soldiers who had turned to drink as a result of their war trauma were admitted to the Asylum as inebriates, although they were mainly suffering shellshock. After serving a three month sentence – or a maybe a couple of these short sentences – most patched up their lives and moved on.

Others were serious alcoholics even before they enlisted, or become alcoholics as a direct result of their war service. One of these was returned soldier Leland Virgil Edmund Noel, one of the most colourful characters of Brisbane in the postwar period.

Sketch of Leland Virgil Edmund Noel. Published in the Truth (Brisbane), October 19, 1913, p.6

Noel was a committed alcoholic with a very long list of convictions when he enlisted in 1917. He suffered delusions and mental instability, and was discharged at Cape Town with pre-existing acute alcoholism. After returning to Brisbane, he was admitted to the Inebriate Institution three times before 1921.

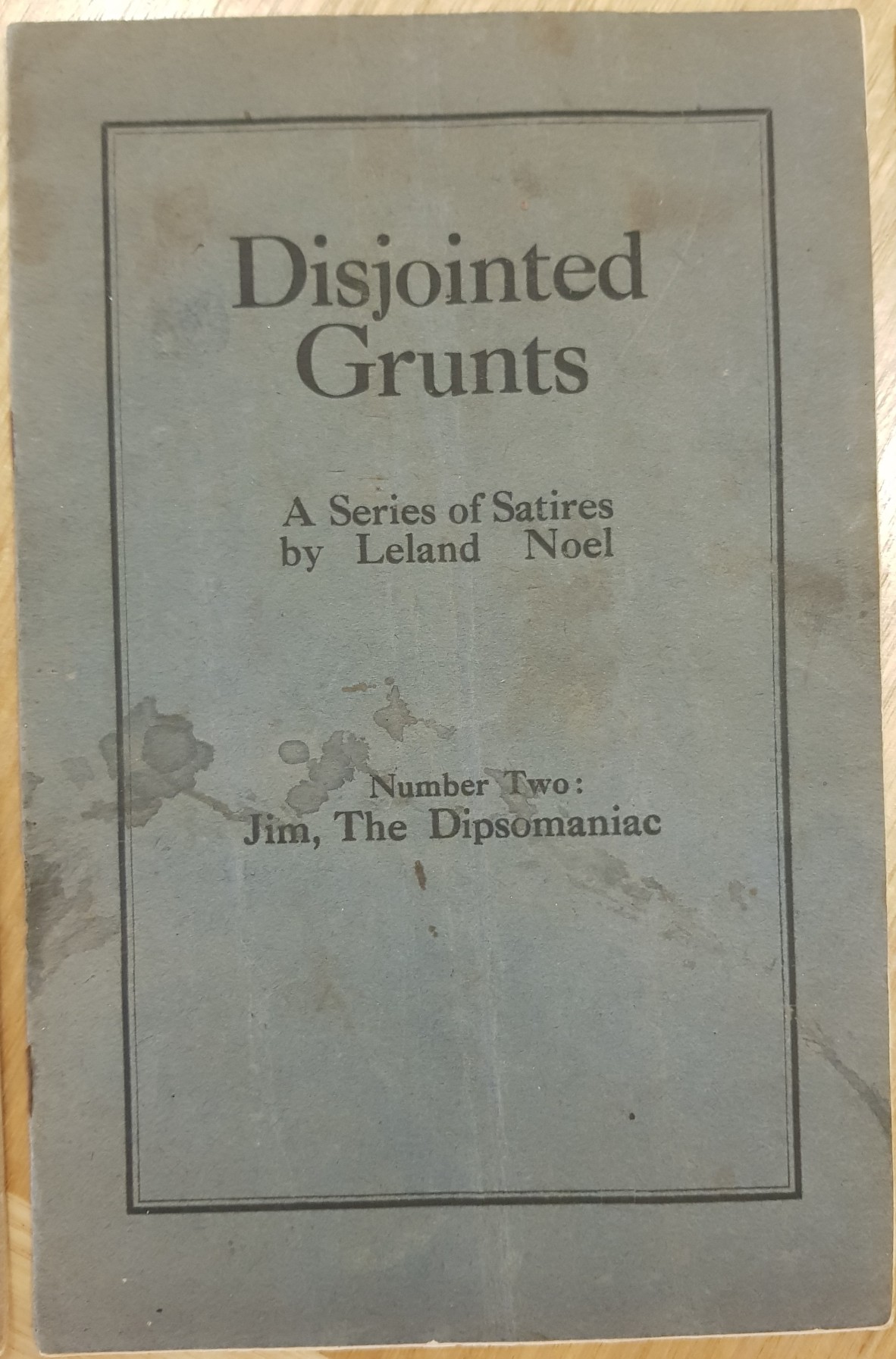

Leland Noel worked as a journalist and published several small volumes of satirical prose. Two of these can be found in the SLQ collection. This excerpt in particular gives a modern reader an insight in to the sufferings of those addicted to alcohol.

“To place a man in gaol for drunkenness, with the idea of deterring, curing or improving him, is contrary to the dictates of reason... In the gaol history of the world, there has only been one man, who after having served a sentence for drunkenness, did not get drunk, upon discharge, at the first hotel: and that one lonely single fellow did not get drunk at the first hotel because he had delusional notions that the grog was better at the second, and he dropped dead in his excitement to get there.”1

Leland Noel was right to be cynical about gaol being the recommended treatment for alcoholics in the early twentieth century, given his first-hand experience.

The Inebriate Institution was intended to be a dry community. Its isolation from the temptation of the pubs of towns and the city was a key reason inebriates were sent to the Island. The Medical Superintendent did, however, allow rum or beer to be added to the rations of the ordinary Asylum inmates on special occasions, and it was customary for men who worked within the Asylum to be issued a rum allowance in lieu of payment. Some inmates were prescribed a daily dose as medicine. These prescriptions were inevitably saved up and traded to those willing to pay, and the inebriate inmates were ready buyers.

There is evidence that the inebriates were subject to a curative treatment of atropine and strychnine with liquor when the Institution was at Peel Island prior to 1916. 2 But Dr James Booth-Clarkson – a man with a long military career and Medical Superintendent of the Asylum from May 1918 - considered that the best treatment for alcoholism was sedation for several days, then a regime of abstinence and hard work. He was convinced that alcoholism was a weakness in character, rather than a symptom of trauma.

When the State Government responded to pressure from the public and the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia (RSSILA), and decreed that returned soldiers should receive better rations, be housed in their own ward and should not be required to work at the Asylum, Dr Booth-Clarkson resented what he saw as special treatment for the soldiers. He wrote in his 1919 Annual Report:

“This is a very serious defect especially so far as the Soldiers are concerned as it means that a number of young or youngish men are getting into the habit of not working and find the position so comfortable that there are frequent requests for extension of time, and in many cases there are readmissions which is not to be wondered at when the surroundings are so comfortable and pleasant.”

For many years, Dr Booth-Clarkson advocated for all the inebriates to be moved to Peel Island or to St Helena, which he considered more suitable for disciplinary and reform purposes.3 He had lived in the United States, and was influenced by the prohibition and temperance movements there. He saw alcohol as tempting “weak brothers”, and lamented the role of barmaids in creating a reason for men to hang around bars.

Booth-Clarkson himself noted that “Unfortunately there seems to be no Society in Brisbane similar to the Social Services of the United States, which looks after such men on discharge and sees them safely to any occupation they have obtained.” The Repatriation Commission refused to consider alcoholism as a war-related condition, and cancelled pensions and benefits for any returned servicemen they suspected as using their funds to buy alcohol. Even charitable organisation such as the Red Cross and the YMCA did not have the resources, capacity or the will to house drunken men in their homes for returned soldiers.

At no time did inebriates receive what would be considered appropriate medical treatment for their alcoholism. Around half of the soldiers who were discharged after their sentence returned to the Institution at least one more time. A succession of Medical Superintendents seemed to be at a loss as to how to deal with their needs.

If inebriate inmates broke their prohibition orders, the Medical Superintendent would resort to banishment. This is what happened to Leland Noel, three other returned soldiers and an Aboriginal worker in the Asylum named Tom Tate in 1921. It appears Tom Tate took a boat to Dunwich on Christmas Eve, with a shopping list from a number of Inebriate Institution inmates. Four soldiers subsequently had a party with the assistance a bottle of whisky, three of rum and a dozen bottles of beer. This resulted in an all-night drunken brawl, where a soldier’s face was wounded by a heavy piece of iron piping, a wardsman suffered a broken nose and at least one soldier being found near the visitor’s quarters, frightening some young females who were spending Christmas with their relatives. All four returned soldiers – as well as Tom Tate – were expelled from the Asylum.

Being denied appropriate treatment for his alcoholism didn’t work out well for Leland Noel. In 1930, he was admitted yet again to Dunwich, this time with “optic atrophy”- blindness caused by drinking methylated spirits. When he passed away in the Asylum a few months later, the local papers noted:

NOEL DEAD. The death occurred at Dunwich on Monday last of Leland Noel, perhaps one of the best known figures in Brisbane for years: A son of the late Judge Noel, Leland was in his youth, one of the finest athletes of his time, and was a remarkably good player of Rugby Union football. He had considerable literary talent, and at times produced some pleasing poetry. He was about 52 years of age.4

Some of his “pleasing poetry” is preserved in the State Library collection. It records his lifelong battles with authority, and with drinking. One example:

“O dipsomaniac! Can you ever forget those Sundays you spent in the dank, darksome, lousy, foetid lockups, when you saw your own hopelessness written in your brothers’ tragic eyes? Can you ever forget that fellow who died in the corner, the hideous convulsions of his terror, and his last delirious utterances which seemed goitred in his throat? Can you ever forget that awful night when you leapt with a scream from that semi-coma or half-sleep of “the recovery” when you felt and smelt the presence of death; when lockup lice, like lazy lizards, wormed through the alcoholic ooze of your suffering self-loathed self, and in the phantasmagoric delirium of your preternaturally terrored eyes, canine-fanged fiends fandangoed lasciviously with betailed and naked harlots, hissing madrigals of hell?”5

For Leland Noel and hundreds of other returned soldiers, the reliance of the State Government and the Repatriation Commission on prohibition and the isolation of the Inebriate Institution as an effective treatment, was clearly a “delusional notion”.

Lisa Jackson - 2017 Q Anzac 100 Fellow

References

Noel, L. (1920). Disjointed Grunts : A Series of Satires : Number One: Mary Brokenheart / by Leland Noel. SLQ Collection.

Report from GW Jackson, chief attendant, July 1916. Queensland State Archives Item ID279743, Batch file

The Annual Report of the Inebriate Institution, Dunwich, for the Year Ending 31st December 1919. Queensland State Archives Item ID18242, Batch file

1930 'LELAND NOEL DEAD.', Daily Standard (Brisbane, Qld. : 1912 - 1936), 23 July, p. 6. , viewed 24 May 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article178916279

Noel, L. (1920). Disjointed Grunts : A Series of Satires : Number One: Mary Brokenheart / by Leland Noel. SLQ Collection.

https://vimeo.com/269106767

Further reading from Lisa Jackson

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.