Chinese Business History in Queensland - Gold rush: 1851-1881

By JOL Admin | 14 May 2020

Guest blogger – Rutian Mi, 2019 Queensland Business Leaders Hall of Fame fellow.

In 1851, the discovery of gold in NSW and VIC started a gold rush. People gave up their jobs and families to get to the gold field, including teachers and policemen. Even the sea crews abended their ships and rushed to gold field leaving vessels stranded in the port. A Chinese man sent a letter to his hometown in Guangdong and 3,000 Chinese came to Melbourne for “Xin Jin Shan -New Gold Mountain” (Chinese call California “Jiu Jin Shan-Old Gold Mountain”).

During 1851-1856, there were about 50,000 Chinese that came to Australia for gold. The conflict on the gold fields caused many anti-Chinese riots during this period as well.

Our two subjects of the case studies were born during this period in the same year: 1853. Tom See Poy 1 May 1853 and Kwong Sue Duk 4 September, 1853.

In 1859, Queensland separated from New South Wales.

In 1861, NSW passed the ‘Chinese Immigration Restriction and Regulation Act’.

Queensland’s gold rush was later than New South Wales and Victoria, but the Chinese population in QLD was growing quickly since the first Chinese arrived in Brisbane in 1848.

In 1860, there were 286 Chinese in Queensland. One of the famous Chinese businessman Andrew Leon settled in Cooktown in 1866. Andrew didn’t come to Australia as a gold digger, he worked in tropical agriculture in the West Indies, including two years in Cuba. Andrew moved to Cairns in 1876 and set up the first Chinese store in Cairns. Andrew is the pioneer of Chinese business in QLD. In 1878, Andrew set up ‘Hap Wah plantation Company’, the First Sugar growing venture in Cairns.

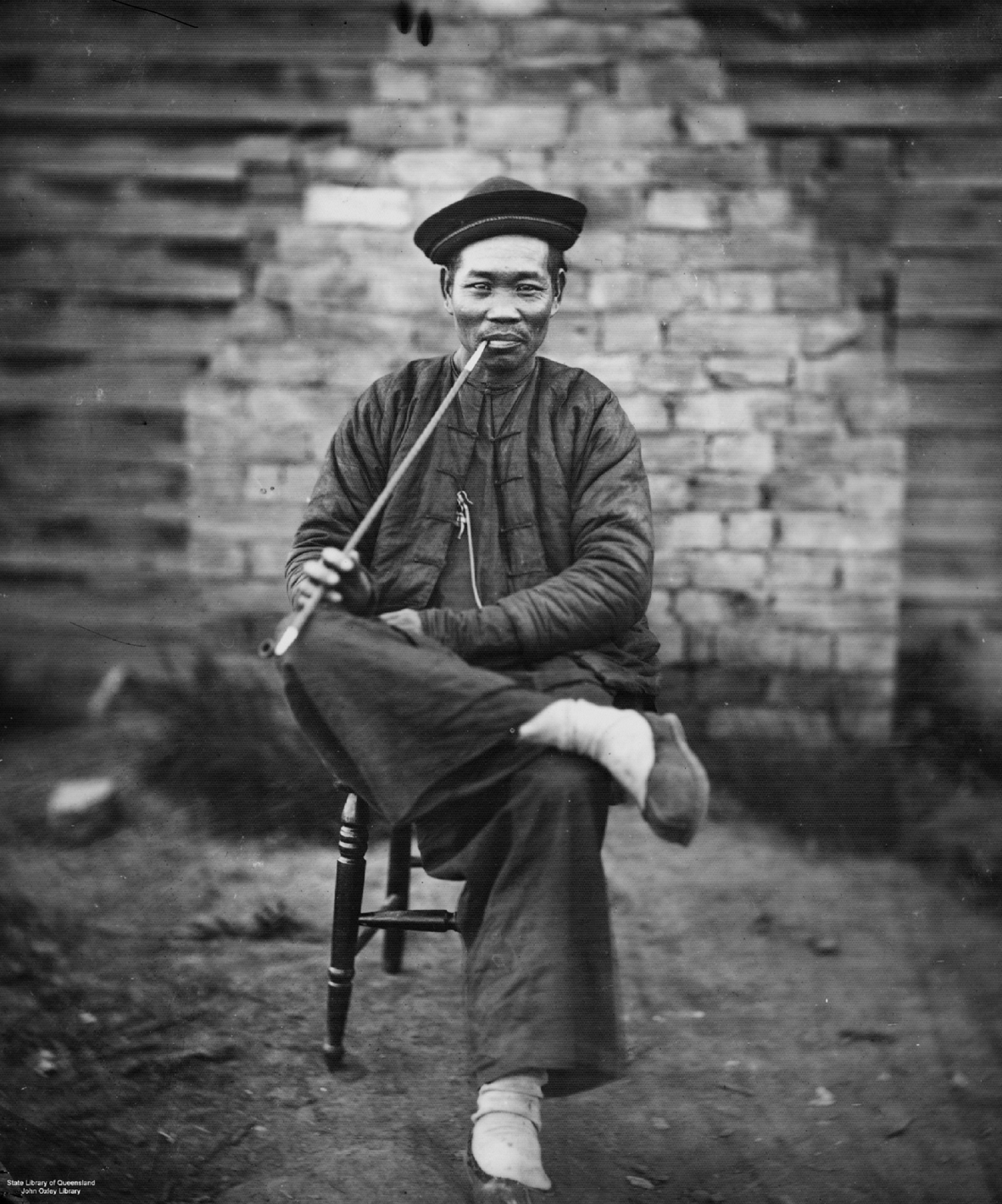

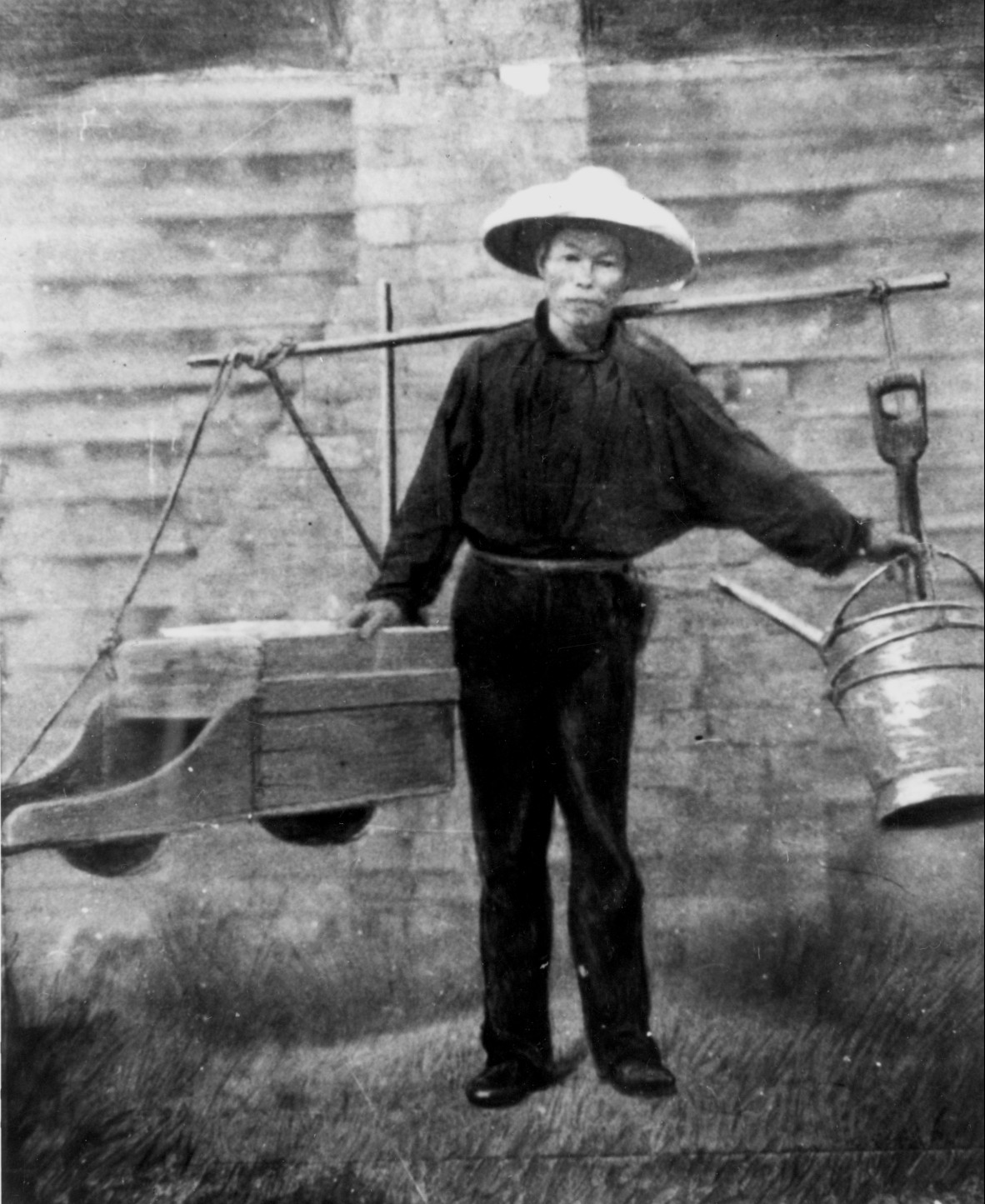

In 1867, gold was found in Gympie then Palmer gold field started in 1873. There are two photos in John Oxley library showing two Chinese gold diggers starting for work and relaxing after work in 1860s.

Chinese miner in traditional garb relaxing with a long stemmed pipe

Chinese gold digger starting for work, ca. 1860s

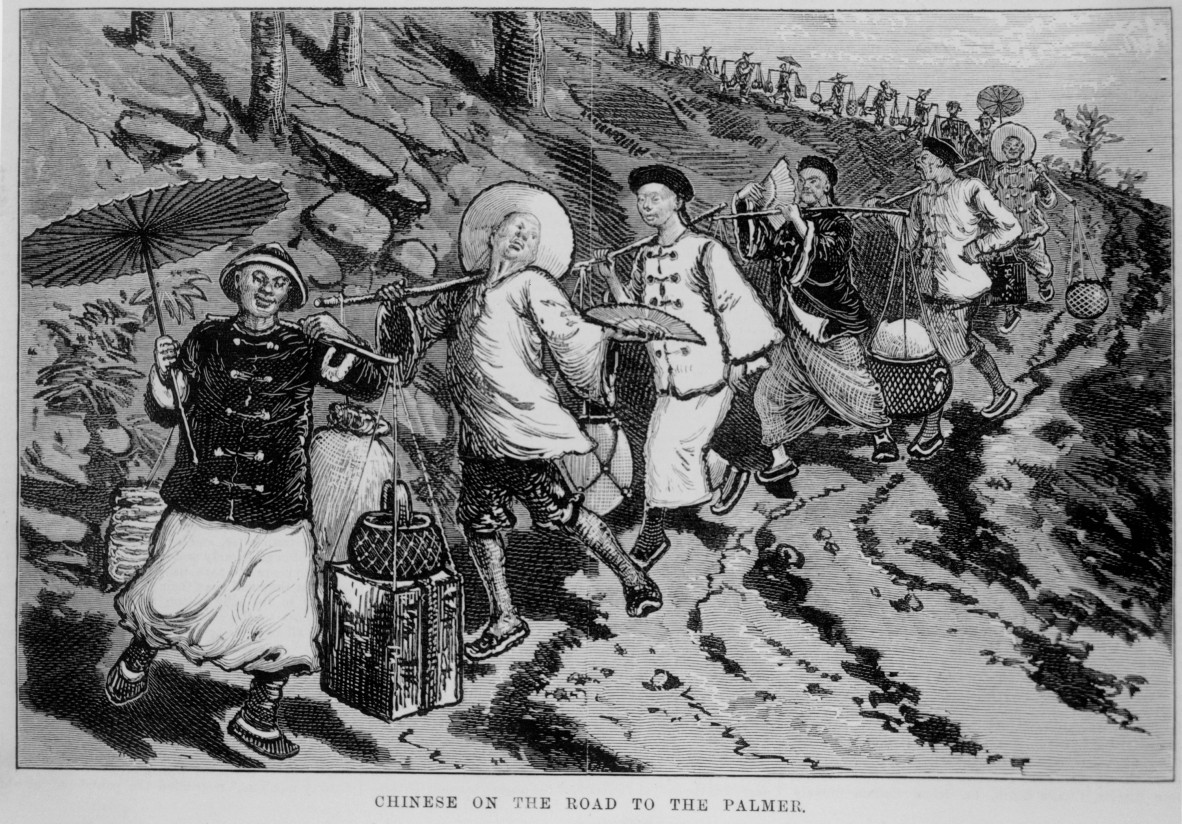

There is also a drawing of ‘Chinese on the road to the Palmer’ published in 1875 collected in John Oxley Library. The drawing shows a group of Chinese people happily marching to Palmer Gold Field. The first person seems to be a leader wearing traditional Chinese dress, officer hat and holding an umbrella. They were all carrying goods using Chinese shoulder pole.

Drawing of Chinese people on the road to the Palmer Goldfield, Queensland, 1875

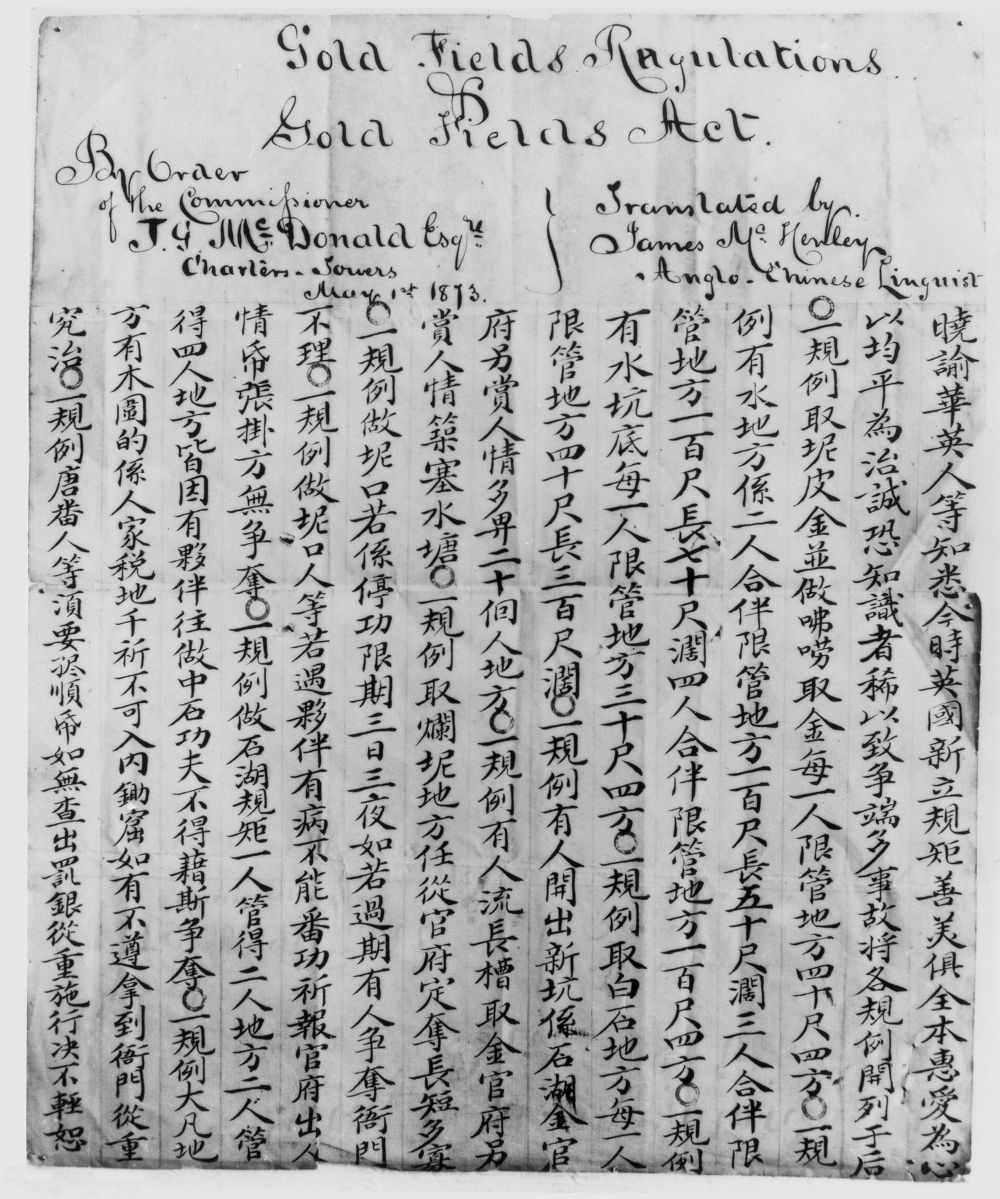

It seems Chinese gold digger had a good time in the beginning. With the increasing competition, the Chinese gold diggers were requested to follow “The Gold Fields Regulations and Gold Fields Act”. There is a copy of Chinese translation in John Oxley collection. The translation was 'By order of the Commissioner J. G. McDonald Esqre., Charters Towers, May 1 1873’ and ‘Translated by James McHenley, Anglo-Chinese Linguist'. Hand-written in Chinese characters.

Chinese translation of the Gold Fields Regulations and Gold Fields Act, 1873

In 1877, See Poy came to Palmer River with his father, brother and many other Chinese gold diggers. See Poy was born in a poor family and their journey to Palmer was not as joyful as showing in the 1875 picture.

According to See Poy’s ‘My Life and Work’ published in 1925 “Not only was gold difficult to find the climate is not suitable and was the cause of frequent attacks of illness’. When he arrived in Cooktown, he saw ‘the staved looks of our fellow countrymen who were either penniless or ill’. He described the hard three-month journey from Cooktown to Palmer gold mine. In his book, he also mentioned a man called ‘Mr Chan Poo’ (陳盤) who treated his father and brother’s eruptive fever without charge.

After 5 years, See Poy realised ‘search for gold was like trying to catch the moon at the bottom of the sea’. So he started working in a restaurant ‘at the wage of two pounds a month’. See Poy must have been working very hard and perhaps got a bonus, because at the end of the year, he saved ‘twenty-five pounds, sixteen shillings and six pence, after deducting expenses’.

A couple of times, See Poy thought about returning to China. Once his uncle mortgaged their family house for $160 and ‘remitted the amount through Man Chuen, a peal shop in Canton’. They received 32 pound from ‘Man Chuen On store in Cooktown’. However, his father was sick again and all the back-home money was spent on his father’s treatment. After See Poy saved money from his restaurant job, he asked his father if he could return to China again but his father refused his request and used the money invested in a ‘vegetable garden with a few of pigs in it’. ‘There followed a drought; the vegetables withered and the pigs all died’. His father ‘gave up the whole venture and went again digging for gold’. At the end, they abandoned the garden. See Poy moved to Johnson River Velley when he saw ‘some Englishmen advertised for labours’ in March 1882. This ended See Poy’s gold dream in Palmer.

In the peak time of Palmer gold field, there were over 10,000 Chinese but not all of them were digging gold, about half of them grew vegetables, cooked meals and conducted other services like Kwong Sue Duk, the herbalist.

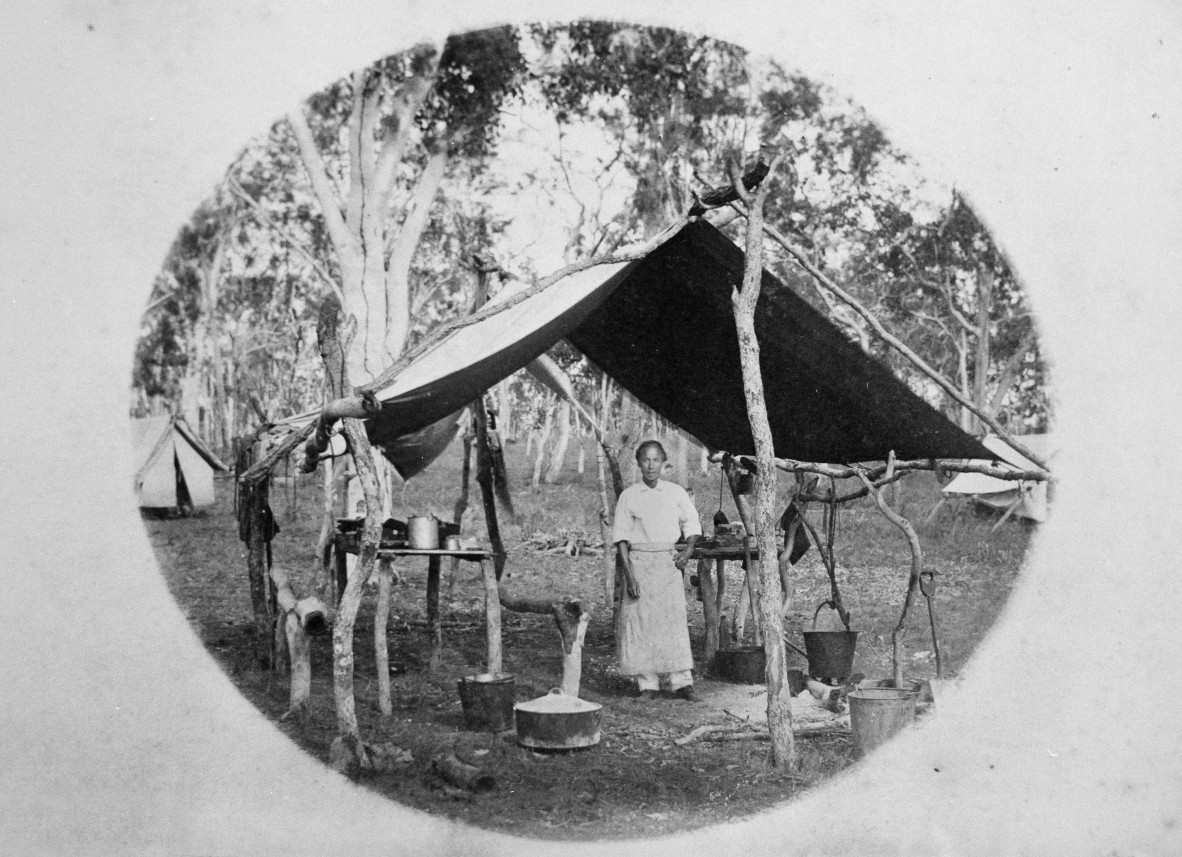

Chinese cook working in the temporary kitchen of a surveyor's camp, 1886

Kwong Sue Duk had totally different life experience with See Poy. He went to California in his teens and made his first bucket of gold. In 1874, he came back to China and learnt herbal medicine. One year later (1875), he came to Cooktown and set up a business selling tools and supplies to Chinese gold diggers. In 1879, when the gold rush in Palmer retreated he returned to China and came back to Australia in 1882. This time, he set up a business called ‘Sun Mow Loong’ in Southport NT (near Darwin) selling general goods and real estate. With the booming Chinese population in Southport and surrounding goldfields, Kwong’s business had a turnover in trade of £25,000 per year. (At the similar time, See Poy saved £25 a year working in a restaurant).

In 1877, the Queensland government passed “The Chinese Immigrants Regulation Act”. Chinese started leaving palmer gold field for Cairns.

In 1878, the famous “Chinese Question AD” was published on the 5 August by Chinese community leaders to improve the understanding between Chinese and other Australians.

During this period, there were the Second Opium War (1856-1860) and the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) in China. The Beijing Agreement signed in 1860 opened more ports in China and legalised the British opium trade in China. At the same time, the Taiping Rebellion created a period of radical political and religious upheaval. An estimated 20 million Chinese people were killed during this period. More Chinese people became opium addictive and more people were looking for new hope. Gold rush to California (Jiu Jin Shan) and Melbourne (Xin Jin Shan) became very attractive. These explained why there were so many Chinese people came to Australia.

In 1881, the Chinese population in QLD reached the peak. Over 11,000 Chinese people lived in QLD.

In 1882, Tom See Poy moved to Innisfail and Kwong Sue Duk moved to Southport in Northern Territory, a thriving river port during the Pine Creek gold rush near Darwin, and set up his store Sun Mow Loong.

This marked the end of the gold rush in QLD.

At this stage, most Chinese businesses in Queensland were in Cooktown importing goods from China to supply Chinese miners and offering accommodation and other services. There were some small vegetable gardeners in Palmer gold field as well. Andrew Leon set up Hap Wah plantation Company, the first Sugar growing venture in Cairns.

Merchants in the Darling Downs, ca. 1875

Discover More

To help understand the historical background and the social background of Chinese business in Queensland I created this chronological overview of Chinese business in Queensland online using the time graphics platform.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.