black&write! session at 2017 IPEd Brisbane conference: Editing work with Indigenous content

By Grace Lucas-pennington | 7 November 2017

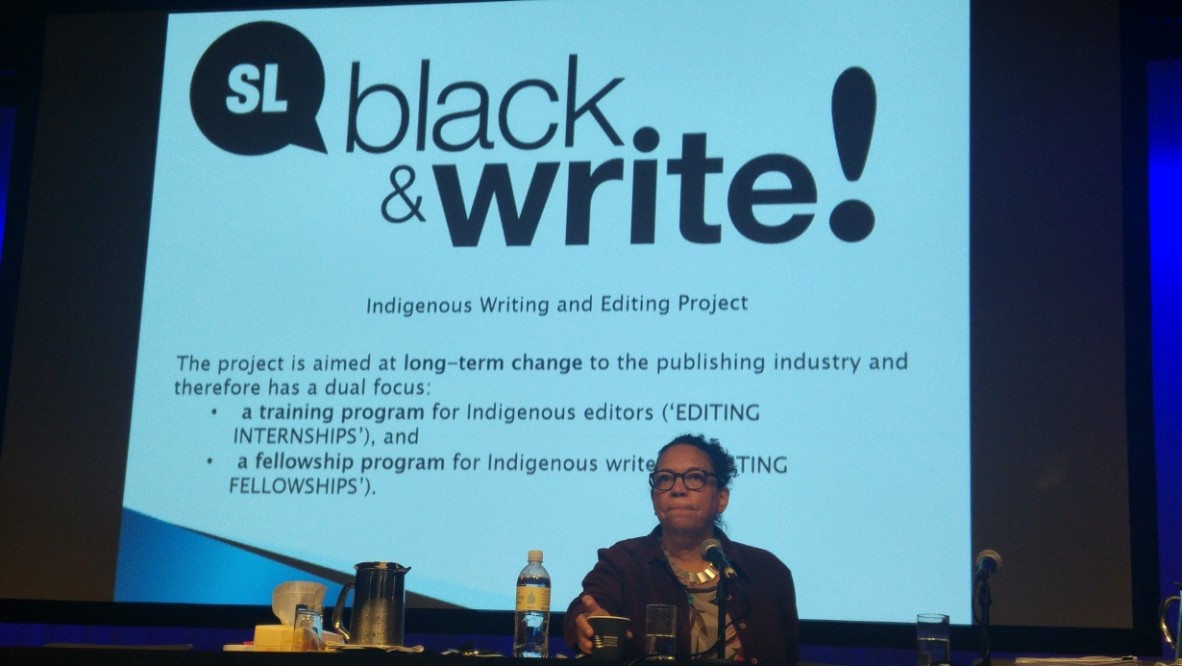

The Institute of Professional Editors (IPEd) is the peak body for editing professionals in Australia, and they recently held a national conference at the Brisbane Convention & Exhibition Centre. We had the opportunity to work with the national IPEd conference, so black&write! presents to you our session from that day; In Conversation between Dr Sandra Phillips and Grace Lucas-Pennington representing black&write! Project, on the topic of Editing work with Indigenous content.

Speaker bios

Dr Sandra R. Phillips was an inaugural judge of the black&write! Fellowship and continues a relationship with the project. black&write! recruits, trains and mentors Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander editors to develop Indigenous-authored manuscripts. black&write! is made up of the Indigenous Writing Fellowships and the Indigenous Editing Internships. Dr Phillips is an academic and researcher with QUT Creative Industries in its School of Communication lecturing in editing, publishing, professional communication and Indigenous Knowledges. Current elected Chair of the First Nations Australia Writers Network Inc. (FNAWN), Dr Phillips trained as a book editor with Magabala Books and UQP, later becoming the first Aboriginal person to manage Aboriginal Studies Press. Sandra went on to complete, with her current Faculty, a PhD into Indigenous authoring and publishing, and readership of Indigenous-authored texts. Dr Phillips’ First Nations include Wakka Wakka and Gooreng Gooreng.

Grace Lucas-Pennington is a young Aboriginal woman of Bundjalung/European descent. Growing up, she spent her time between Northern NSW and the Logan/Brisbane area. Grace is interested in publishing, politics, media, social justice, and the arts. She is passionate about First Nations writing, and promoting our stories. Grace currently has a position with the black&write! Indigenous Writing and Editing Project as Editor.

Transcript(edited for on-screen reading flow. Transcript by Hella Ibrahim.)Dr Sandra R. Phillips (left) and Grace Lucas-Pennington (right)

Transcript

(edited for on-screen reading flow. Transcript by Hella Ibrahim.)

Dr Sandra R. Phillips (left) and Grace Lucas-Pennington (right)

Grace Lucas-Pennington: What are the benefits of Indigenous writers and editors working together?

Dr Sandra Phillips: We all know a good story is built from not just the plot, not just the characters, not just the settings and not just the literary frameworks. It’s also built from the small details. So the benefits of taking that as an analogy, from the question that Grace posed around Indigenous writers working with Indigenous editors, is that you get this cumulative layering of respectful, baseline insight as to where each other is coming from around all of those small details so that energies are actually invested in the build, as opposed to the questions that are on the page to start with.

You’ve got, if not a complete fit, a more adequate fit between an understanding of the world, what is considered important through an Indigenous world-view, what some of those common shared stories are. Uncle here today had a biography about me for a mainstream audience and I had to supplement that with what we in our Indigenous discourse privilege, which is, Who are you? and Where are you from? Who are you related to? Which then locates me in relation to Uncle and other Aboriginal Elders. It’s pertinent because I could be any old one. I could be anyone sitting up here saying these things, but when it comes to Indigenous story and cultural sharing we need to think about who each other is.

Elder Uncle Joe Kirk at the 2017 IPEd conference Photo Credit © IPEd Conference 2017

GRACE: And that’s about trust, really, at the heart of it. At the editing level, not to say it’s impossible with a non-Indigenous editor, it’s just easier…

DR PHILLIPS: Yeah exactly. The trust every editor already knows that’s part of the strain of an editing relationship and at QUT, where I work in Creative Industries, I refer to editing as an act of diplomacy. So we are all ambassadors for good writing, for literature, for story-telling and I’m sure that professionally those ethics of care, of concern and recognising always that the author is the creator of the work. Our role, as Charlotte Wood said several years ago when she won the Beatrice Davis Fellowship, is to make the writing the best it can be and to fill that gap or any gap there might be – to help the writer to fill those gaps.

I think that there’s a lot of our personal way involved in all editing processes, so if you understand that your way of doing things is relevant to editing, you have to then go that next step of who you are, where you come from culturally and how you view the world is also part of that lens and that process.

Dr Sandra Phillips

GRACE: We talked about working with Indigenous authors but there’s also the issues of being an Indigenous writer or a non-Indigenous writer, writing with Indigenous cultural content included, so what is that? What do we mean by that?

DR PHILLIPS: I’m not real keen on binaries and dichotomies, but I am going to enforce one at the moment just for the sake of brevity.

Indigenous cultural content can be that which is long-standing millennial knowledge that predated British invasion and colonisation, so those stories that relate to our creation, creation of the land and our worlds both physical and metaphysical.

That’s the first half of the binary which is only functional to a limited extent but bear with me. The other aspects of Indigenous cultural content that we’re talking about relates to what I’ve called Shared Histories following Invasion.

The first part of the binary is essentially hands-off (or enormous care and protocol clearance) for everyone, it’s equally as problematic for Indigenous creative writers to dwell in that space as it is non-Indigenous.

GRACE: Can you say why it might be problematic?

DR PHILLIPS: It is problematic because those stories belong to certain territories and the custodians of those territories. Those stories of antiquity hold standing in light of that which other religions hold, so in descriptive terms, secondarily but equally importantly as custodians of those stories pertinent to particular territories people are responsible for those stories being treated appropriately. It’s not public knowledge, it’s not for everyone to play with. As Alexis Wright spoke about in Angel’s Palace (BWF 2017) on the weekend, if you’re a custodian of a story and someone messes with that story, you could get sick – it’s corporeal, it’s actually real and bodily and it relates to the here-and-now as well as the antiquity.

When it comes to what happened after the British invaded and colonised our nations, or at least attempted to colonise our nations, there are stories within that which I see non-Indigenous writers and non-Indigenous editors building competency in relation to. Because of those stories being shared histories and shared stories, but – I’m deliberately using the words colonisation and invasion, if that’s making people uncomfortable I suggest that you don’t edit writing that involves facing the fact that our nations were invaded and that for the most part you’re all descendants of the people who gained privilege out of that invasion. If that makes you uncomfortable, don’t edit Indigenous writers.

GRACE: How can you tell if a writer is using Indigenous themes or content in an appropriate manner?

DR PHILLIPS: It goes back to nuance and detail. Sometimes people can pull it off really well; we won’t name names, we won’t refer to some of the past scandals, we won’t bring that too much into the conversation. But sometimes people can pull it off, they can see the vernacular that Indigenous writers use, they can see the shades, the tones, the subject matter. You can actually pull it off and fool people which I’m not promoting but I’m just saying that it’s possible to do so there are characteristics.

The next step from understanding is that there are certain characteristics of Indigenous writing that signpost the richness of the work. Sometimes people can’t pull it off but they still sell hundreds of thousands of books in the United States because their readership is largely ignorant and captive to those discourses of exoticism and primitivism and wanting to believe things about the First Peoples of any colonised continent or country. So you can tell, the majority of the time you can tell, and it is around the cumulative impact of thousands of small details.

GRACE: Whose responsibility is it to ensure that the work meets a basic level of cultural competency or ethical standard for publishing? Is it the author? Is it the editor? Is it the publisher?

DR PHILLIPS: Great question. The easy answer is everyone. And I would add in there of course that the Australia Council has published and revised guidelines, protocol kits, that in some way tangentially influences their funding decisions so in some ways we’ve got a bit of a landscape where it’s generally understood that if a writer hasn’t pursued appropriate protocol clearances on particular matter then they’re not necessarily worthy of being funded through the public purse.

That said, having sat at the table during some of those discussions, there are no criteria that go with that so it’s this kind of general understanding and general ethics and commitment but it’s not something people can be marked down on or marked up on. So all change is slow and everything is in constant iteration. I’m flagging the funding bodies, the authors… the creative process as we know is an incredibly complex one but once again taking the long-term view of things, creative writers are not geniuses unto themselves – creative non-fiction as well, non-fiction technical writers.

The West promulgates this view that a writer is a unique being and that what they’ve created is not welded, is not connected to, the world because it’s come out of their genius. I do not subscribe to that view whatsoever and I think that editors are part of the process of ensuring appropriateness in creativity. We quality control every other element of a published work, why can’t a professional editor also be part of the quality control on the richness and nuance around appropriate representation?

Audience question: I don’t deal with fiction editing at all but I’ve been editing in educational publishing for many years. Our biggest issue is maintaining that appropriateness in the non-fiction stuff that we publish. The current Queensland syllabus has a strong emphasis on including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives across all areas of the curriculum, so when we get the material from the writers who are largely not Indigenous writers and it’s being edited by largely not Indigenous editors we would really like some specific guidelines and training in that appropriateness. Because by sheer numbers the people who are editing Indigenous content are going to be often non-Indigenous people. How do we go about ensuring that?

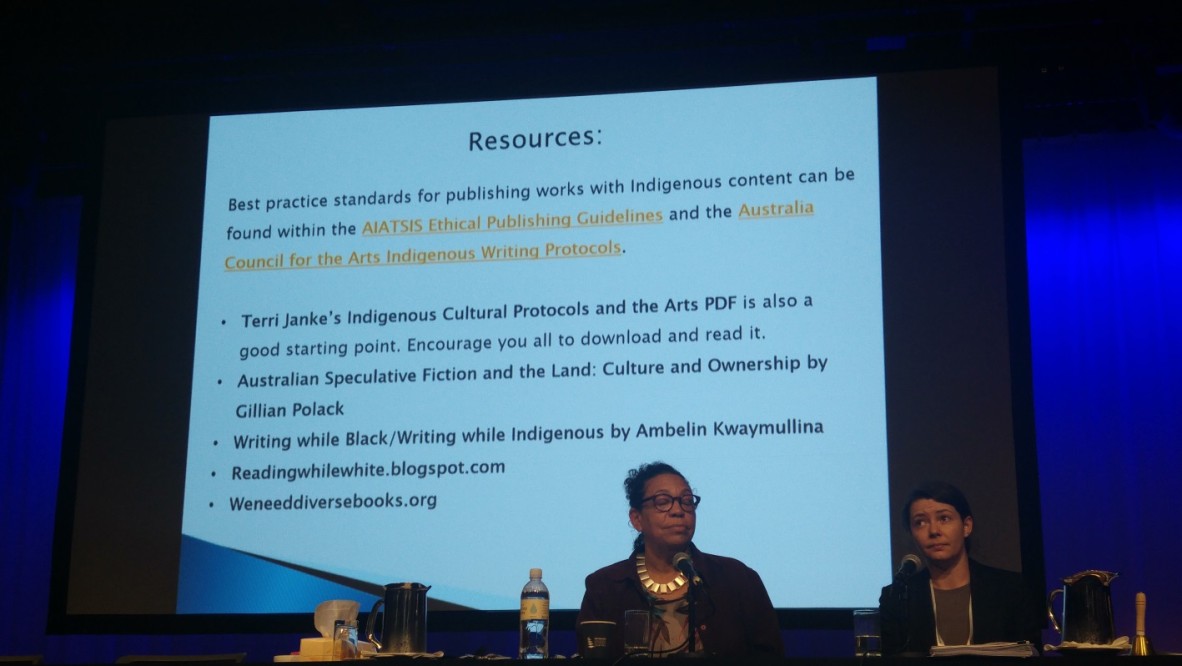

DR PHILLIPS: Thank you for that question. Grace will navigate to a slide that she has created with some links to guides that are already in circulation, have been for a long time that you might find useful.

Suggested resources compiled by Grace Lucas-Pennington

I encourage you to search for Indigenous professional associations and approach them directly on any advice they might be able to offer you. Clearly educational publishing – as Craig Munro and Robyn Sheahan-Bright wrote in Paper Empires, educational publishing took Australian publishing out from under the coat-tails of British publishing but then educational publishing continues to be a huge part of the market and a huge opportunity for Indigenous writers to be facilitated, to take advantage of those opportunities in relation to national curriculum about their voices.

Audience question: I need some advice, as an editor whose background is known across a broad spectrum. I often get enquiries from non-Indigenous writers who are writing Indigenous content. I got quite an interesting one recently who I advised to think very seriously about what he’s doing. It’s a work of fiction that draws on post-invasion cultural breakdown, drawing on pre-invasion traditional cultural practice to try to solve problems through a very spiritual way, and I afforded him Alexis Wright’s recent, quite long, essay on this topic and told him to have a think. He still wants to go ahead and said that the original story came from his experience in Canada and he’s translating that over and he thinks he can do it. I advised that maybe he could find an Indigenous writer as a mentor, perhaps Alexis, perhaps your good self. What further can I do? Should I dissuade this guy or help him by connecting him with the right people?

DR PHILLIPS: Great question Kerry. At one of the sessions at the Brisbane Writers Festival, Alexis Wright herself, Nakkiah Lui (a playwright, screen writer and actor), and myself we were on a panel looking at Aboriginal perspective in writing and the two questions from the floor were the same questions. And it’s the same question: I am doing this or I want to do it and how best can I do it? So we know in Australia we have a big problem with extractive industries, right. I call that another extractive industry. It’s trying to mine Aboriginal cultural knowledge cultural perspective, mine the post-invasion on the binary, mine…

GRACE: mine Aboriginal experience altogether.

DR PHILLIPS: and it would be a very rare non-Indigenous Australian writer who could pull it off well. So my equal concern has always been around the reading and reception of the work so that we can raise the bar, so we don’t see another Marlo Morgan.

We need to raise the bar as all practitioners in Australian literary culture around what is… what works and doesn’t work.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.