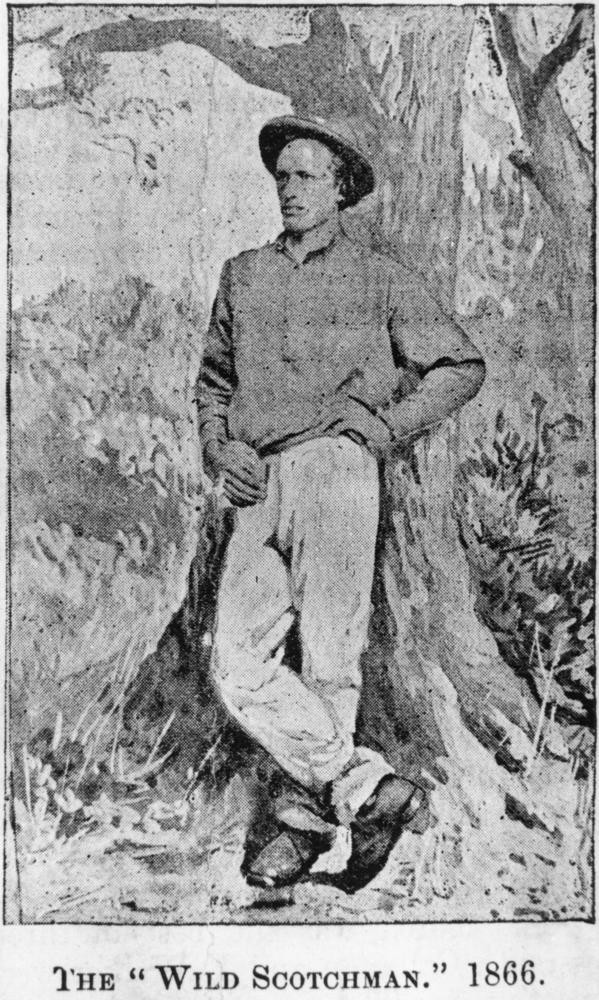

The "Wild Scotchman" : Queensland bushranger James MacPherson Pt.2

By Simon Miller, Library Technician, State Library of Queensland | 1 June 2016

Bushranger James MacPherson, 1866

In Part 1 of the story We followed the career of James Aplin MacPherson, a.k.a. The Wild Scotchman as far as his capture on 31 March 1866 and subsequent imprisonment in Brisbane Gaol awaiting trial. Many in the community were sympathetic towards the dashing young bushranger but others thought he should be treated very harshly such as the author of this letter to The Queenslander.

It is trusted that no maudlin sentimentality will be allowed to deprive the blackguard who has been indulging for the last year or two in the sobriquet of the "Wild Scotchman" of the prize he has been striving so hard to win — viz., a dance in mid-air at the end of a good stout string. By your own journal it will be seen that there is no lack of those who would willingly lionise the vagabond, and that only by strategem was a crowd prevented from gathering to do him honor on arrival at Brisbane. Since his reception in gaol I believe the visitors who pay him court are both fair and numerous. Nothing gives the dear creatures who are privileged to have an introduction, so much pleasure as recognition as old schoolmates ; or an assertion by the outlaw that he knew "that face." When these things are retailed to crowds who have not been privileged by an admission, with the assurance that " he is such a fine-looking fellow, and has a beard as long as that"— bringing the hand very low indeed to suit the action to the word — of course deep sympathy is felt for this " nice young man." Such a feeling is a great misfortune, as if ever a man earned a dance upon nothing the so-called " Wild Scotchman" is that man.

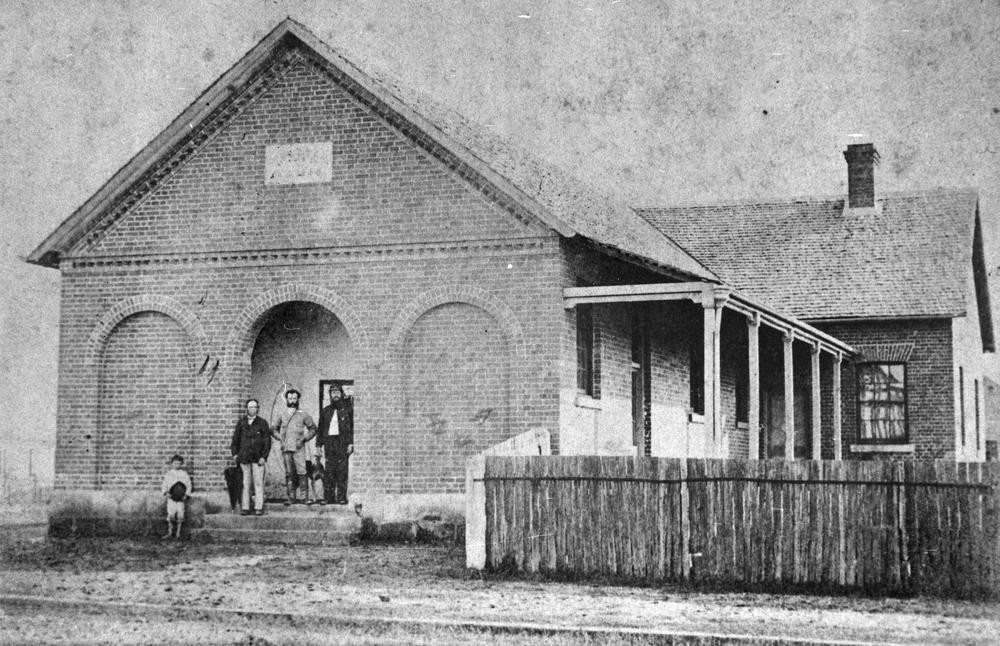

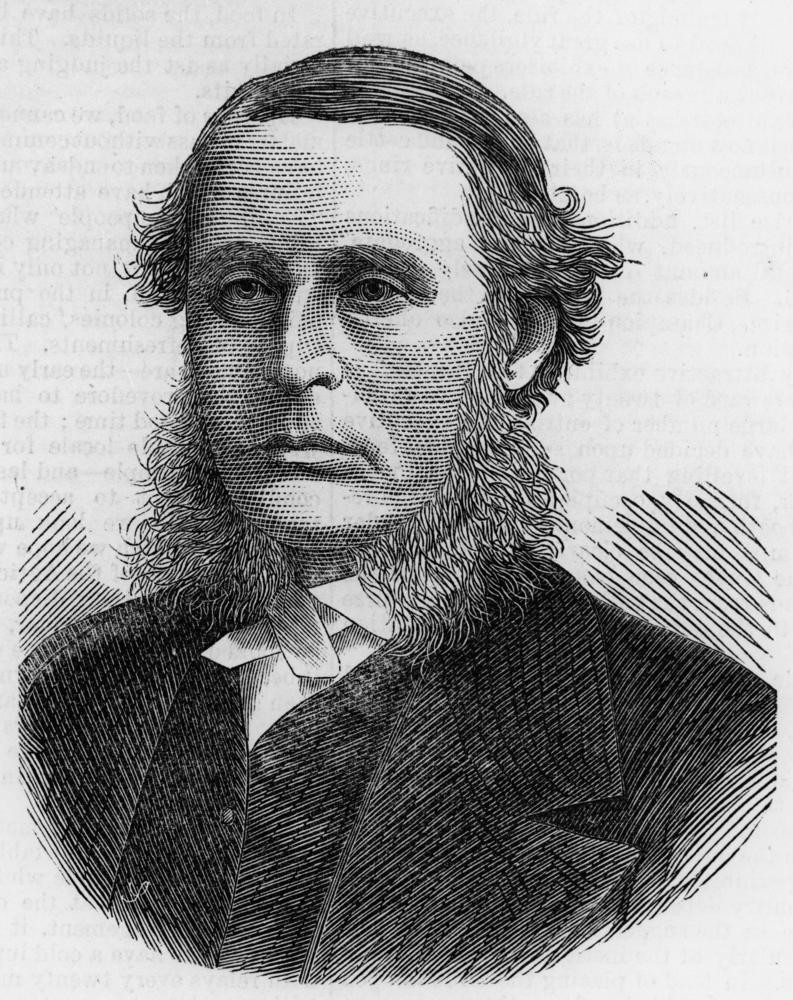

The second part of the story takes us to the courthouse at Maryborough where Chief Justice Sir James Cockle tried MacPherson on two charges that he had on 27 November 1865 and 28 November 1865 robbed Her Majesty's mail and put the mailman in bodily fear.

First courthouse in Maryborough on the corner of Kent and Adelaide Streets, ca. 1872

The trial was covered in detail in the Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser and the report was picked up by other papers around the country. We can skip to the end of the trial and the judge's summing up and sentencing.

On the prisoner being asked if he had anything to say before sentence was passed on him, replied that appearances were certainly against him, but he was not so bad as he appeared. He had once an honourable reputation and good character, and he pleaded with his Honor that he would pass a merciful sentence, so that he might have an opportunity of again leading a life more useful to himself and others than he had lately done.

His Honor said it was with extreme pain that he had to pass the sentence he was about to do on a great strong man like the prisoner, whose life might have been made a credit to himself and useful to the community. But he was obliged to deal with all cases according to the view he entertained of the effect of the punishment on the dangerous part of the community. He regretted be could see nothing in either case to cause him to pass a light sentence. The jury who tried the first case had recommended the prisoner to mercy, which he (the Judge) would have been prepared to accept, but more out of respect for the jury than from his own conclusions on the case. But the jury who tried the second case had not repeated that recommendation. The evidence showed that these were not the only crimes of the kind the prisoner had committed; and if all the circumstances of the two cases had been before the first jury, that recommendation to mercy would probably have not been given. The prisoner appealed for mercy; how could he expect it? He had entered upon a most dangerous course— one affecting vitally the welfare and prosperity of the country. He had taken upon himself to interrupt the communication between one part of the country and another, inflicting in many cases, probably, much personal suffering and loss, destroying trade; and as the example of the neighbouring colony showed, might lead to a great effusion of blood. It was as much the interest of criminals as of the community, that they should be deterred by a severe example from entering upon such a career. Some misapprehension seemed to exist of the state of the law in the colony - the jury in the first case recommending mercy on the ground that no one had been injured by prisoner. He would tell the prisoner, and tell all to whom it might come, that by stopping short of murder the criminal did not render his own life secure. If he (the prisoner) had wounded Hickey, his life would have been forfeited to the law. He hoped it would become generally known that to stop short of murder in this course did not render their own lives safe - that they entered upon it in peril of their own lives. The first jury had called his attention to the circumstance that no actual violence had been shown to be committed. If there had been it would have been his (the Judge's) duty to have sentenced the prisoner to die. To treat leniently this offence on that, account would be preposterous. What prerogative had the prisoner to present fire-arms, loaded or unloaded, at any person? There are many who would prefer personal injury to that. The sentence would not be so severe as it would have been had the prisoner wounded because he should then probably have had to pass sentence of death. On two successive days he (the prisoner) had stopped the mail-the only means of communication, as might be, between portions of the colony; and from the evidence it could be gathered these were not the only two cases of the kind. He had incited the dangerous class of the community to the commission of like crimes, by representing the police and the authorities as too weak to deal with such offenders, and he hoped by the sentence he was about to pass such mistakes would be corrected.

His Honor then sentenced the prisoner to twenty-five years' penal servitude for each offence, the sentences to be concurrent.

Sir James Cockle, first Chief Justice of Queensland

MacPherson entered the penal colony on St Helena Island on 13 September 1866. He was apparently involved in an escape attempt but while a group of prisoners got out of the stockade, they were unable to leave the island and soon recaptured.

Prison guards on St. Helena, ca. 1893

In 1874 a petition signed my many prominent members of Queensland society was presented to the Governor calling for the release of James MacPherson. This report is from the Gippsland Times but attributed the the Rockhampton Bulletin.

The prisoner in this case had, we believe, served eight years of his sentence, and throughout had conducted himself in a most exemplary manner. When convicted he was a mere lad, and never manifested any vicious propensities until he began to read sensational novels recording the exploits of highwaymen in the mother country. This literature poisoned the young fellow's mind, and he deserted his parents, who have lived for many years in the Moreton Bay district, to lead the life of the 'jolly freebooter.' He committed many robberies under arms during his short criminal career, but, fortunately for himself, he never happened to take life. The judge, in passing sentence, stated that it was intended to have a deterrent effect, and was therefore heavier than the circumstances of the crime proved might seem to warrant. The sentence had its effect, for we believe that bushranging has not since been heard of in the colony. The petitioners therefore urged that this was a case for the exercise of the Royal clemency, as well on the prisoner's own account as upon the account of his parents, who, being now aged and infirm, would become a burden upon public charity if deprived of the support of their only remaining son. The old people prayed humbly for his release, and believed that he would henceforth prove not only dutiful to them, but also a useful member of society. We understand the prayer of the petition was supported by the signatures of many members of both Houses of Parliament, and hence no doubt, the favourable consideration it has received from the Acting-Governor.

When he was released, MacPherson returned to the McConnel property at Cressbrook where his parents had worked and was employed as a stockman and overseer of an outstation. Here he came into contact with Sylvester Browne who was the brother of T. A. Browne, better known as novelist Rolf Bowldrewood. It is highly possible that some of the incidents on Bowldrewood's best known book Robbery under arms were based on anecdotes told by MacPherson to Sylvester Browne and then passed on to his brother. MacPherson was well known for entertaining all and sundry with tales of his days as The Wild Scotchman.

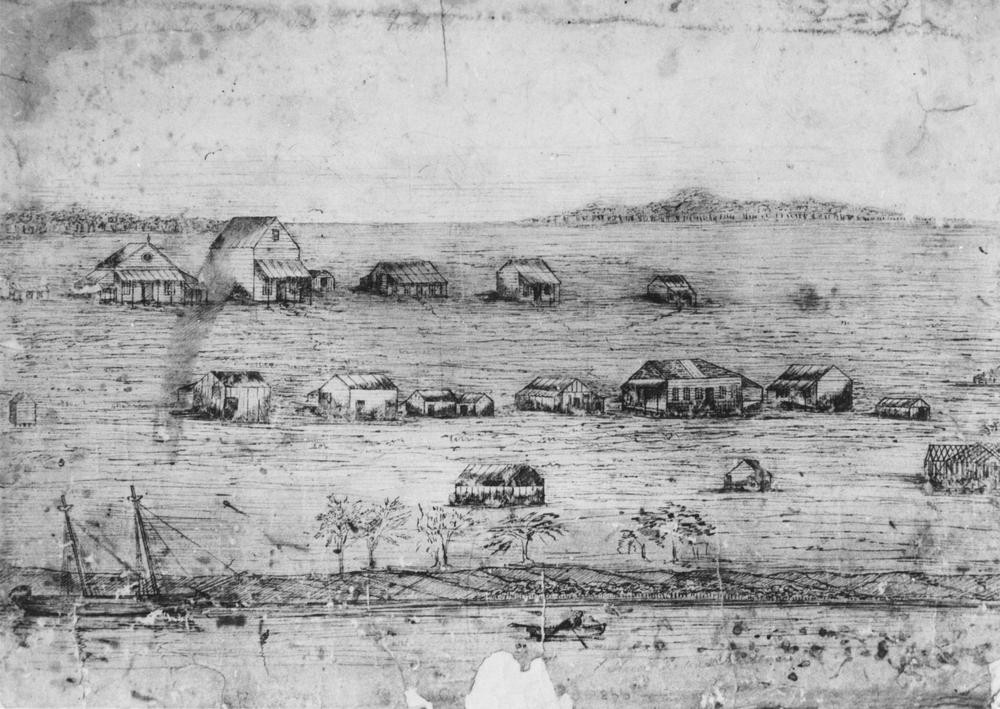

MacPherson married Elizabeth Annie Hasfeldt in 1878 and they produced four sons and two daughters. In 1895 MacPherson was living in Burketown, working in the haulage business. He had always been a superb horseman and it is ironic that his death was due to a fall from his horse. The circumstances were recalled some years later by Mr J.B. Dunn writing to The Brisbane Courier.

I wish to point out, sir, that I was at Burketown when M'Pherson was killed, and it was in peculiar circumstances. A Mr. O'Sullivan, a water carrier at Burketown, was killed by the wheel of his water cart passing over his body, the cart having a load of water on at the time. On the following day O'Sullivan was buried in the Burketown cemetery, on the "Plains of Promise." M'Pherson attended the funeral, and after leaving the cemetery he and his nephew, Steve Hart, had a race to see who had the best horse, and before they had proceeded far M'Pherson's horse fell and rolled over him. That was the last of the "Wild Scotchman," who had married and left a wife and two or three children. He was a very hard-working man during his time in the North.

Sketch of Burketown township, 1886

Perhaps the final word should go to MacPherson's biographer, P.W. McNally, who writes in The life and adventures of The Wild Scotchman:

I wish it to be clearly understood that I do not blame the "Scotchman" for his actions. I blame the society in which he lived, and I feel confident that had he been fortunate enough in his youth to have got into company that would have taken him in hand, and, by a certain amount of restraint - with kindness - kept his buoyant spirit in check, and taught him some trade or profession, he assuredly would have become an ornament to society. The system, as I have stated - not the man - was to blame in those days. It should prove as an object lesson to the youths of the present day.

Simon Miller - Library Technician, State Library of Queensland

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.