My last post juxtaposed the passionate way communities in Britain and the United States have invariably responded to the wave of cuts to public library funding that have swept those countries in recent years with what I take to be the pervasiveness of the view usually invoked to justify such cuts – that the institution of the public library is in decline. How troubling it is when the narratives by which the world is understood foretell the loss of something cherished.

Public library use may be increasing in the United States but in many parts of the world it has certainly been decreasing for some time. But even where use of public libraries is in decline, communities still rise passionately in their defence when they’re threatened. How is it that something can be used less but valued no less strongly?

Our own research has repeatedly shown that positive feelings about libraries correlate only weakly with levels of use. It also shows that the marked tendency for people to feel in some way special when they’re visiting a library varies surprisingly little with what people actually do while visiting. Even activities that in any other context would be generally considered fairly unremarkable – homework, checking emails, fiddling with a mobile device, gazing into space etc., take on something of a hallowed quality when undertaken in a library. Libraries, it seems, have this enormously powerful symbolic resonance with roots extending beyond the here and now, even beyond personal experience. On entering a library; even on simply thinking about libraries, a promise starts to resonate.

A promise is an assurance that something will or won’t happen; it engenders a sense of expectation. Conversely, a promise may be taken as implied by a sense of expectation, even without being literally or obviously declared. The sort of expectation engendered by spring for instance, or libraries, may be taken as implying a promise.

A promise may be fairly universally recognised without being clearly understood. For example, it’s hard to say what the promise of spring, or libraries, is exactly – the expectations that spring or libraries respectively engender or what it is about spring or libraries which respectively engender them. In fact ‘promise’ tends to be used to signify expectation and its causes when we don’t really know what we’re talking about, while being dead certain about what we mean.

A promise can endure, sometimes for a long time, without fulfilment. Hence public libraries continue to be highly valued, even amongst the cohort that rarely or never visits a public library, steadily growing in some places. Sometimes the divergence between a promise and its fulfilment may become too great, or go on for too long, and the promise dims in people’s minds. But it’s quite possible, common even, for a promise and its agent to be in elliptical orbit around each other, sometimes rushing towards each other, before racing away on what, to the ignorant or faithless eye, seem to be sundering trajectories.

That the promise of libraries floats remarkably freely from what libraries actually do confounds the orthodox identification of value with utility. Not obviously rooted in any particular use or combination of uses, the promise may come to be distrusted as a form of irrational sentimentality, dismissed as inward or backward looking in favour of something else made of sterner stuff, more in keeping with sober utilitarian discourse – that libraries are good for educational outcomes, for instance, or social cohesion or even economic growth.

That libraries demonstrably have all sorts of positive outcomes is great, but misses the point – why they’re actually valued. In fact it seems more likely that libraries have all sorts of wonderful outcomes because they are so deeply valued – not the other way round. Do libraries do good because they’re loved or are they loved because they do good? These are important questions with enormous implications for what libraries do and also what policy makers expect of them or require them to do.

The issue here isn’t whether value should or shouldn’t be reducible to utility. If value lies in the eye of the beholder then surely the obvious place to start in understanding what makes something valuable is the sense of value it evokes – its promise. No doubt at the root of the promise of libraries is something libraries actually do, or used to do or even might do, however understanding exactly what that is depends on starting from the right end – with the promise, rather than with preconceptions about what constitutes value. Being merely useful doesn’t necessarily make something valuable. To be valuable libraries needs to be what they’re valued for. But what is that exactly? What exactly is it about libraries that summons such an extraordinary sense of promise?

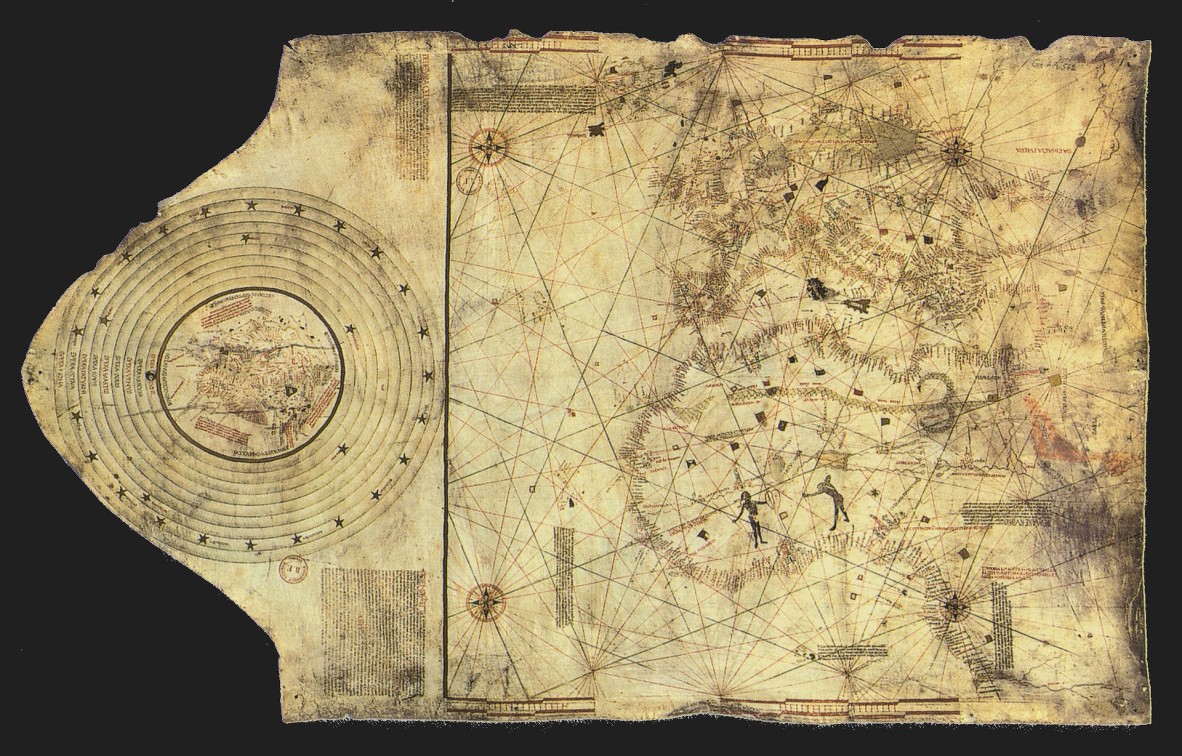

The most epic journeys may start with the simplest of questions and sometimes end up answering some other, possibly more interesting, question. Take Christopher Columbus, who thought it might be quicker to get to the Orient by sailing west rather than east. This was generally considered a crazy idea and he struggled to gain the funding required to discover America.

Christopher Columbus wasn’t considered crazy because, as popular myth would have it, he believed the world was round when everybody else laboured under the delusion that it was flat; for by that time the shape of the world was generally understood. He was considered crazy because (a) reliable land routes to the East had been established for some time and (b) the prevailing consensus, correct as it turned out, was that the world was much bigger than he optimistically thought.

I often think of Christopher Columbus, clutching his map, doggedly going from one financier to another, at each audience getting a little too excited perhaps, tripping over his words…

By Columbus’s time the shape of the world was generally understood, but perhaps what distinguishes him is a preparedness to believe his own dangerously optimistic map. When he reached the West Indies he confidently assumed he’d reached India. The Americas stood in the way of his voyage to the Orient. Their discovery was a mistake.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.