State of Emergency

PAST SHOWCASE

State of Emergency

- Home

- State of Emergency

/

30 September 2012 – 19 April 2013

kuril dhagun, Level 1

About the showcase

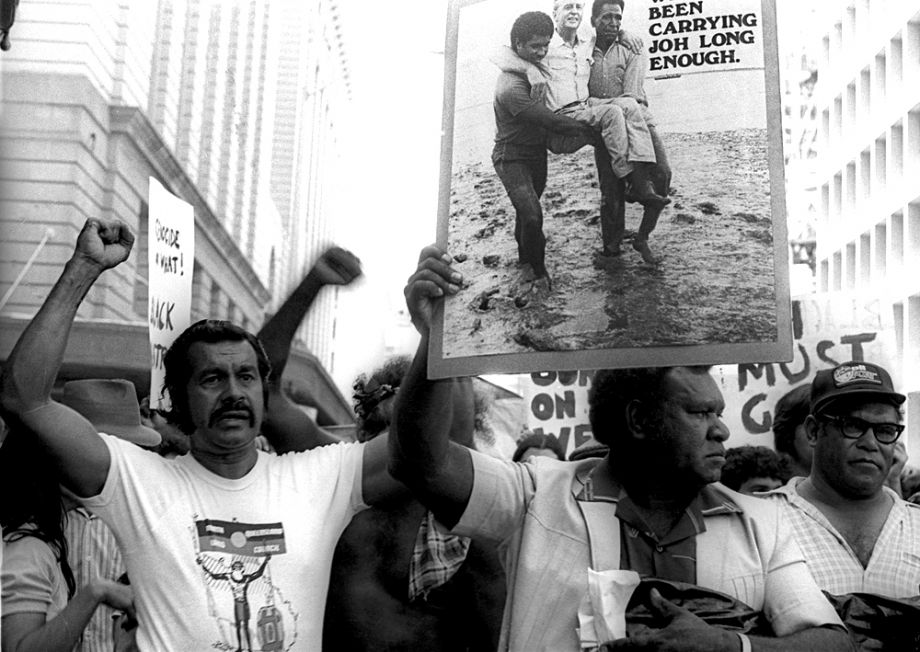

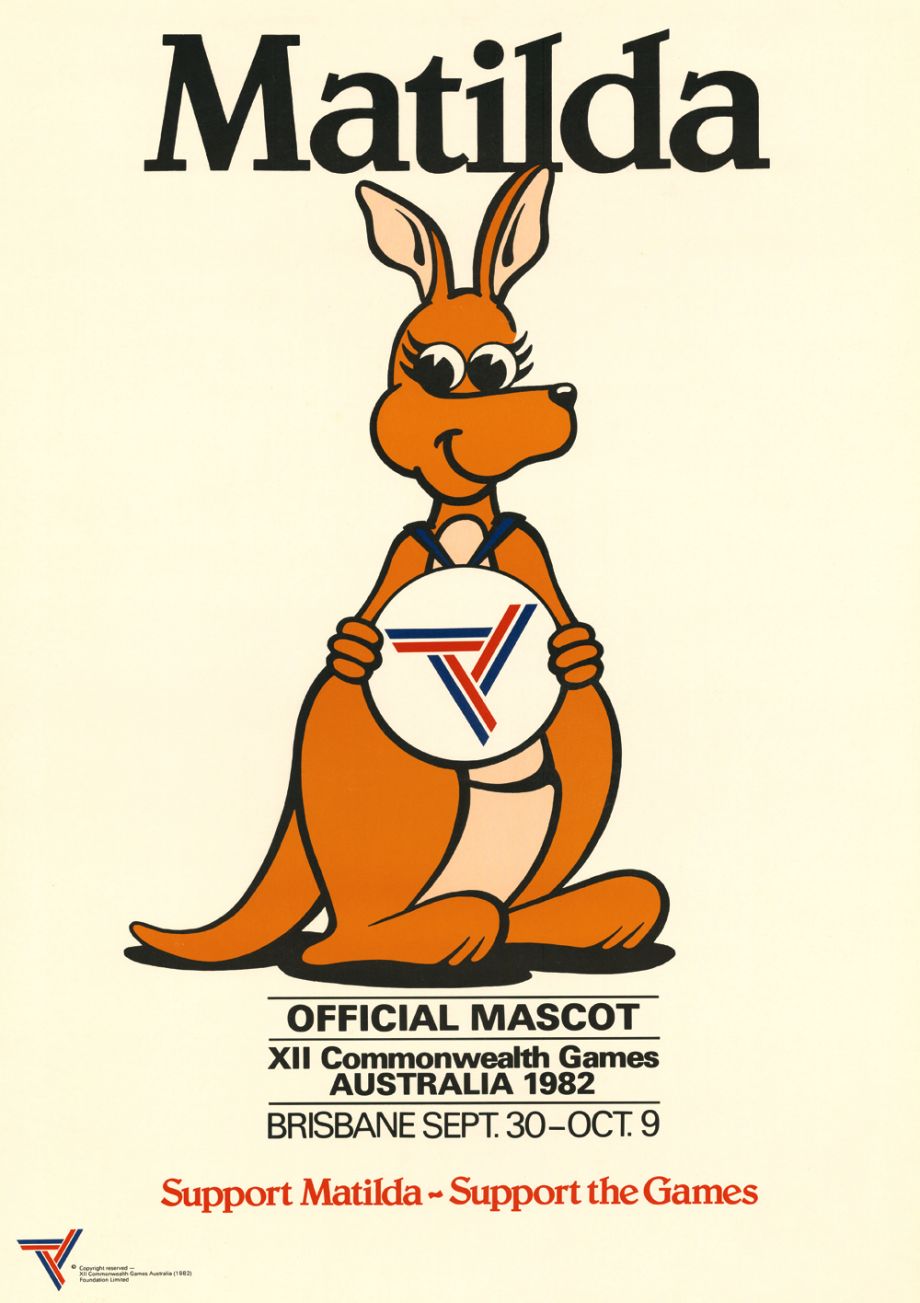

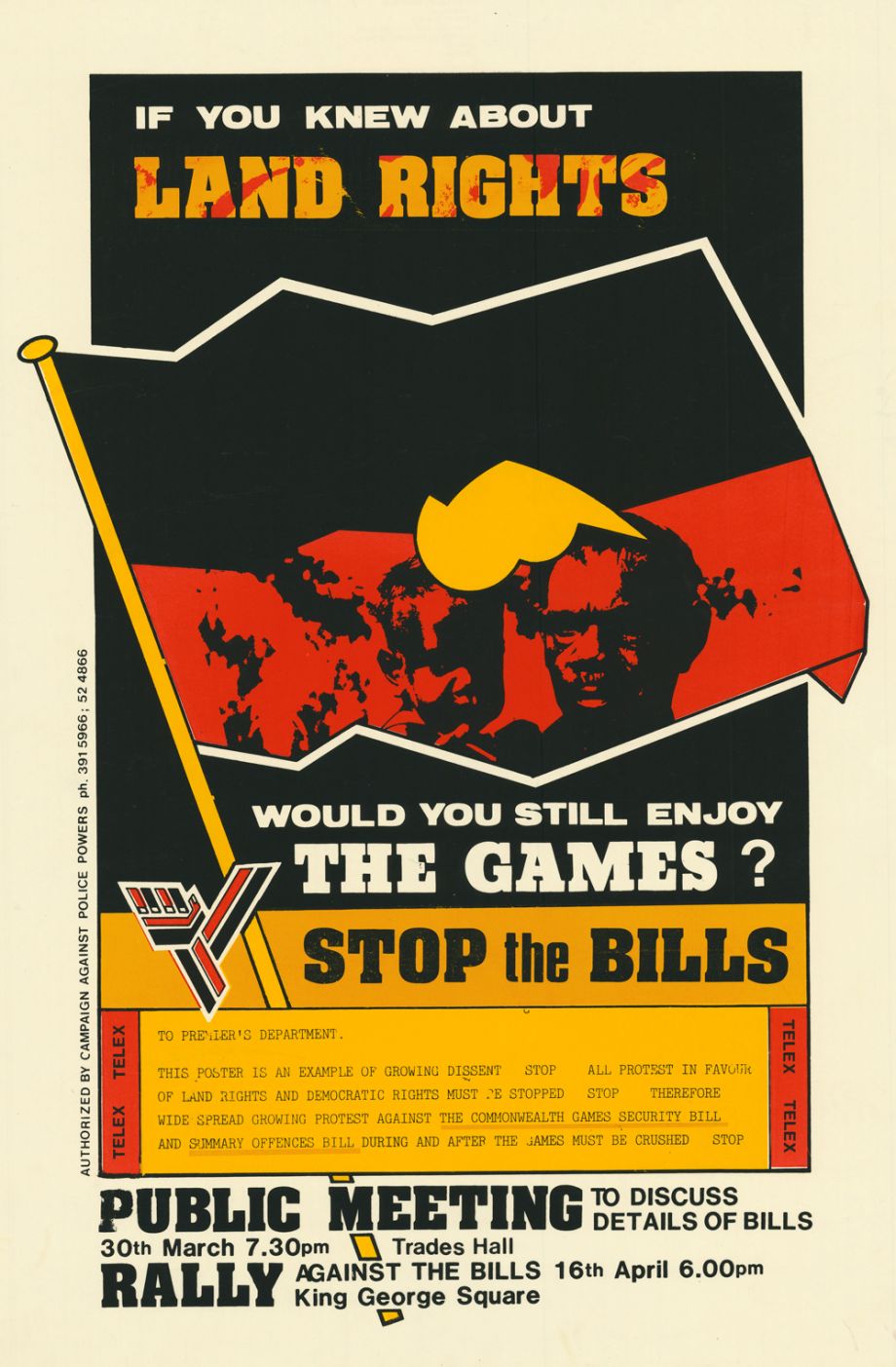

State Library of Queensland marked the 30th anniversary of the 1982 Commonwealth Games when Brisbane came alive with political demonstrations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander civil liberties.

Reflect on the events that took place in Brisbane, the political climate of the time and the history of land rights for Indigenous Australians with this exhibition of original footage, photographs and personal stories from advocators of this revolutionary movement.

Politics and protests surrounding the 1982 Commonwealth Games

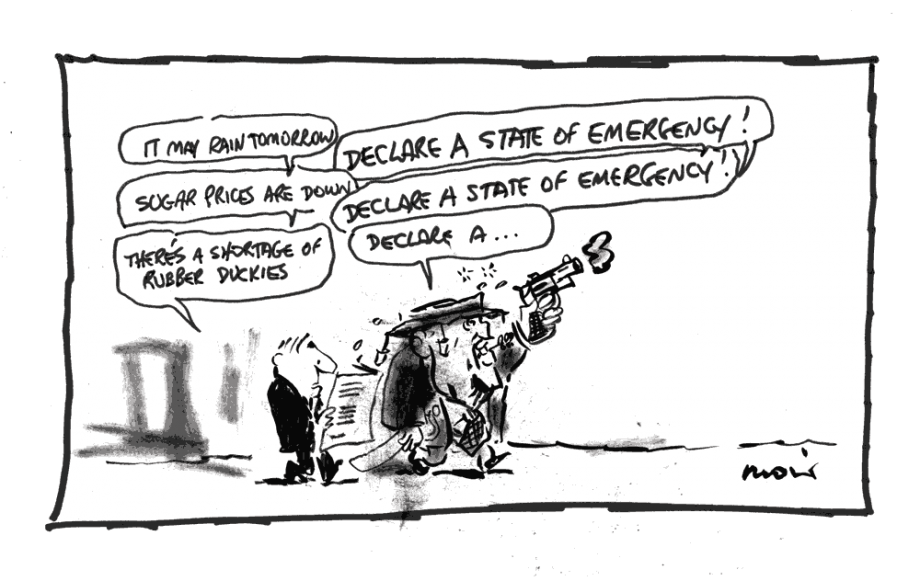

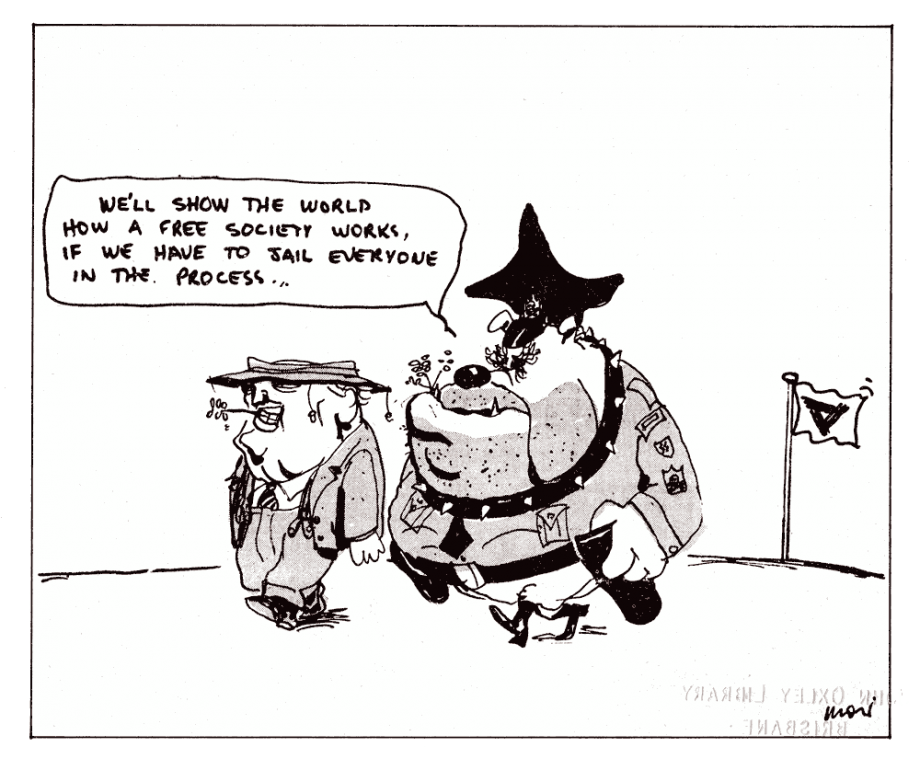

The declaration by then Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen that Brisbane was to host the 1982 Commonwealth Games took place during a long period of struggle for land rights and self-determination by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Queensland. The Indigenous population of Queensland were still living under the conditions of the controversial Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Protection Act 1971 , known as The Act , where they were denied the civil liberties that the rest of the population took for granted.

The Federal Government and the citizens of Australia had voted that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were to be included as citizens of the Commonwealth in The Referendum of 1967, and, in 1971 under the Whitlam Government, there was an amendment to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Protection Act . While still restrictive, this amendment lifted some limitations imposed on Indigenous peoples; however, these Federal modifications did not filter down to State adjustments under Bjelke-Peterson. This resulted in a public struggle between the Federal and State Government in regards to who would be in control of Indigenous affairs. Bjelke-Petersen claimed numerous times that he would repeal The Act, without following through, resulting in the appearance that Queensland was disjoined from the rest of the nation.

The Prime Minister drew criticism to ‘clean up his own backyard’ in relation to Queensland policies because of his strong public stance against South African policies of apartheid. Australia was accused of having double standards as the policies were so similar.

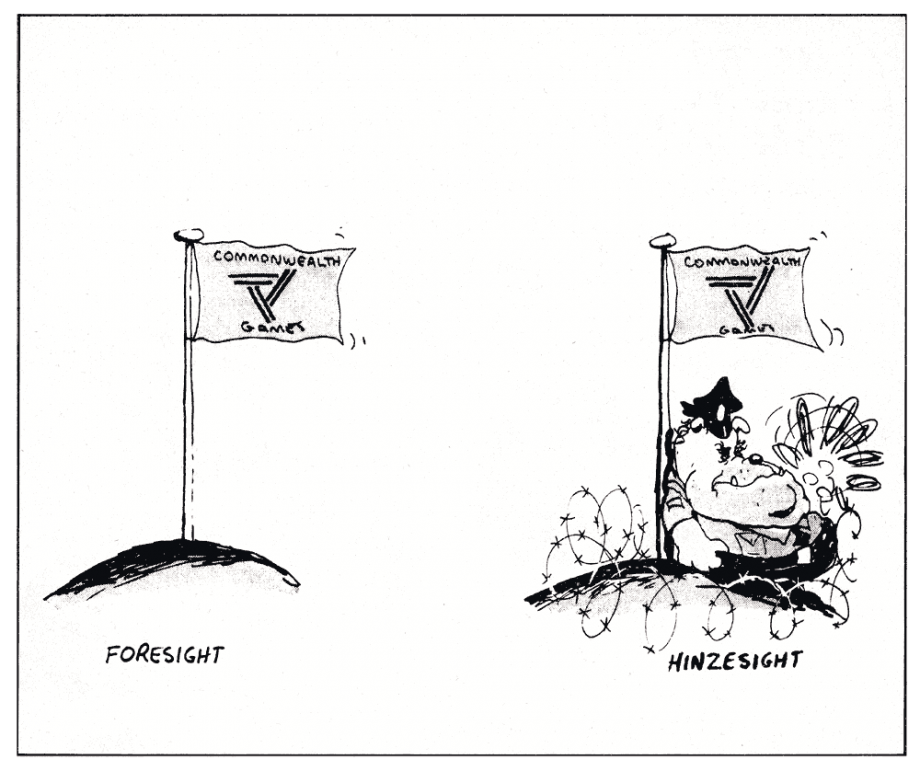

When the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people learned of the announcement that Brisbane was to be the host city to the 1982 Commonwealth Games, it was seen as a platform to highlight their struggle on not only a national, but an international level. Calls for rallies and boycotts were influenced by the Black Power movements of America through the 1960s and ‘70s and their fight for self-determination. While mainstream Australia celebrated the announcement of the upcoming Commonwealth Games, Australia’s Indigenous peoples saw an opportunity to direct international attention to The Act and other issues of concern such as land rights.