- Home

- The Story Bridge essay by Julie Hornibrook

/

The Story Bridge essay by Julie Hornibrook

The Story Bridge is iconic to Brisbane and its identity. It’s brave, bold, historic and ever present. It was completed during WWII and did us proud in the war as infrastructure to support rapid movement of troops. It graces the skyline of Brisbane images as Queensland’s capital city.

The Bridge was built from a visionary concept and design. It needed energy and innovation to achieve the results and build confidence for the town. The Bridge fashions imagination to this day, lit up in various colours to celebrate Brisbane’s moods and seasons of celebrations. As Jennifer Stuerzl, quotes in ‘The River (58)1,

… river crossings are the most evocative city journeys made in Brisbane. In straightforward terms their history is the connecting of the River’s northern and southern banks. But in their significance, River crossings are traced by human aspirations .

Hence, the Story Bridge, its 12,000 tonnes of steel and capacity is also about stories of the people who built it, believed in it and believed in building Brisbane.

The Courier Mail 2 on July 6, 1990, notes three names associated with the Story Bridge – Bradfield, Story & Hornibrook. Manuel Richard (known as ‘MR’) Hornibrook was my grandfather, a man of his time and just the right figure to take on the building project with his brothers in the family business, working with the expertise of the engineer, John Bradfield, and supported by a government keen to grow and invest in Queensland building projects in the tough years of the Depression.

So much of the story of the Story Bridge has been documented, told and re-told in this 75th anniversary year. The John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, has a blog in pictures of the building of the Bridge. The Bridge is iconic and lives in the hearts and minds of modern Brisbane, these days with LED lighting to show it is festive and modern as well as being a link to the past. With bridge climbs, it is more beautiful and accessible than ever and is like the grandfather of all the sixteen bridges that now cross the River. In 1990 a poster celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Story Bridge quipped (6th July, 1990) 2

there’s 2 things you’ll always come across – Brisbane’s most famous bridge and Australia’s most famous beer.

Now the Bridge is classified under the Queensland Heritage Act as an historic monument and will be preserved into the future. The Institution of Engineers Australia also dedicated an Historic Heritage Marker to the Bridge in 1988.

This essay will focus on the role played by MR Hornibrook, the Brisbane bridge builder, who later became Sir Manuel (knighted in 1960). He was highly respected and a builder of bridges across Queensland, NSW, Victoria, South Australia and Papua New Guinea as well as other major projects including Stages 2 (the Sails) and 3, of the Sydney Opera House. The next two essays will focus on the building of the Hornibrook Highway and the Grey St/William Jolly Bridges as two major construction projects that are also iconic in the history and life of Brisbane.

To tender for the Story Bridge, a consortium of Evans Deakin-Hornibrook Constructions was formed. Evans – Deakin supplied the steel and set up a works area at Rocklea and MR took on the building and brought the workforce and skills to achieve the outcomes, working with John Bradfield who was the prominent chief engineer for the Bridge. Bradfield, at age 66, came to Brisbane for the project, after completing his role as chief engineer for the Sydney Harbour Bridge. As a young man in his 30s, MR had completed the building of the William Jolly Bridge in 1932, the Hornibrook Highway (the longest bridge in the southern hemisphere) in 1935 and then onto the Story Bridge project commencing the same year. These three visionary building projects in a decade required determination, innovation and tireless work to achieve.

MR was also a local family man with a wife and four children. They lived at Sandgate for the building of the Highway and the family home was at Ascot. MR was civic minded and involved in supporting the development of the Royal Queensland Golf Club, built the Hamilton Bowls Club and was later involved in various local projects through Rotary including International House at Queensland University. He was a tall, solid man with an earthy approach to life and he became a beacon of strength as a Queensland man who would help lead us through the Depression and build Queensland’s business reputation on a world scale. In 1950, The Bulletin featured a story about MR, saying,

… herewith part of the 17 stone odd of a big man in a big business – MR Hornibrook, who can fairly lay claim to being the biggest contractor in Queensland. (Browne, 133) 3

Background

The tender for the Bridge was no giveaway and when awarded the builders were required to commit to a deposit £50,000 as security for due performance. No sub-letting was allowed (hence the Consortium of Evans Deakin-Hornibrook) and they had to start work immediately. The Consortium won the quote with the lowest bid of £1,150,000. Bradfield was to oversight the project, providing plans and supervising details (Moy). In 1934 the Bureau of Industry approved Bradfield’s recommendation of construction of a steel cantilever bridge. Bradfield described the design of the Bridge as having

sturdy shoulders with graceful curves …best harmonise with the picturesque and rugged beauty of Brisbane’s skyline. (Moy,15) 4

The Bridge was completed in 5 years and in that time Australia joined WW11 in September 1939. All round there was great pride in the excellence and achievement at the opening on 6th July 1940.

The Bridge was initially called the Brisbane River Bridge. When the first sod was turned, the Premier, William Forgan Smith, called it the 'King George V Silver Jubilee Bridge' and when the King died, it became the King George V Memorial Bridge. In 1937, the Cabinet decided to name the Bridge after a veteran public servant and Vice-Chancellor of University of Queensland, John Douglas Story (who seems to have been a modest fellow and it was reported in the press that when this was announced he promptly fainted!). This finally seemed the right name for the Bridge and over time it indeed has many stories to tell!

Newspapers of the day commented that MR made a brief speech at the sod turning ceremony. He gave the Premier a clock and quipped that for every hour that passed over the next four years the government would owe the contractors 33 pounds! He said they appreciated they had won the largest ever tender let in Queensland.

In recognition of the Bridge’s place in the history of Queensland the Courier Mail reported that the Union Jack and Australian flags were buried in a steel casket and laid in the foundations of the pylon at Kangaroo Point ( Courier Mail , 29 May 1935)5.

The Bridge Opening 6 July 1940

The Story Bridge was opened on 6 July 1940 by Sir Leslie Orme Wilson, Governor of Queensland.

The Story Bridge opened to a great fanfare of music and performance and a crowd of 37,000 people– what a big turnout. At a time of the opening this crowd represented more than 10% of the population as Brisbane’s population was about 315,000. The 2015, 75th anniversary celebrations rekindled the fanfare, with markets and open to 60,000 pedestrians to walk across it.

The opening day in 1940 was eventful. During the day, Waveney Browne, Secretary to MR, was the first woman to drive over the Bridge. She would have felt great pride and honour to fulfil this role, however, she got even more colour to her landmark event as her car suffered a flat tyre on the Bridge! She said that tyre was changed in record time, imagine how many helpers would have got the car moving again! (Bartsch,1988)6

A commemorative flag was released and a ‘pop up’ post office on the Bridge so that letters could be stamped with the postmark. Similarly, on the 50th anniversary in 1990 a stamp of the Bridge was also released (City of Brisbane collection, Museum of Brisbane, 2015) and a silver coin minted by the Perth Mint in the Capital Bridges Series.

The opening had some dramas as well. Newspapers reported that both the Anglican and Catholic Archbishops were upset as they had to sit in the hot sun and neither were asked to speak or say a prayer and God was not mentioned in speeches given by the Governor, Sir Leslie Orme Wilson, who opened the Bridge. Perhaps this was in response to previous skirmishes, as noted in the Courier Mail 2, where the Catholics thought the Protestants had been favoured when the Grey St (renamed William Jolly Bridge in 1955) was built near the retail end of town and the Protestants were offended when the Bridge was built near the Valley and the Catholic part of town!

Queensland was immensely proud of building the Story Bridge and boasted that 95% of the construction materials came from Australia and 89% of the cost spent in Queensland. (This was in contrast to the Sydney Harbour Bridge mostly designed by British engineers and built with British steel.) Cement used was from coral deposits at the mouth of river and gravel was dredged from the river. It also symbolised Australia’s evolving identity as an industrialised nation with it’s own capacity to build and resource major infrastructure projects.

The Bridge was the 7th largest bridge of its type in the world at construction and second largest in Australia after Sydney Harbour Bridge (Moy, 57)4. Being heritage listed, the Bridge is constantly maintained to care for the steel and concrete. Now 30 million vehicles cross the bridge per year on 6 lanes. The bridge is 74 metres in height and the overall length is more than 1000 metres.

A story that demonstrates how important the Queensland angle was to the project is told by Moy, who notes that the Bridge is the same design as Montreal Harbour Bridge (also known as Jacques Cartier Bridge), opened in 1930. Before that Bridge was built two bridges had collapsed during building in Quebec. The Bridge engineer, L.R. Wilson, came to Brisbane to advise on the Story Bridge as there were no engineers in Australia who had experience of cantilever bridges at that time. Wilson, however, was not invited to the opening ceremony as the government was emphasising how it was Queensland made and did not want to recognise any foreign expertise!

MR – the builder

By 1960, Contracting and Construction Equipment Journal , (cited in Browne, 70)3 described MR as “one of the greatest bridge builders in the world to-day.” His early building experience and developing the company with his brothers was in Brisbane where he grew up and Browne (60)3 describes at least 25 construction projects along the river built by Hornibrook constructions. She says

The Brisbane River was a river of achievement for Manuel Hornibrook.

The Courier Mail7, 6th July 1940, describes MR as a “man of strong personality and will, a combination which led to a number of clashes with Bradfield who was equally self – determined.” It goes on to say that ‘MR revelled in the complexity of the Bridge design with its enormous foundations & engineering challenges.”In her book Waveney Browne (34)3 notes that Bradfield and MR were good friends and knew each other prior to the Story Bridge project. She describes that they were both used to getting their own way and when Bradfield was asked how he was getting on with MR he replied,

He is perhaps the best contractor in the world but he is also the most headstrong man I have ever met.

All MR’s five brothers joined him in his business (Pearl, his only sister, was not in the business) and no doubt this was part of the strength of the business and the trust within it. However, MR’s character was dominant and he was the main focus, front and centre and the driving leader.

Others consistently made similar comments over time. For example, Sir Raphael Cilento (Chairman of National Trust of Queensland) quoted of MR in the 1960s, (Browne, 129)3 after he had been a founding member of the Trust and a strong supporter: “Sir Manuel’s enterprise and initiative, as well as his confidence, and tenacity, made him a legend in his own lifetime.”

In newspaper clippings from 1935 MR was described as enterprising with reference to his ability to gain the Story Bridge contract. They note his early life and starting the firm in 1912, at age 19, and becoming a proprietary company in 1925. It says few men had undertaken such large contracts in Brisbane. He was 43 years old when he won the contract for the Bridge with Evans-Deakin and had the confidence to bid for it after completing the Grey St Bridge and Hornibrook Highway.

MR worked closely with workers and expected their work to be up to standard. He was known for having an ‘eye like a hawk,’ (Browne, 19)3 and being a craftsman as well as a construction engineer. He could do anything he asked his men to do and wouldn’t ask them to go on a site where he wouldn’t go himself. His nephew, John, cited an anecdote where his uncle had the temerity to toss his hat down to show a Story Bridge worker ‘vibrating concrete’ where he should concentrate his efforts. He mused “He just vibrated the hat into the concrete and it's still down there.” ( Brisbane Times, 11 November 2011).8

The bridge building required innovative work as it was such a unique project for the times. One example was the way foundations were constructed, using strategies developed in constructing the Grey St Bridge. Divers worked underwater up to 40 metres below ground level at the south main pier, which required working under pressure, using airlocks and decompression as workers came back to the surface. Moy (19-21)4 describes this construction strategy in detail, summarising it as “one of the most amazing features of the Story Bridge.”

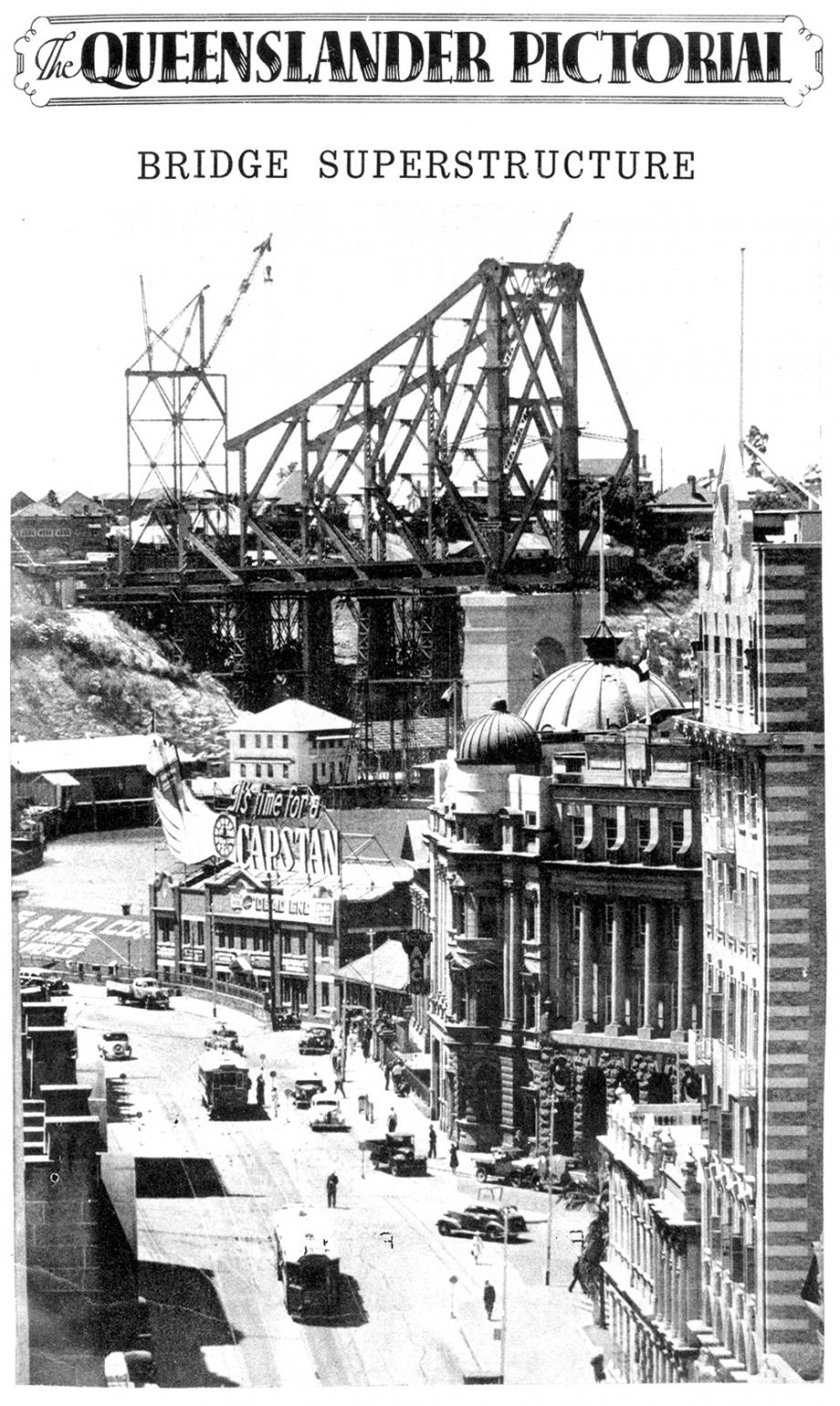

Detail from The Queenslander Pictorial - Bridge Superstructure. The Queenslander, 30 March, 1938

Life in Brisbane

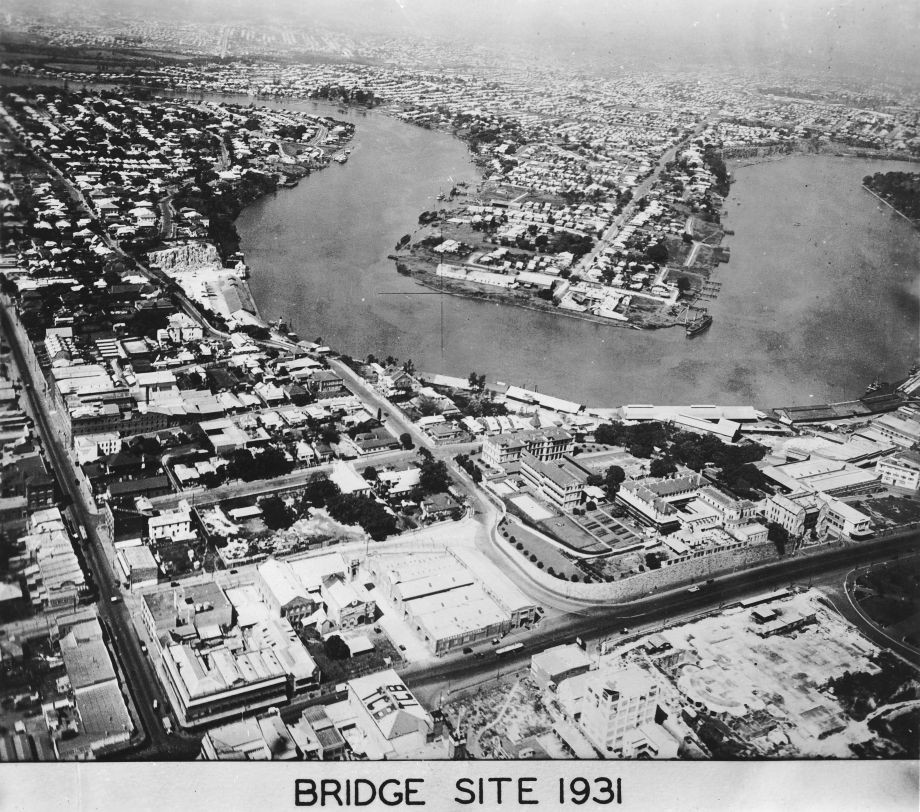

Brisbane became a self-governing colony in 1859. The building of the Story Bridge began only 76 years later, barely three generations and less than 100 years after the first house was built at Kangaroo Point. Queensland was growing quickly, with a population of 50,000 in the 1880s to more than 300,000 in the 1930s. Land was released for sale at Kangaroo Point in the 1840s and all sold by 1854. The horse ferry was started in 1844, to take people and their horses across the river. Before then they took a row boat with a horse swimming along behind, (Queensland Heritage Register)9 . More ferries crossed the river in the 1860s and steam ferry by 1880s. Crossing the river was an obstacle to expansion of the city and commerce – naval stores were by the river, wayfarer’s inns on the south side and retail development on the north side.

Brisbane’s character has been so defined by its river, now described as being central to Brisbane’s identity, (The River, 2015)1. In early settlement of the 1850s the river enabled settlement upstream, ships to bring supplies, increasing trade and movement of people. It also divided north and south and brought many floods as it meandered through the town. The ferries, their jetties and shelters, were vulnerable to floods and regularly washed away, disrupting efforts at more unity.

The Victoria Bridge was the first bridge built across the river in 1865. It was washed away in 1893, collapsed and rebuilt. It was buckling under the weight of traffic in the 1920s and plans were drawn up by Council for a vision of Brisbane with several bridges across the river, including the location for what later became the Story Bridge crossing. The Grey St/William Jolly Bridge was built between 1929 and 1932. Brisbane as a port was growing, as the hinterland of Brisbane was opening up and more commerce, trade and settlement underway. The current Victoria Bridge was built in 1969 by Hornibrook constructions.

The Courier Mail14 8 June 1937, notes that Real Estate Institute Queensland said connecting South Brisbane suburbs with the Valley would open up Camp Hill & Belmont and land was already selling well there. There was local discussion on types of buses and bus routes using the new Story Bridge. Trams were planned initially but didn’t progress into final routes, although trolley buses used the Bridge.

Shipping came up the river to the city and visions for a new big bridge had to be high enough for ships with a 100ft funnel to go underneath. During WWII ships berthed more at Pinkenba and Breakfast Creek for the deep berthing there and some big ships with higher masts wouldn’t get through so the Bridge influenced a shift of shipping closer to the mouth of the river. Once the Bridge was opened the Council considered building wharves at Newstead to better accommodate shipping.

Many old houses were resumed at Kangaroo Point for the building of the Story Bridge. Not all were happy about that but the progress rolled on, transforming the area from it’s more rural outlook. Initially resumptions of houses cost loss of rates to Council so they lost revenue and trees were cut down which also upset local residents.

Nonetheless, the building of the Bridge found its way into the culture of Brisbane and inspired songs, poetry and ballads, for example, ‘The ballad of the bridge boys,’ (Story Bridge photo album, John Oxley Library)10. It featured in the Courier Mail news items and on its pictorial cover,

Williams11, in Story Bridge turns 75: World War II, paying 'resentful tolls' and getting over the Great Depression in 1940, quotes Dean Prangley, Royal Historical Society of Queensland President,

Brisbane was a very small fraction of what it is today. The Story Bridge has seen a huge change in the way people live.

Employment

The Bridge employed about 400 workers at it’s peak and part of the intention by the State Government was to support employment during the Depression, along with investment in relocating the University of Queensland to the St Lucia campus and building the Somerset Dam. This was done under a Rehabilitation Policy (1932). The Premier didn’t want to freeze credit or hide money away and wanted to continue to expand Australia (Courier Mail, Monday 8 July 1940)7 . To ensure employment of Queensland labour, preference was given to union members and those who had lived in Queensland for six months. At the opening of the Bridge the Premier said the money had been well spent and the engineers and builders did an excellent job.

The normal working week was 48 hours over 6 days and not easy to get time off. Harry, a worker on the Bridge, couldn’t get time off for his own wedding and had to work a night shift! (Moy, 50)4

Three workers lost their lives on the Bridge construction (a fourth person died in a fall but it seems he was a curious climber on the construction site and not employed). Although a sad loss for the workers and families, given the conditions of the time, it is notable how few lives were lost. Graeme Oliver (Moy, 52)4 said “we never had hard hats, eye protection, ear protection or safety boots. Those things weren’t invented. “It is a testament to the trust and camaraderie of the workforce that they looked out for each other and developed such skills in working on heights. In 1999 a ceremony was held for surviving Bridge workers when the then Brisbane Lord Mayor, Sallyanne Atkinson, made the final payment on the Bridge loan to the State government.

Toll Bridge

The State government borrowed money for the Bridge costs and introduced a toll to assist with loan repayments. Estimates were that in first year only 8% of city traffic would use the Bridge, as the new toll was largely resented by the Brisbane public. Historian Dr Jack Ford notes that “because money was short after the Great Depression the public didn't quite see why they had to pay that toll. That resentment continued because people thought it'd be years before the toll was paid off. But then the war intervened and because the war the Americans arrived. [With] thousands of Americans paying sixpence daily to cross the Bridge, it was paid off by 1947.” (Premium News, 1st July, 2015)12. The toll was also controversial within the Greater Brisbane Council and some through it was shameful that the Council could not afford to pay for its own infrastructure.

The toll was set at 6d/motor car, 3d/horseman motorcycle, 1d/bicycle, 1d/bus passenger and 1d/travelling stock. (6d was twice the price of a newspaper at the time). The toll was abolished when Brisbane City Council purchased the Bridge from the state in 1947 for $1.5 million (which was paid off by the Council in 1989).

It was only with the arrival of American forces in 1941 that the Bridge started to be used near capacity. During the war approximately 1 million American troops were based in Australia and many in Brisbane. General Macarthur was based in Brisbane in 1942 as Supreme Allied Commander, South West Pacific. (Fitzgerald et al, 111)13. There were barracks near Rocklea and troops travelled back and forth across the Bridge to the airport base at Archerfield, a great boon to toll collecting for the Bridge! At that time there was only one car to three civilian families, so the wartime business confirmed the value of the Bridge and helped pay off the loan in rapid time. Some families also moved away from Kangaroo Point, concerned about ‘the Brisbane Line’ and the risk of wartime bombing of the Bridge as a likely target, (Interview Frank Moss, architect Fulton Trotter, Brisbane, 11 August 2015).

References

| 1. Exhibition Museum of Brisbane The River: A history of Brisbane, City of Brisbane collection, August 2015 | 2.The Courier Mail, 6 July,1990 | 3. Browne, W., A Man of Achievement, P.E.P. Enterprises, Brisbane,1974 |

| 4. Moy, M, Story bridge idea to icon, Alpha Orion Press, Brisbane, 2005 | 5. The Courier Mail, 29 May 1935 | 6. Bartsch, Phil. “The flat that defeated the wheels of progress.” The Courier Mail, 22 April 1988 |

| 7. The Courier Mail, Monday, 8 July 1940 | 8. Moore, T. “Brisbane tolls a familiar Story,” Brisbane Times, 11th November, 2011 | 9. Queensland Heritage Register, Queensland Heritage Council, Ferry transport, "Bulimba Ferry Terminal, entry 02211" |

| 10. Story Bridge album, “The ballad of the bridge boys,” Brisbane, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland | 11. Williams, P, Story Bridge turns 75: World War II, paying 'resentful tolls' and getting over the Great Depression in 1940 | 12. ABC Premium News, 1 July, 2015, Item: P6S120612441315; JLQ, accessed 23/7/15 |

| 13. Fitzgerald, R, Megarrity, L, Symons, D, Made in Queensland, University of Queensland Press, 2009 | 14. The Courier mail 8 June 1937 |

Further reading

| Brisbane City Council, Reflections on the River, A Brisbane City Council Heritage Trail, 2011 | Department of Environment and Heritage Protection, Queensland, Assessing Cultural Heritage Significance, using the Cultural heritage criteria, 2013. Brochure |

| Saunders, Kay. Between the covers: revealing the State Library of Queensland's collections. Woolloomooloo: Focus Publishing Pty. Ltd. 2006 | Watson, A. Building a Masterpiece: The Sydney Opera House, Powerhouse Publishing, 2013 |