The Bully of the World: The Queensland Press and Germany August 1914 – April 1915

By JOL Admin | 3 December 2018

Guest blogger: Dr Martin Kerby, 2018 QANZAC100 Fellow.

During the first nine months of the conflict the Queensland press communicated an imagining of the conflict framed by binary opposites. The contrast between peace and war, patriotism and a fervour for war, the societal roles of males and females, and German militarism and Pax Britannica, were the tools by which the conflict was explained and understood. Central to this process was an unrelenting demonization of Germany wherein the war was portrayed as one waged for civilization and on whose outcome rested the future of mankind.

This was particularly important in the Australian context. Far removed from the scene of battle, Australians manufactured threats and crises to make the war real and immediate.1 The oft repeated claim that Australia was to be the first prize claimed by a victorious Germany was only one of the symptoms of this desire to imagine the war as a series of binary opposites. This demonization of Germany was underpinned by a criticism of German war aims, which were venal, and their method of waging war, which was barbaric.

The Germans – why they fought

Though German war guilt remains a highly contentious issue, in 1914 the Queensland press stood ready to play judge, jury and executioner. The evidence that Germany deliberately provoked the war was “overwhelming" (The Queenslander, 22 August 1914). The implications were equally clear:

The German Empire on its present basis and with its present aspirations is obnoxious to the peace of the Western World and the tranquillity of the Orient. Either its dream of universal power must be shattered, or all other nations must prepare their necks for the yoke. (The Queenslander, 22 August 1914)

For two decades Germany had been the “scourge of the civilised world, flogging her great neighbours as with a whip of scorpions into colossal expenditure on naval and military armament” (Telegraph, 24 August 1914). In contrast, history showed that Britain always “fought for the right” (Dalby Herald, 26 August 1914). The press found ample proof of German ambition, which was nothing short of “Satanic” (The Queenslander, 7 November 1914). For in the “ferment in South Africa, Turkey, Afghanistan, Egypt and China sinister hand is traceable”. Making it real and immediate for Queensland readers required the additional warning that “if their results are answerable to their efforts the dismal business of destruction and slaughter will have many ghastly branch establishments” (The Queenslander, 7 November 1914). For those readers in doubt as to the implications for Australia, they need look no further than Germany’s “lust for arrogant supremacy” which was “deluging Europe with blood” (The Queenslander, 3 October 1914).

It was not sufficient for the press to excoriate the Germans for their desire for war. This needed to be contrasted with its binary opposite - the “righteousness of cause which has compelled the British Empire as one man to take up arms in defence of the right, and our own health and home” (Beaudesert Times, 14 September 1914). Though German power was an existential threat, the world was in fact made safer by the fact that a “huge power for good or ill is destined to rest with Britain and not with the nations that would use it to enslave humanity” (Beaudesert Times, 25 September 1914). Germany was the “bully of the world” (The Queenslander, 9 January 1915). In contrast, Britain was “the bulwark and mainstay on the side of peace, her matchless strength, her absolute sense of right, and her determination to oppose whatever is wrong, inspire all nations with confidence in her” (The Telegraph, 4 August 1914). Often the war required considerable cognitive dissonance, for in this construct German ambition would be thwarted by the “greatest Empire the world has ever seen, and on which the sun never sets” (Dalby Herald, 26 August 1914). Indeed, to protect the neutrality of Denmark and Holland, it might be necessary for the Triple Entente “to take possession of them” (The Queenslander, 22 August 1914).

The Germans – how they fought

The demonization of Germany as the binary opposite of civilized values is no more obvious than in the regular and often very detailed descriptions of German atrocities in Belgium. Official reports naturally emphasised the brutality of the German as part of wider efforts to portray the war as a clash of world views, one civilized and cultured, the other barbaric and brutal. What they lacked in accuracy they made up for in detail. By the second week of the war atrocity stories were a regular feature of the news from the Western Front, with The Queenslander’s approach a case in point: the execution of a priest among other “serious outrages” (22 August 1914), “arrogant brutality”, “rapacity”, “military barbarism” (29 August 1914), burning churches, shooting priests, raping girls and women, taking hostages, cutting the ears off children (19 September 1914), forcing a women to drink the blood of her murdered son (3 October 1914), bombing a Red Cross vessel, shooting civilians, mistreating British POWs (24 October 1914) and amputating children’s hands (31 October 1914). In short, it was widely accepted that the passage of the German army across civilian territory in August and September 1914 had been marked by “violence, pillage, conflagrations, and murder” (27 March 1915).

The bombing of Antwerp by a Zeppelin was the subject of particular criticism, for had the crew of the airship and the military that sent it “been in conclave with the devil and his angels there conduct is so diabolical that it could not be worse” (Telegraph, 28 August 1914). War brought out all that was bestial in German nature, but for Australians “all the best qualities of our British race have been shown in the national outburst of loyalty in the breaking of all fictitious differences, and in the glory of manhood, the one bond of race making all stand shoulder to shoulder against a common enemy” (The Queenslander, 29 August 1914). “The Empire’s peril” he believed “had united everybody under one universal sentiment, namely, that of combining to defeat the despotic aims of the military oligarchs of Europe” (Bundaberg Mail, 10 August 1914).

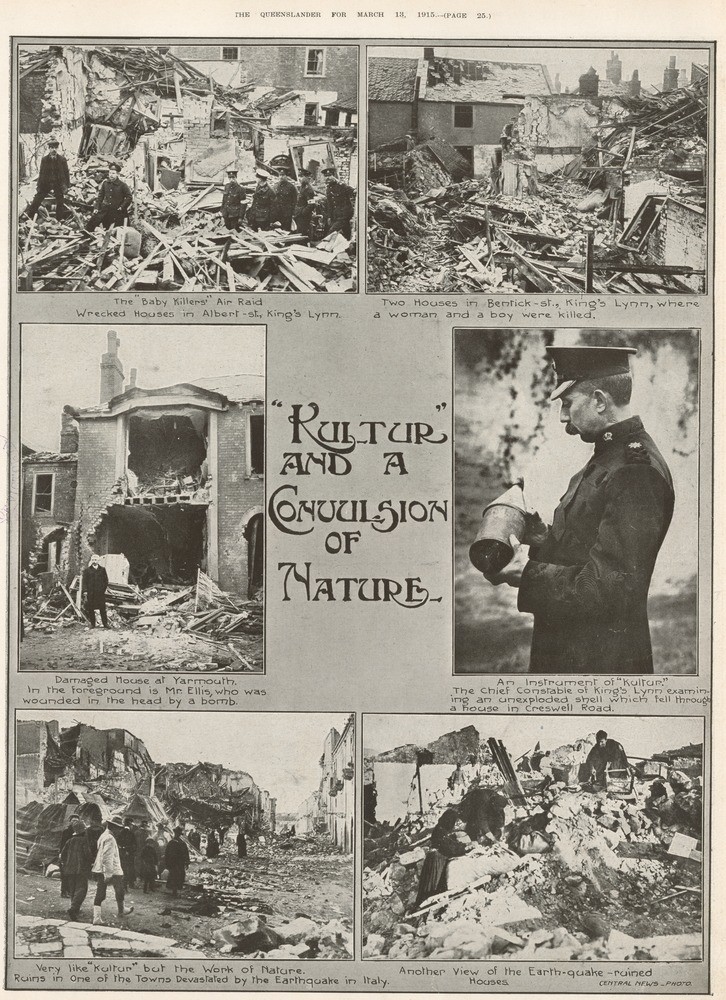

It was not just words that were employed to eviscerate the Germans. In mid-March 1915 The Queenslander ran a series of pictures showing the devastation caused by German air raids and naval shelling on British towns. Though area bombing was still a generation away, the reference to the "baby killers’ air raid" and the designation of an unexploded shell as “an instrument of Kultur” made it clear that it was a war against barbarism (13 March 1915). On the occasion of the Kaiser’s birthday in 1914 a clash between British and German ships led one journalist to describe this shelling of English coastal towns as proof that “the laws of warfare do not weigh with the super men of Germany” and further speculating that the German Navy would have preferred to celebrate the Kaiser’s birthday “with a baby killing excursion” (Beaudesert Times, 5 February 1915).

The demonization of Germany was problematized by the presence of 100,000 German Australians. In time, some 7,000 of them would be interned amidst a general anti-German hysteria, though during the early months of the war before Australians troops were committed to battle, some press reports cautioned about such an intrusion on the domestic front. At a patriotic demonstration in Warwick, a local alderman delivered a “rousing address” during which he “urged the crowd to in no way molest or insult German residents in their midst” (The Bundaberg Mail, 11 August 1914). At another gathering, one speaker argued that though the position of the Empire was “perfectly clear and honest”, there should be tolerance for the Germans in their midst, “who were of a very high type”. It was not, as he reminded his audience, a “people’s war”. It had been “forced by a dominant military party” (Beaudesert Times, 21 August 1914).

Very quickly, however, the tone changed. The Dalby Herald reminded German Australians that “war is not a kid-gloves business”. They needed to “recognise that Australia is an integral and intensely patriotic party of the British Empire” and though they may “often feel pained at what appears in the Press they may doubt the accuracy of it they must admit its legitimacy in such a time” . The real drive of the article is to be found in the observation that Australians must recognise that their “kith and kin … are dying on the battlefield, and that no matter how loyal these settlers determine to be they must view the struggle with very mixed feelings” (17 October 1914). By December 1914 it was possible for a reader to be advised to “run … down, chase him to earth, treat him as you would a dingo, clout him over th head … show him no quarter” (The Queenslander, 9 January 1915).

The government and the press was in the vanguard of this process of demonization, which progressively became more virulently racist from 1915 onward, spurred on that year by the first use of chlorine gas at Ypres on 22 April, the landing on Gallipoli on 25 April, the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May, and the release of the Bryce Report into German atrocities on 12 May.

Conclusion – reaping the world wind

Within weeks of the outbreak of war, it was already an article of faith that in Queensland “all the best qualities of our British race have been shown in the national outburst of loyalty in the breaking of all fictitious differences, and in the glory of manhood, the one bond of race making all stand shoulder to shoulder against a common enemy” (The Queenslander, 29 August 1914). In contrast, however, by war’s end Queensland was derided as a “hotbed of disloyalty” and the “arch home of everything anti-Empire and anti-Australian”.2 A society now well used to dealing in binary opposites was fertile ground for the looming clash between the opposing forces in a divided society.

1 Raymond Evans, Loyalty and disloyalty: social conflict on the Queensland homefront, 1914-18 (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1987).

2 Raymond Evans, A History of Queensland (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 159.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.