These are things I keep banging on about: that libraries continue to evoke a powerful sense of promise; that not much more than twenty years ago the promise of libraries was fairly readily identified with a more or less stable set of practices but since then the relationship between promise and practice has become uncertain.

In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis many municipal governments across Britain and the United States, having adopted austerity policies (either in accord with the constraints or requirements imposed by state or national governments or by their own volition) sought savings in cutting public library funding. Invariably communities responded with a depth of feeling conveying the enormous value of public libraries perhaps more powerfully and incontrovertibly than anything else.

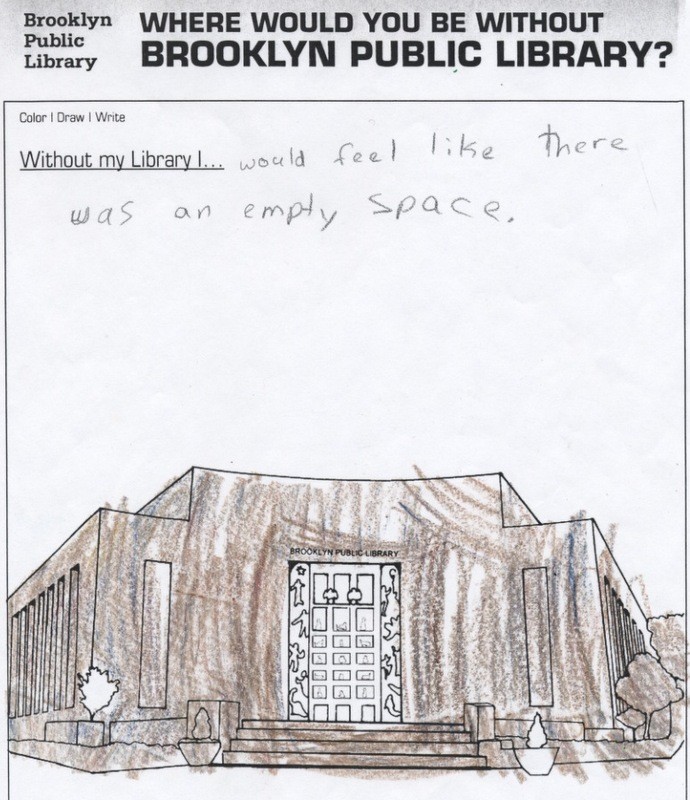

What exactly is taken away when a community loses its library? I’m always struck by the story of children in a part of Brooklyn, New York City, encircling their library, holding hands; one small, poignant response to a massive cut to the Brooklyn Public Library in the 2013-14 New York City budget – nearly $30 million or over 30% of the library’s operating budget.

New York City’s administration had been attempting to impose deep cuts on all three of New York City’s library systems since 2008. Cuts incorporated in annual City budgets were always wound back in the legislative process, but always only partially. Funding to the Brooklyn Public Library had already decreased 19% over five years when the 2013-14 City budget was brought down.

Within weeks of children encircling the Park Slope branch of the Brooklyn Public Library New Yorkers elected a mayor with quite different policies to his predecessor and quite a different take on the value of public libraries. Library funding was restored and, recently, has even been increased. But such a happy ending is exceptional. Elsewhere public libraries have not fared so well. In Britain 1,000 (over 20%) have been forced to close since 2009.

Cuts to public library funding are usually advocated on the basis that the rise of new technologies and the availability of alternative sources of information have diminished the need for public libraries. Any idea that the need for a surviving part of the much reduced structure of public provision is diminishing may appeal to some. More opaquely, ambivalence towards the democratic values foundational to the institution of the public library – mass enlightenment, the democratisation of intellectual freedom and so on – may constitute another ulterior motive for casting doubt on the future of public libraries. But notwithstanding ulterior motives, it does seem that such doubts are harboured ever more widely, even if only unconsciously or with the barest consideration. Thus evidence that public libraries are thriving in many parts of the world is increasingly likely to come as a surprise. Certainly it surprises me.

While looking into cuts to public libraries in the United States I came across a 2013 report by the Pew Research Center, Library Services in the Digital Age. At first I took it to be just another celebration of the virtualisation of library services but it turned out to be the findings of empirical research into whether or not public libraries are maintaining a place in the lives of Americans, in what is undeniably a digital age.

According to the Pew report, 59% of Americans aged 16 and older had visited a public library or had used online public library services within the previous twelve months. Of that cohort 52% said that over the last five years their use had not changed, 26% said their use had increased and only 22% said their use had decreased. 91% of Americans ages 16 and older say public libraries are important to their communities and 76% say libraries are important to them and their families.

Other findings of this research are equally surprising, at least to me:

- 80% of Americans aged 16 years and older say that borrowing books is a “very important” service libraries provide.

- 80% say reference librarians are a “very important” service of libraries

It’s not all that remarkable to believe things in the face of contradictory evidence. What’s more remarkable is believing contradictory things – for instance, deeply valuing your own public library – perhaps even enough to stand around it holding hands if it was ever threatened – but simultaneously believing that public libraries face inevitable decline. It’s a pity that the Pew survey didn’t include the question, “Do you think that public libraries have a future?” If I was asked this question I would reflexively say, “No, because the rise of new technologies and the availability of alternative sources of information is making them redundant”. But however robotically I would say this, I would say it with sorrow, and also a sense of confusion for feeling somehow compelled to say it, without knowing why.

How miserable it is to cherish something while simultaneously feeling resigned to its loss – because of the remorseless march of structural change or because ‘discretionary’ public services like libraries have become luxuries that communities can’t afford, or for some other unfathomable reason.

I showed a draft of this post to a colleague a week or two ago. She said it was OK, if a little gloomy. I delayed doing anything with it while I agonised about her remark. For sure I'm talking about a certain type of gloominess, but that’s not necessarily the same thing as being gloomy.

It’s a wonderful word: gloom. Say it to yourself and you might find yourself laughing with relief. Gloom, of course, is a protective carapace around a vibrant promise. But the thing about a promise is that it’s its own affirmation. It shines on in the face of hostile circumstances, even in spite of gloom.

No doubt the cruel ritual of being dangled over an abyss every year for the past five years caused gloom within the Brooklyn Public Library. But that’s not what you see when you look at its website, or back through its Facebook page or peruse the public record of its trials and tribulations. Something else shines through – something vital, irrepressible, incontrovertible - definitely reason to be cheerful.

Do libraries continue to be necessary to fulfilment of the promise of libraries? Much flows from the answer to this demanding question; demanding because before you can legitimately answer it you have to really deeply grasp what the promise is; you have to grasp what actually happens in public libraries - myriad small miracles every day. I’ll explore these matters further in my next few posts. Watch out for them; every two weeks, for a while.

This video, part of a campaign to extend the opening hours of New York public libraries has some wonderful moments.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.