Bootmakers of Brisbane [Part 1]

By Dr Robin Trotter - 2024 Queensland Business Leaders Hall of Fame Fellow | 8 November 2024

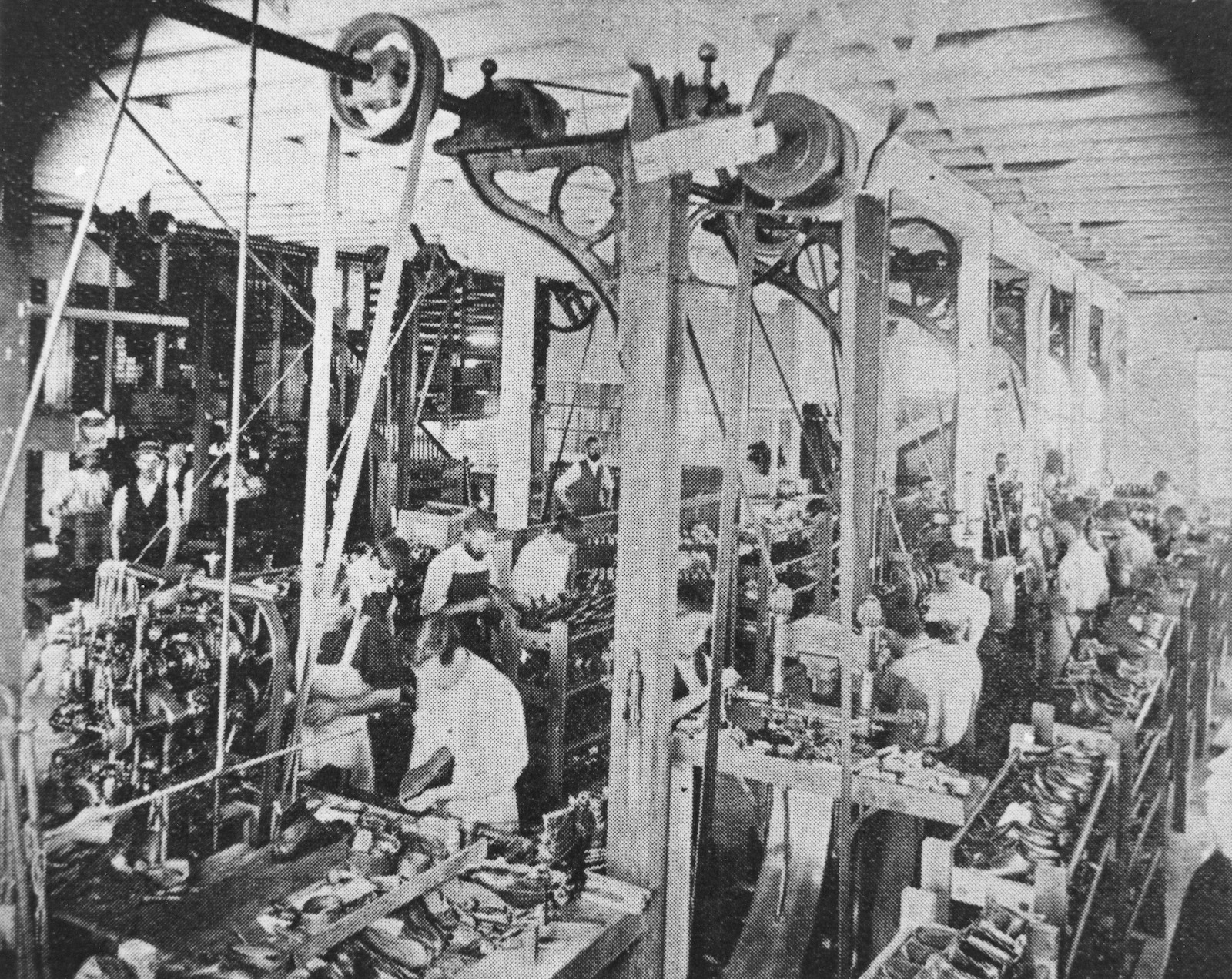

Interior of Astill & Freeman boot factory South Brisbane, 1900, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number:108318.

INTRODUCTION

Dr Robin Trotter, 2021 and 2024 Queensland Business Leaders Hall of Fame Fellow

By the 1890s Brisbane was the recognised centre of industrial development for the new colony. From the date of free settlement the bootmaking trade had grown – an inevitable development given the growth of pastoralism and a burgeoning meat industry (for local consumption and for export), and as a corollary of that, the mushrooming of the ‘skin trades’ (wool scours, fellmongeries and tanneries – see my other blog: The Tanneries of Brisbane Part 1 and Part 2). The leather produced from these operations gave the impetus to a range of other industries and products:

Saddlery | Whips | Harness leather | Travelling trunks | Braces | Straps and strapping | Suitcases | Satchels and bags | Hatboxes | Purses and wallets | Bookbinding | Furniture | Clothing and accessories | Footwear - boots, shoes

I skip over all these products except the footwear industry – or more specifically the bootmaking trade. The story of the bootmaking trade in early Brisbane is the focus of Part 1. In Part 2 the focus turns to Thomas C Dixon & Sons. Thomas Coar Dixon started out making boots in the 1870s and the company only closed its factory doors in 1980. Volume of output, and the quality of the output with the company’s mission to make ‘shoes of distinction’, ensured that the Dixon family bootmaking operation was a leader in the industry for over 100 years.

Well before Dixon started up his bootmaking venture, or his other interest, a tannery operation (see my other blog: The Tanneries of Brisbane – Part 2) there was a burgeoning boot trade in the Moreton Bay area with one of the earliest bootmakers being Thomas Gray. Gray arrived in Brisbane in 1844 (just two years after Moreton Bay was opened up for free settlement) and started up his trade. Initially, it appears. he started as a bootmaker: [1]

In a few short years, Gray added importing and retailing to his business, as we will see later.

Moreton Bay Courier, Saturday 27 June 1846, p 3. Image courtesy of Trove, National Library of Australia.

Portrait of John Hardgrave early resident and mayor of Brisbane 1868-1869, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 63589

John Hardgrave, another early bootmaker of Brisbane, arrived in 1848 (six years after free settlement), and set up a bootmaking operation in the Bald Hills area. His business continued until 1862. Besides his bootmaking interests, The Aldine History of Queensland records that he was mayor of Brisbane (1868-1870), first chairman of the Woolloongabba Divisional Board, alderman for South Brisbane (1888-1890), chairman of the Waterworks Board (1893), one of the founders of the Brisbane School of Arts, as well as being involved with the Hospital Committee and the East Moreton Association (National Agricultural and Industrial Association of Queensland). The Aldine History sums up Hardgrave’s activities:

It is almost impossible to mention an organisation of note in which Mr. Hargreaves [sic] does not occupy an honorable position, and it may be truly said that he is a citizen of the right sort, studying the advancement of his fellows and that of the colony generally. [2]

By the date of separation there was a body of bootmakers in the new colony. The new Governor, Sir George Bowen and Lady Diamantina Bowen, arrived in Brisbane on 11th December, 1859. The next day, Monday, 12 December, a public welcome was held in the Botanic Gardens and officials and dignitaries of Brisbane presented their addresses of welcome. Among these was a deputation of bootmakers (cordwainers) and it was Mr Thomas Gray, our pioneer bootmaker, who presented the welcome:

To His Excellency Sir George Ferguson Bowen, Knight of the Greek Order of St. Michael and St. George, Governor of Queensland, &c,

May it please your Excellency,—

We, the Cordwainers of Brisbane, in the Colony of Queensland, approach your Excellency with feelings of veneration and respect, not only as the Representative of our Sovereign Lady the Queen, for whom we retain the most devoted loyalty and attachment, but as the first Ruler of this our newborn colony.

We congratulate your Excellency upon your safe arrival and that of your Excellency's Lady, and respectfully assure you that your Excellency's person and family will have an abiding place in our affections, and that we shall never cease to uphold as loyal subjects the cause of good government and order.

We have as citizens the highest appreciation of the political privileges so graciously bestowed upon us, and hail your arrival as the advent of a new era in the history of this portion of Her Majesty's dominions, and anticipate that your rule will be productive of salutary results.[3]

Portrait of John Hardgrave early resident and mayor of Brisbane 1868-1869, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 63589.

Whilst bootmakers and boot factories were not limited to the south east corner of the colony, this story focuses on the Brisbane scene, and it is interesting to read a contemporary report on the local bootmaking trade. Barton, editor of the Jubilee History of Queensland (1909) records that initially there was a reluctance of the population to accept locally produced footwear but over a short period this had been overcome by bootmakers moving to ‘models and methods’ that met the requirements of the local market. There were other problems for local bootmakers: intercolonial trade barriers (largely addressed with Federation in 1901); differences of opinions and expectations in terms of wages and working conditions (somewhat addressed by legislation on working conditions and wage regulations after the Bootmakers Strike of 1890); and the impact of industrialisation and mechanisation of the trade which also created both advantages and disadvantages, one being Queensland’s smaller population as compared to the southern manufacturers with larger markets which made mass production and product diversity more financially viable in the more populated colonies. [4]

Before looking at some Brisbane bootmakers and their operations, I will explore some of the above events and issues around the Brisbane footwear trade.

Prior to the mid 1800s – and mechanisation of the bootmaking process that then facilitated the factory system, bootmakers (or cordwainers) generally worked individually (or with an apprentice) under a guild system – as illustrated below:

The Shoemaker, c.1650, David Teniers, Photo by Northampton Museum & Art Gallery.

Cobbler and apprentice, photo courtesy of St Ives 100 Years Ago.

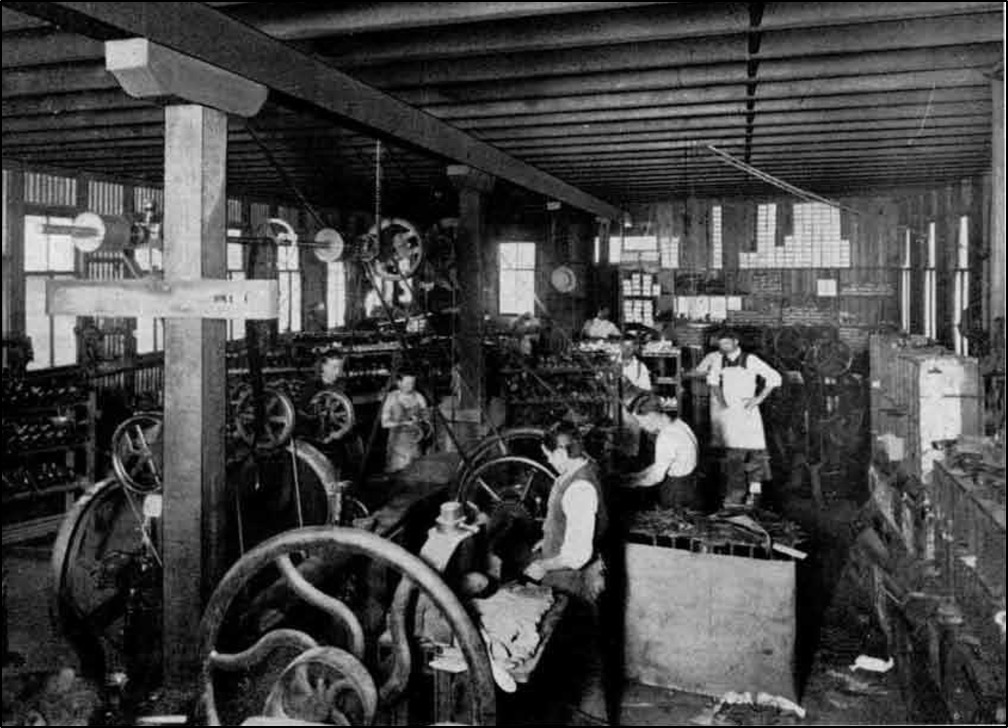

Early steps in the mechanisation of shoe and boot production was the invention of the sewing machine in 1829 by French tailor, Bartheley Thimonnier, which led to the later invention of a boot stitching machine by American inventor, Lyman Reed Blake (patented 1853). The Blake Sewer stitched the sole of a shoe to the upper [5] and this is a similar machine made by Bradbury & Co, UK, and used by a Sydney bootmaker:

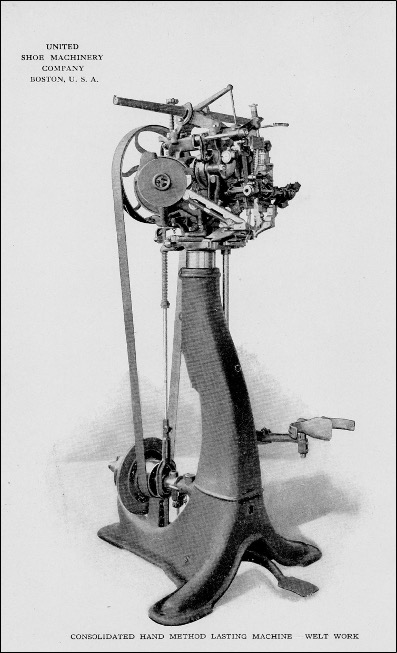

Another major invention that helped pushed traditional methods of boot and shoe making into factories and mechanised operations was Jan Ernst Matzeliger’s shoe-lasting machine (patented 1883). [6] This mechanically shaped the upper portions of shoes and speeded up the process of constructing a shoe:

Boot-stitching machine, treadle operated, cast iron / wood, made by Bradbury & Co Ltd, Wellington Work, Oldham, Greater Manchester, England, 1878-1890, used by the Hamey family of boot-makers in New South Wales, Australia, c. 1880-1979. Photo courtesy of Powerhouse Museum, Sydney.

The Matzeliger Lasting Machine, 2019. Photo courtesy of CTW Photography.

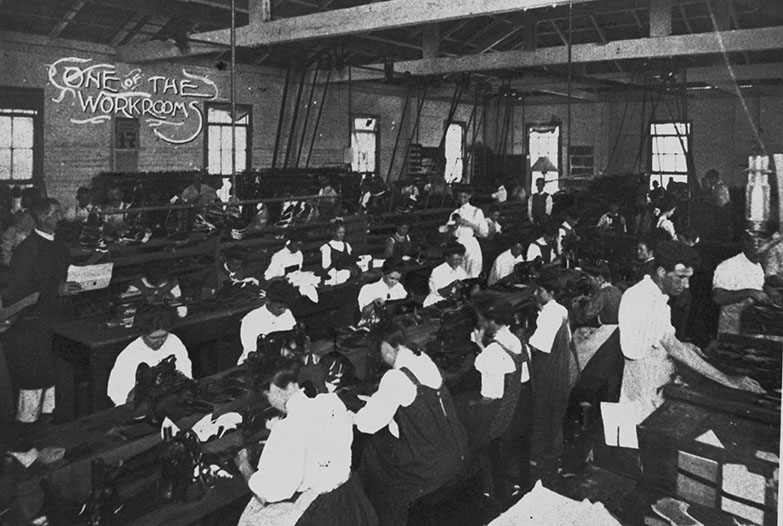

These technological developments, alongside others, pushed what had previously been a cottage craft into factories or workshops and into an industrialised operation. It also enabled women to be employed to undertake mechanised tasks previously undertaken by male craftsmen and thus brought about feminisation of some processes in the manufacture of boots. Bradley and Toni Bowden (2004) in their study of the Brisbane boot trade note that ‘those engaged in the 'manufacture of fabrics', including footwear, were already the city's largest single occupational sub-category (other than domestics)’ and as mechanisation of the boot making process was introduced, women were increasingly being employed as machinists to stitch the boot uppers, leaving male workers to handle the heavier tasks. So, unsurprisingly, when the Secretary of the Amalgamated Operative Boot Trade Union - William Strickland – gave evidence to the 1891 Royal Commission into Shops, Factories and Workshops, he commented that it was 'the women [who] do the machinery' [7].

Employment of women – and also children – was being spurred on by a series of strikes in the boot trade. The Amalgamated Operative Boot Trade Union (AOBTU) had been formed in 1887. It was one of Brisbane’s largest unions and also extremely militant. Its members were agitating around issues of wages, child labour, working conditions and sweating. There was simmering activity from the AOBTU from around 1890 which erupted into strike action on 23 May 1890. The strike lasted till 11 June and according to historians R J and R A Sullivan, ‘The settlement produced substantial gains for the bootmakers, including the abolition of outside work, a limit on the number of apprentices, and an increase in rates of pay’.[8] This did not conclude disputes between bootmakers and employers, as was evidenced in evidence from witnesses at the 1891 Royal Commission, as well as the long running bootmakers’ strike of 1895 which lasted 11 weeks and saw the strikers defeated and having to accept reduced wages and increased mechanisation.

A key figure in these conflicts in the boot trade was Frank Harris (1878-1961). He was President of the Boot Trade Union of Brisbane during the 1905 strike, Secretary of the Queensland branch of the Australian Boot Trade Employees Federation (1907-1942), the Queensland representative on the Federal Council of the Australian Boot Trade Employees Federation and later President of the Federation (1922).[9]

The Australian Boot Trade Employees' Federation Federal Council. Photo courtesy of Open Research Repository, Australian National University.

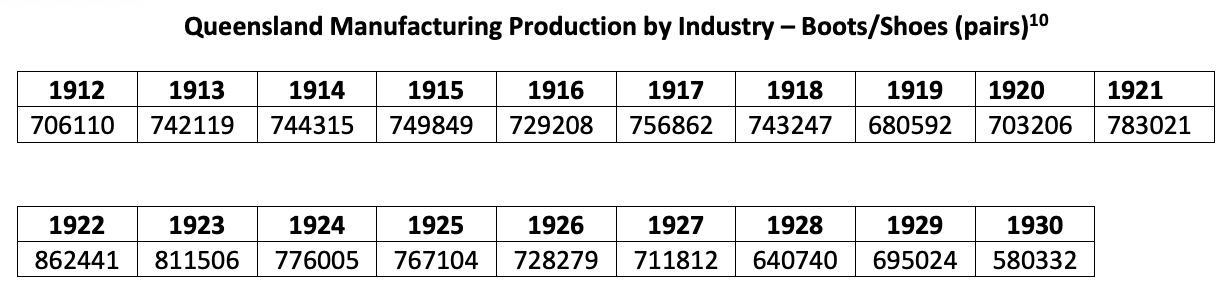

The ongoing agitation and conflicts are evidence of the value and importance of the boot/shoe trade, the growth of the industry and the economic contribution this sector has made to the Queensland economy as these figures for the production of boots and shoes in Queensland from 1900 to 1930 from David Cameron’s study of the economic development, manufacturing and political economy of Queensland from 1900 to 1930 attest:

Queensland Manufacturing Production by Industry - Boots/Shoes (pairs)[10]. Table courtesy of the University of Queensland.

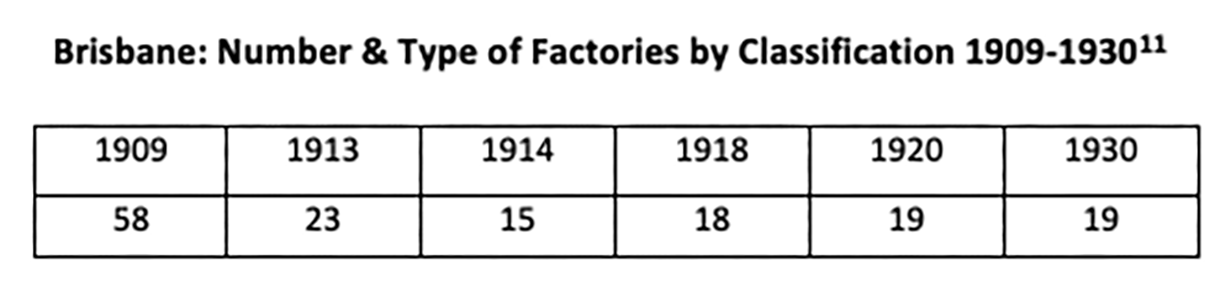

How these data translate into the Brisbane scenario is the subject of further research, but Cameron does give an indication of Brisbane factories involved in boot/shoe manufacturing:

Brisbane: Number & Type of Factories by Classification 1909-1930 [11], Table courtesy of the University of Queensland.

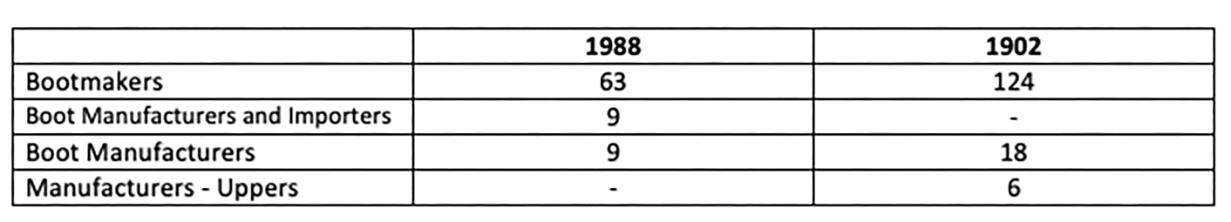

Various commentators – contemporary and recent – give mixed accounts of how many bootmakers there were in Brisbane at various times. Pugh’s Almanac from 1888 and 1902 shows an increase not only in numbers of bootmakers but also a degree of specialisation developing:

Pugh’s Almanac from 1888 and 1902, Table courtesy of Pugh’s Almanac from 1888 and 1902.

THE BOOTMAKERS

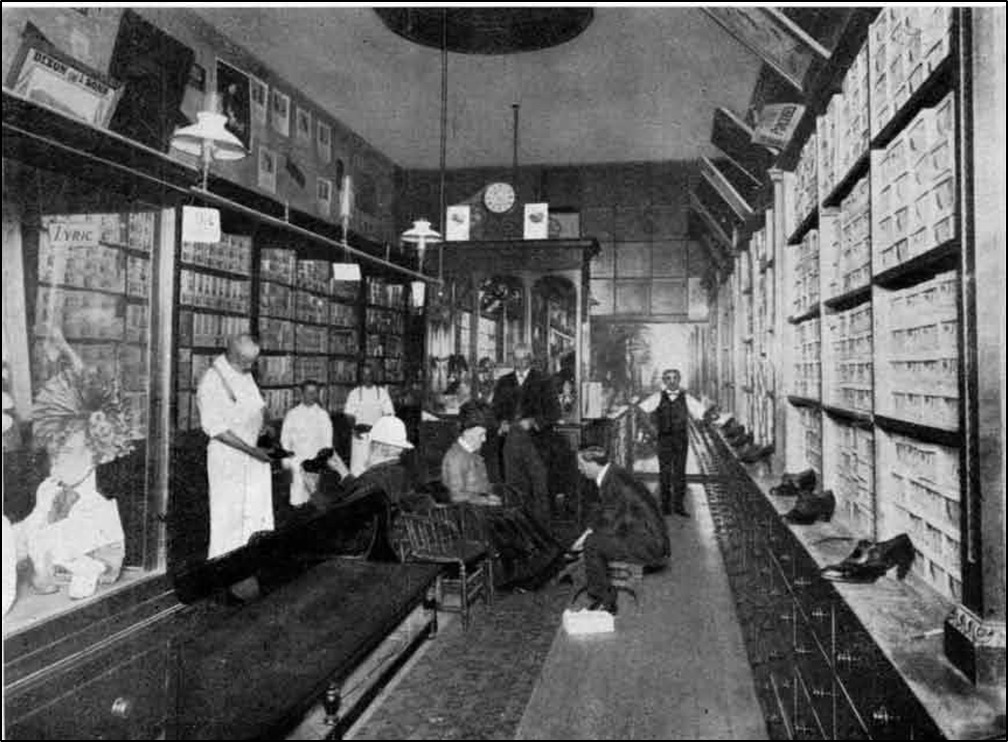

Let’s look at a selection of these bootmakers and the factories that produced the increasing volume and value of locally produced footwear, but first this image, c,1900, which depicts a typical retail outlet for both locally manufactured and imported footwear. This is the George Street, Brisbane, retail establishment of our pioneer bootmaker, Thomas Gray - T & W Gray:

T. & W. Gray, Boot and Shoe Importers, George Street, Photo courtesy of Jubilee History of Queensland, p.247.

ASTILL & FREEMAN, SOUTH BRISBANE

Joseph Astill and James Henry Freeman started their bootmaking business in, first Tank Street, Brisbane, and then Mary Street, Brisbane, before building a substantial factory in Cordelia Street, South Brisbane, in 1887. After the deaths of both Astill and Freeman, the business continued under various owners whilst maintaining the names of Astill and Freeman up until 1964 when the operation was sold to Jolly & Batchelor Pty Limited, manufcturers of a range of leather goods. That business closed in 1994. The buiding remains and today is heritage listed as an ‘example of a former nineteenth century boot-making factory’.[12]

Astill & Freeman's leather factory South, Brisbane, 1900, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 108317.

F T MORRIS BOOT FACTORY

David Loosemore, great great grandson of the founder of the Morris Boot Factory, records:

The Factory was started up by my great-great-grandfather Reuben Morris and his sons Frederick and Henry in 1888, named ‘R. Morris and Sons’ … [at one point] the company employed up to 180 workers and could make 630 pairs of boots and shoes a day. They sold direct to retailers from Mount Isa to Melbourne … In 1940, the factory was making ‘cossacks’, scout boots, cane-cutters’ boots, ‘railway boots’, and dress boots. Riding boots were popular, and in the late 1950s they made safety boots for construction workers with steel protection in the boot. They also made sandals, dancing shoes that were popular in the jazz era, and children’s shoes.[13]

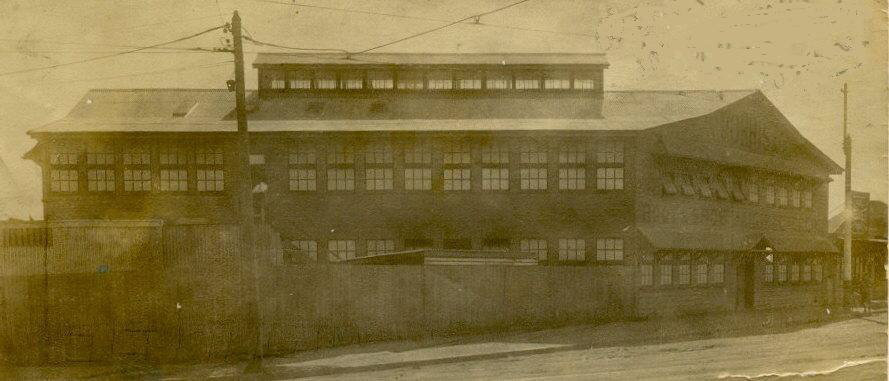

F T Morris’s Boot Factory, Latrobe Street, Paddington, c,1925. Photo courtesy of David Loosemore's family stories

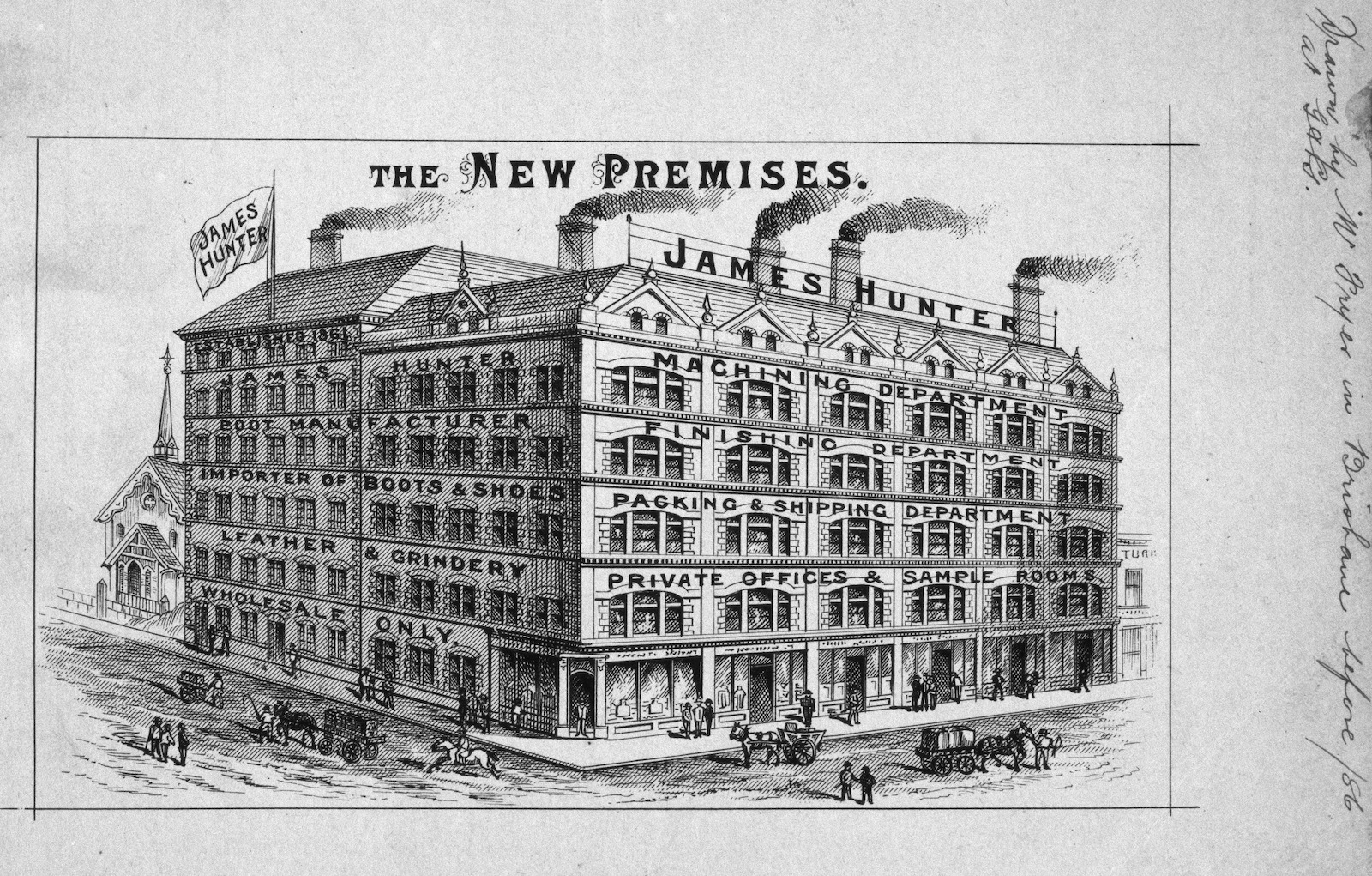

HUNTER’S BOOT FACTORY, Elizabeth Street, Brisbane.

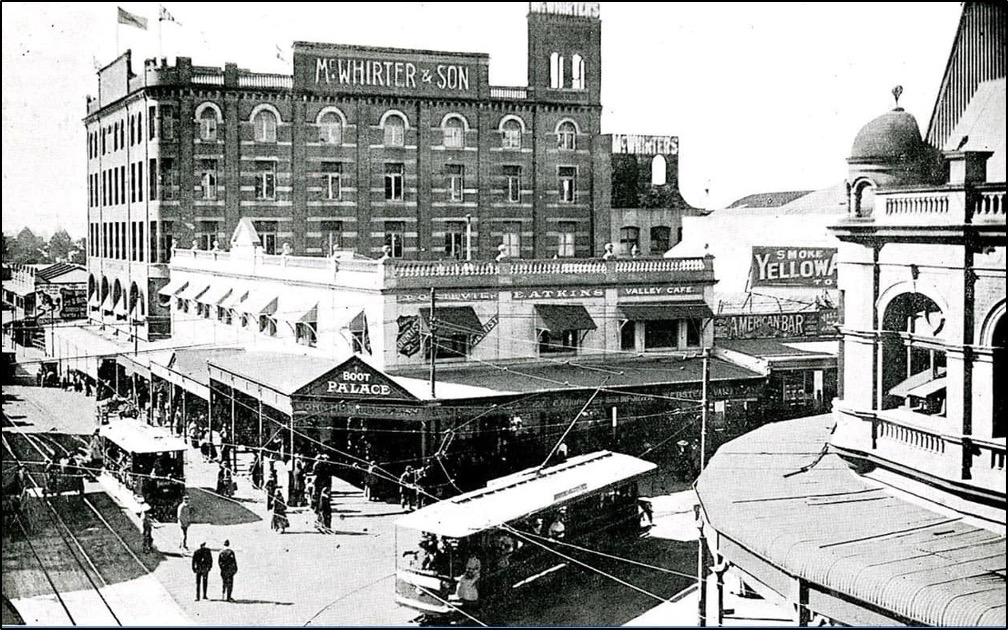

Established in 1861, John Hunter’s boot factory was described in the Brisbane Courier, 13 June, 1884, as ‘the largest factory of the kind in the colony’.[14] Hunter was both an importer and manufacturer who, under the name John Hunter & Sons, established a bootmaking empire with a network of factories and shoe retailing outlets around the nation, such as the Queen Street, Brisbane shop and factory (below), and the Hunter Shoe Palace in Fortitude Valley (below):

Drawing of the James Hunter boot factory Brisbane, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 190779.

James Hunter’s Boot Palace, Fortitude Valley, Passing Time. Photo courtesy of Passing Time.

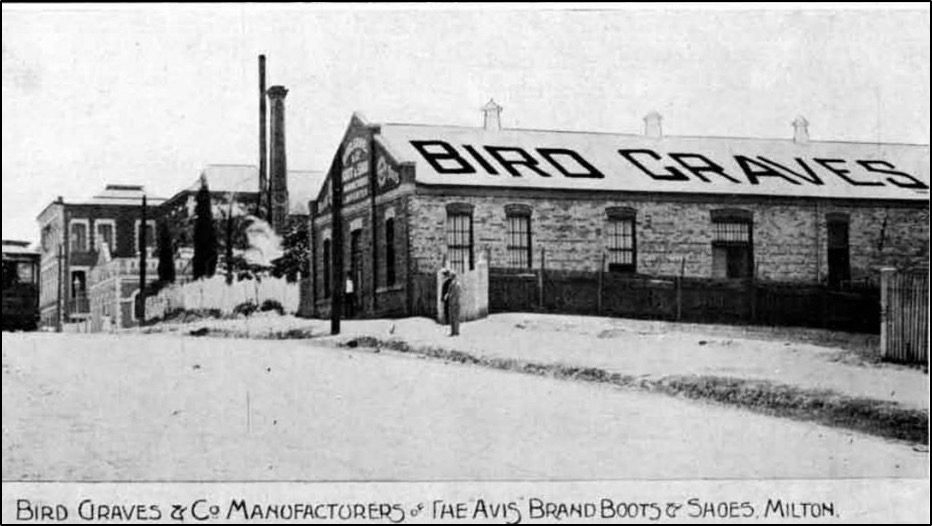

BIRD, GRAVES & CO., MILTON

Starting as a boot importer in 1891, E D Bird was subsequently joined by J B Graves in his importing business which Bird had established in Edward Street, Brisbane. In 1897 the partners expanded into boot manufacturing with a factory established alongside their importing warehouse. The business prospered and in 1903 Bird and Graves moved to a new building in Milton (close to the Milton Station and Castlemaine Brewery). The company specialised in the production of women’s shoes, and made famous their Avis brand shoes. [15]

Bird, Graves & Co, Manufacturers, Edited by Barton, E. J. T. Brisbane. Diddams, p.248, 1910, Jubilee History of Queensland. Photo courtesy of Text Queensland.

Interior of Bird Grave & Co. shoe factory at Milton Brisbane 1909, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 10383.

THOS. BAYTON, WOOLOONGABBA

Thos. Bayton Boot and Shoe Manufacturer, according to the Jubilee History of Queensland, specialised in ‘ladies’ and children’s light shoes’. The business had been started by Thomas Bayton in 1899 in a small shop on Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley, with no machinery and three workers. After Bayton’s death in 1909, his widow and son carried on the business and moved to a larger operation in Balaclava Street, Woolloongabba. The new factory was fitted out with up to date machinery and employed twenty workers.[16]

Thos. Bayton, Boot and Shoe Manufacturer, Balaclava Street, Woolloongabba., Edited by Barton, E. J. T. Brisbane. Diddams, 1910, Jubilee History of Queensland, p.321, Photo courtesy of Text Queensland.

QUEENSLAND CO-OPERATIVE BOOT SOCIETY LTD., WOOLLOONGABBA

Established 1912 with a directorship made up predominantly of men from the boot trade: Percy Brampton (Mercantile clerk), John Wilson (Boot pressman), George Bennett (Bootmaker), Albert William Stenner (Boot finisher), Heinrich Kluver (Boot finisher), William Strickland (Factory manager), and John Kersley (Solicitor). Strickland, as mentioned earlier, had given evidence at the 1891 Royal Commission into Shops, Factories and Workplaces whilst he was Secretary of the Amalgamated Operative Boot Trade Union. [17] ‘Passing Time’ researcher suggests this business started earlier – possibly as a consequence of the 1895 Bootmakers’ Strike which saw workers involved with the strike, losing their jobs:

The earliest reference to the Queensland Co-operative Boot Society appears in August 1904, which suggests that the business was operational by this stage. By October 1908 advertisements began appearing indicating that the Queensland Co-operative Boot Society was controlled by the Operative Boot Trade Union. This advertisement also suggests that the business was established in 1895, which is the same year of the workers strike...This workers strike spanned 14 weeks between May 1895 and August 1895, which included all of the boot manufacturers in Brisbane. It was ended due to starvation and resulted in workers returning to their jobs at one of the companies at a 35% pay decrease. Most of these workers then lost their jobs in 1897 when machinery was automated. It appears that by the time of this 1908 advertisement the boots were being manufactured in a factory in Milton, which were then being sold at a retail outlet located at 113 Queen Street in Brisbane.[18]

Factory workers outside Queensland Co-operative Boot Society Ltd., Woolloongabba, 1919, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative number: 65786

CONCLUSION

The above boot and footwear factories are only a selection of the boot trade in early Brisbane – as indicated by the figures cited earlier. The strength of the boot trade in the late nineteen and early twentieth century contributed to Queensland’s economy, employed and upskilled a body of trades people, and helped to build Queensland’s domestic industrial infrastructure. And yes, there were pressures and social issues around wages and working conditions that are part of our industrial history. As competition from overseas, and from new products, and national trade policies impacted on the boot trade, many of these businesses disappeared. One that did continue to 1980 was T C Dixon & Sons, West End, and the story of that boot factory is the topic of ‘The Bootmakers of Brisbane - Part 2: T C Dixon & Sons’ (forthcoming).

Other blogs by Dr Robin Trotter, 2021 and 2024 Queensland Business Leaders Hall of Fame Fellow

- Bootmakers of Brisbane [Part 2]

- The Pioneering Hide, Skin and Leather Industries of Brisbane: The Dixon Tanneries [Part 1]

- The Pioneering Hide, Skin and Leather Industries of Brisbane: The Dixon Tanneries [Part 2]

- Frank McDonnell And The Early Closing Movement

- How to make a Carton: history of paper making in Australia

- The making of a Knight: Sir Arthur Petfield

- A Career in Cards

- How Napoleon's pistols came to Queensland

- Sir Arthur Petfield and 'The World Shrinkers'

REFERENCES

[1] Morrison, W Frederick, 1888, The Aldine history of Queensland, in two volumes. The Aldine Publishing Co. Sydney, Appendix

[2] Morrison, ibid., p.441-2.

[3] ‘Arrival and Reception of his Excellency, Sir G F Bowen, First Governor of Queensland’, 1859, Moreton Bay Courier. Tuesday 13 December, p.2

[4] Barton, E J T (ed), 1910, Jubilee History of Queensland, A Record of Political. Industrial. and Social Development. From the Landing of the First Explorers to the close of 1909, H J Diddums & Co., Brisbane, pp.247-9.

[5] Lyman Reed Blake, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lyman-Reed-Blake

[6] Jan Ernst Matzeliger https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jan-Ernst-Matzeliger

[7] Bowden, Bradley and Bradley, Toni, 2004, ‘The Women Do the Machinery': Craft, Gender and Work Transformation in the Brisbane Boot Trade, 1869-95’, Labour History, May, 2004, No. 86, pp.75-92.

[8] R J and R A Sullivan, 1983, ‘The London Dock Strike, the Jondaryan Strike and the Brisbane Bootmakers' Strike, 1889-1890’, in D J Murphy (ed), The Big Strikes. Queensland 1889-1965, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland;

[9] 'Harris, Frederick (Fred) (1870–1942)', People Australia, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/harris-frederick-fred-34072/text42723, accessed 31 July 2024.

[10] Cameron, D B, 1999, A historical assessment of economic Development, manufacturing and the Political economy of Queensland, 1900 to 1930, PhD thesis, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Qld., Table A15.

[11] Cameron, op. cit., Table A29.

[12] Brisbane City Council, Heritage Assessment, https://heritage.brisbane.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/citation/jolly-batchelor-premises-former-_1490.pdf?t=1701255021

[13] Loosemoore, D., David Loosemore’s Family Stories, https://loosemoreblog.wordpress.com/#:~:text=He%20was%20survived%20by%20his,my%20grandmother%20and%20great%2Daunt

[14] ‘Hunter’s Boot Factory’, 1884, Brisbane Courier, Friday 13 June, p. 6

[15] Barton, op.cit., pp. 321-2.

[16] Barton, op.cit., p.321.

[17] Queensland Co-operative Boot Society Ltd., Memorandum and Articles of Association, 1912, Records of the Queensland Cooperative Boot Society Ltd., State Library of Queensland.

[18] ‘Passing Time, Queensland Cooperative Boot Society Ltd., https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2797838733801872&id=1945423115710109&set=a.2407893166129766

Dr Robin Trotter's Research Reveals talk.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.