Brisbane concentration camps and the White City

By Stephanie Ryan | 19 January 2015

The Queensland Times newspaper’s regular correspondent who visited and reported on the Enoggera Army Camp during World War One, referred to it as the Enoggera concentration camps. Why? It did not fit our common definition of such a camp, where prisoners of war were forcibly detained in awful conditions. It was because of the many servicemen concentrated in training camps; more than a small city such as Brisbane was used to. A number around 10,500, which would include some very energetic men tired of the tedium of war preparation, could unleash mayhem on Brisbane’s tiny centre. This led the way to the White City.

Enoggera Concentration Camps, The Queensland Times, 24 January 1916, p.6

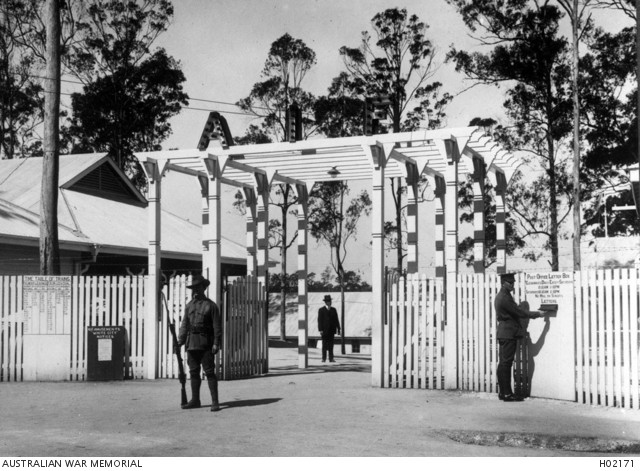

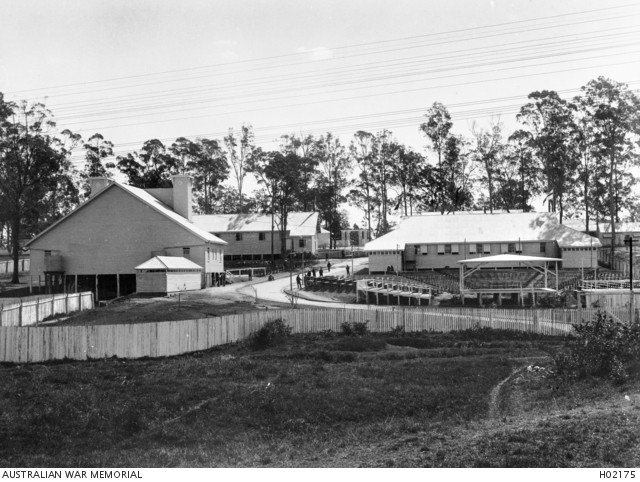

The White City was an entertainment precinct, north of Browns Dip Road, established in 1915 at a cost of £10,000, acquired from a previous canteen and recreation centre. Soldiers, their families and friends as well as, at times, the general public, could use it. The term, “white city” has been used in relation to buildings such as those at the Chicago and London world exhibitions, entertainment provided in groups of tents or even a tennis centre. Here it applied to a number of buildings including a boxing stadium, billiard room, bandstand, theatre, restaurant and soda fountain on the camp base. The newspapers regularly reported on, and promoted, events there. Distributed flyers kept everyone aware of its programs. As a result, we get an insight into how the community supported servicemen during the war, as well as the conveniences of life, tastes and treats of another era.

Entrance to the White City Training Camp, Enoggera Barracks, c1915. Image courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, accession H02171, photographer unkown.

Various buildings of the White City at Enoggera Army Camp, ca. 1915. Image courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, Accession HO2175, photographer unknown.

White City entertainment

The first major event, announced in the Brisbane Courier on 20 January 1916, was the official opening of the boxing stadium on that day, attended by local and military dignitaries. White City was usually on the itinerary of anyone of importance, and was a point of local and national military pride. Boxing was sufficiently popular to attract Les Darcy as a starring attraction. In February 1916, the Brisbane Girls Club, one of the many associations raising funds for the war effort active in assisting this precinct, presented a piano and a billiard table for the White City, accompanied by a concert. The Brisbane Courier provided the train timetable for the event and reminded Sandgate attendees that they would need to change trains at Mayne Junction (Bowen Hills). Private car travel was still rare.

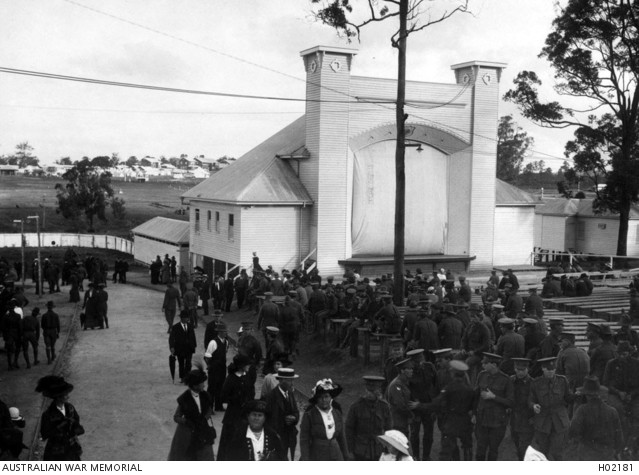

Theatre with exterior stage at the White City, ca. 1915. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial. Accession: H02181, photographer unknown

The Brisbane Players’ Dramatic Club staged comedies. The Battalion Bands played waltzes and sweet English songs as well as marches. The City Ladies Miniature Rifle Club organised concerts that sustained the upbeat tone with numbers such as Cheero and The Bubble Song. In 1916 the Rev Dr Merrington delivered his Anzac Day lecture there. A photoplay, Peg of the Ring, conjurers and other diversions packed the theatre cinema. On 1 July 1916, the Queenslander published a full page of photographs of White City.

A powerhouse was erected on the grounds. The soda fountain, providing a variety of flavours, was run by electricity, which was still a novelty. Alcohol was not on the White City menu. Evening concerts were enhanced by electric light, with light bulbs draped from the trees to provide a fairy-like ambience. The restaurant, open from 9:30am-9:30pm, served a mixed grill.

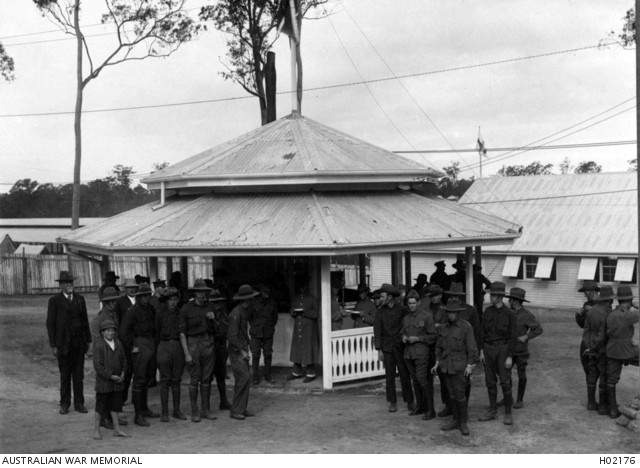

Refreshment booth, White City, Enoggera Army Barracks. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial, Accession H02176, photographer unknown.

Soldiers’ thoughts

Soldiers wrote home about the complex. The 'Western Champion' reported that Bob Whyte had caught up with an old comrade from Cork at White City. The Queensland Times reporter gave an account of soldiers from Ipswich he met there. Private Fenwick was quoted in the ‘Mareeba Notes’ of the Cairns Post (6 December 1916), listing the attractions and expressing his enthusiasm thus: “They were spending £200 a month on the White City but it was worth it. It kept the men in camp instead of going in the town. It wasn’t only amusements but knowledge and edifying things”. Another soldier saw it as part of boosting camaraderie.

Popularity of the White City

By January 1917, the Queensland Times reporter, usually so impressed by the White City, commented on “the want of animation”. He reiterated this in April and raised the issue of “the small number of soldiers” affecting the range of entertainment provided. Nevertheless, the associations supporting soldiers continued to do so. By the beginning of 1918, the White City, together with enthusiasm for the war, was fading.

The heyday of the White City was 1916. It contained and entertained large numbers of soldiers, as well as providing some of the recreational delights resulting from electrical power. It was a welcome relief from the backdrop of war, and demonstrated community support for the soldiers. The Bulletin of 10 August 1916 published a verse by Mabel Forrest about the White City, capturing some of this spirit. It concluded with the lines:

“Twinkling an invitation down the night / A silver call of bells to carnival.”

The White City mirrored sentiment about the war and was closed at the end of it. Facilities were then auctioned.

Stephanie Ryan, Senior Librarian Family History, Information Services

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.