- Home

- The 'Shepherd Kings of the Darling Downs': essay

/

The 'Shepherd Kings of the Darling Downs': essay

‘It has been a common custom hitherto to regard the squatters as among the wealthy classes, and they have figured in romance as “shepherd kings” and “grass dukes”, rioting in affluence and far beyond the reach of penury.’

Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, 4 March 1895

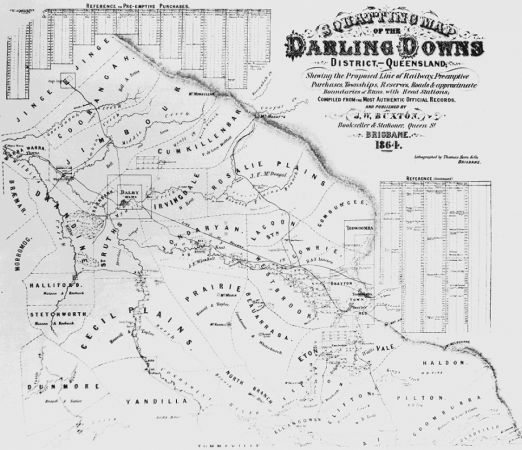

Bounded in the north by the Bunya Mountains, in the east by the Great Dividing Range and in the west by the Condamine River, the Darling Downs area had been home for thousands of years to the Keinjan, Giabal, Jarowair and Barunggam Aboriginal people, who practiced a burning season to manage the grasses of the plains.

The first European to sight the Darling Downs was explorer and botanist Allan Cunningham in 1827, who named the district after Sir Ralph Darling, Governor of New South Wales. He had his first view of the country from the top of the range on 5th June 1827 and recorded these impressions in his diary:

‘On climbing a low stony ridge in our way it was really with the greatest satisfaction that we perceived we had approached within two miles of the Downs, and as small patches or strips of mist extended throughout their whole length, and a line of swamp oak stretched along their south-western extreme, it was clearly shown us that these extensive tracts of timberless lands were not wanting in water.’

Allan Cunningham, Journal, Sept.1822-Feb 1831, quoted in Thomas Hall, The Early history of the Warwick district and the pioneers of the Darling Downs, Toowoomba: Robertson & Provan, 192-?, p.6

Cunningham found fertile, grasslands extending over a wide area of territory; the country was perfect for pasture with a gentle climate, rich soils and nutritious natural vegetation.

Thirteen years after his discovery, the first Europeans made their way to the Downs, attracted by the rewards for producers who could provide good quality raw wool for England’s mills.

Many of these new arrivals were members of a privileged society, younger sons of the English and Scottish gentry, who were obliged to leave home and travel far away in order to make a living. The first to come north were Patrick Leslie and his brother Walter, sons of a Scottish laird, who settled at Canning Downs on the Condamine River.

They were followed by equally well-connected adventurers such as Arthur Hodgson who took up Eton Vale in 1840, the Forbes Brothers of Clifton Station (sons of the Chief Justice of New South Wales) and the Isaac Brothers of Old Gowrie, the sons of a Worcestershire banker. Others included Henry Stuart Russell of Cecil Plains (Hodgson’s cousin) and St George Richard Gore of Yandilla, the scion of an aristocratic Irish family.

This first generation of squatters formed a close-knit community who shared the same values and interests and sealed their associations by intermarrying. Often referred to disparagingly by their critics as ‘Shepherd Kings’ and ‘Grass Dukes’, or in a nod to their obsession with breeding and bloodlines, as ‘Pure Merinos’, they were at the apex of their small society, ruling over a labour-force of itinerant bush-workers, stockmen and shepherds.

The homes which the first squatters constructed were modest slab huts not far removed from the canvas or iron huts of their employees. However, after legal changes in the late 1840s permitted the purchase of pastoral leases, the squatters began to assert themselves and to aspire to a more permanent and impressive presence.

With wool prices rising, they sought political power, lobbying to bring about separation of the northern district from New South Wales. Then in the 1860s, they moved to construct homesteads worthy of antipodean aristocrats and to establish a gracious way of life.

“The normal traveller comes out with introductions to the gentlemen of the colony, and the gentlemen of the colony are squatters. The squatters’ houses are open to him. They introduce the traveller to their clubs. They lend their horses and buggies. Their wives and daughters are pretty and agreeable. They exercise all the duties of hospitality with a free hand. They get up kangaroo hunts and make picnics. It is always pleasant to sympathize with an aristocracy when an aristocracy will open its arms to you.”

Anthony Trollope, Australia and New Zealand, Authorized Australian Edition, 1876, p.24.

The grandest of the Darling Downs houses was Glengallan, a two-storey stone homestead in the plantation style, constructed near Warwick in 1867. Features included a ballroom, specially commissioned furniture and a bathroom with the most modern amenities including running water pumped from the Condamine River.

Westbrook Hall near Drayton was another of the great squatters’ residences renowned for its fine library and marble interiors. A vivid description has been left by Katie Hume, wife of the Land Commissioner for the Darling Downs, who was a guest of owner William Beit in July 1867.

“It was my first visit to this Station. Mrs Armstrong was there to do the honours for her brother, who you know is a widower. We had an excellent early dinner (called lunch) & afterwards inspected the grand new house, which is rapidly rising behind the old one. It is on a grand scale, & will certainly be the finest on the Downs! It is of hewn stone, dark grey (basaltic W. says) quarried on the Run – coins of lightbrick – walls 2ft thick – fireplace in every room-that’s the way to be comfortable in this climate of extremes! It is one storey only – rooms 15ft high – verandah round it 12 ft broad – dining room 30 ft long & other rooms in proportion, including Billiard room, Library etc….Mrs Ramsay is full of envy, their old straggling wooden house is very inadequate for their large family, while Mr Beit will have difficulty in filling his mansion…”

Katie Hume on the Darling Downs: a colonial marriage, edited by Nancy Bonnin, Darling Downs Institute Press, Toowoomba: 1985 p. 70.

The money to build on such a scale came from giant wool cheques (50% of a wool clip was clear profit in the 1870s) and from generous lines of bank credit.

Some of the squatters adopted the manners and habits of the English aristocracy, buying silver, putting down cellars of fine claret and pursuing country house activities such as horse-racing and hunting. At Goomburra station near Warwick, quail were imported to provide sport for guests, and a shooting party of four guns killed 70 brace of quail in 1878. At Headington Hill, south of Toowoomba, owner George Davenport introduced pairs of hares from England, with the idea of providing ‘capital sport’. [Queensland Figaro and Punch, 3 March 1888 p.16] Their descendants became a well known sight around Clifton and Allora.

The way of life established by the ‘Shepherd Kings’ of the Darling Downs lasted less than fifty years. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, they were faced with changing political attitudes, as successive governments introduced land acts designed to reduce their enormous holdings in support of closer agricultural settlement.

Financially, the pastoralists were dependant upon a system which could no longer promise them a rich living. Up until 1866, profits from both wool and cattle were high. Then following a depression, there was another period of prosperity which lasted from 1871 to 1877. After these good times, the pastoral industry began to change irrevocably. Affected by droughts and floods, poor seasons and increased costs, the properties became a burden, funds dried up (especially in the 1890s) and sheep and cattle production became much less profitable.

Some big land holders saw the writing on the wall at an early stage and diversified into farming. Others continued to live on their borrowings or the proceeds of increasing land sales.

By the end of the century, the era of the pastoral man of property was coming to an end. The colourful affluent squatter had ceased to be the face of the Darling Downs.

Further reading

|