Spectacular Entertainments at Edison Lane - Part 2

By Dr Henry Reese, 2021 John Oxley Library Fellow | 20 December 2022

This blog was written by 2021 John Oxley Library Fellow Dr Henry Reese as part of his research into the history of electricity in Queensland.

What sort of world did these early ‘electricians’ inhabit? Much is known of the infrastructure and business life of this time period, but I have found myself becoming increasingly fascinated with the more spectacular, dramatic and sometimes downright bizarre activities of many of the electrical pioneers. They picked up and put down new trends and experimented with provoking public interest in the more romantic and unusual uses of new technologies For instance, you may have heard of Edward Gustavus Campbell Barton, one of the pioneers of the electricity industry in Queensland. The John Oxley Library published an excellent blog post about him in 2019 as part of the Magnificent Makers exhibition. He is a fascinating figure and an important one. Much is known about Barton’s role as a key business and engineering figure, but did you know he also acted as a popular showman?

Barton was at the forefront of global developments in the emerging electrical industry.(1) He studied at the famous Karlsruhe Technical Institute in Germany before taking a job with Siemens in England in the early 1880s. By the early 1880s he arrived in colonial Australia and worked as a contractor on various electrical installations across Australia and New Zealand. (2) He soon settled in Brisbane and in 1888 he went into partnership with the local brothers T.E. and C.F. White. (3) Barton, White & Co. and its successor companies would go on to become one of the most important firms in the provision of electricity in Queensland.

The business clearly tapped into the aura of modernity and spectacle associated with the famous inventors of the day. For example, they famously referred to their main premises in the early 1890s as ‘Edison Lane,’ I think it’s useful to think of Edison Lane as a hive of several different kinds of related activity. These slipped in and out of focus at different times, but ‘electricity’ and ‘modernity’ were always the primary referent. If you like, you can pay a visit to Edison Lane today. It’s tucked away off Creek Street, not far from the iconic Eagle Street Fig Trees. It’s pretty quiet. It’s a much more humble affair today, but you’ll find some great art installations.

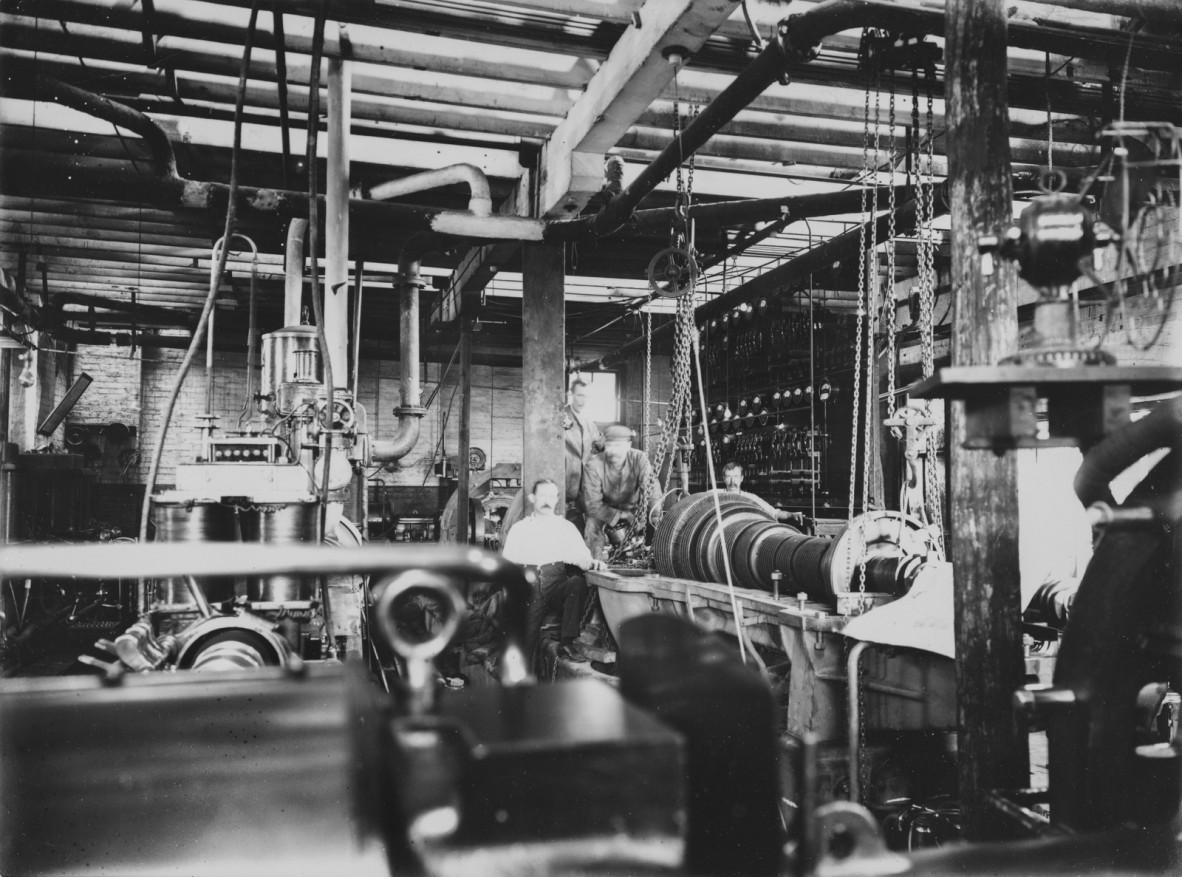

Barton, White & Co.'s Power Station, Edison Lane, Brisbane, ca. 1888. 29572 Queensland Energy Museum Collection, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image number: 29572-0006-0001

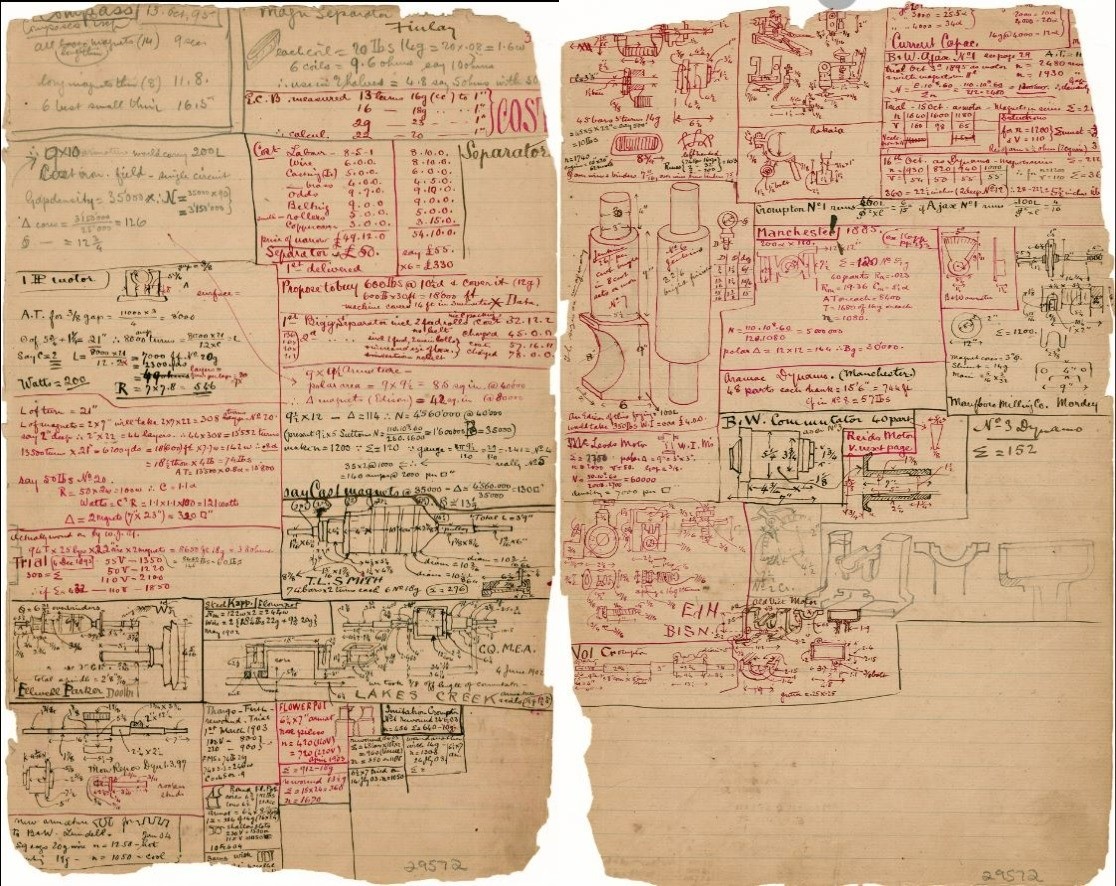

75 loose pages of a workbook belonging to Edward Barton. The pages contain detailed notes, diagrams, formulas, tables, graphs and sketches relating to his business and to electricity supply generally.

29572/76 Edward Barton Workbook. Queensland Energy Museum Collection 1879-1990. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Workshop interior at one of Barton, White and Co.s power stations in Brisbane, Queensland, ca. 1900. 29572 Queensland Energy Museum Collection. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image number: 29572-0006-0006.

Before his electrical business took off, one of Barton’s major side hustles was as a demonstrator of the phonograph. The phonograph was a new machine that recorded and reproduced sound. You’re probably familiar with its more famous cousin, the gramophone. The phonograph wasn’t electrical but it was often associated with other communications technologies like the telegraph and telephone. It was discussed in the same frame of modernity, wonder and energy. It was invented in the late 1870s by — you guessed it — Thomas Edison but only became popular in an improved from in the late 1880s. The technology was extremely rare and prohibitively expensive and there were only a few phonographs in Australasia at the time.

A whole range of scientific lecturers strove to capitalise on the machine’s wondrous connections to Edison and sought to be the first person to introduce colonial Australian audiences to this new machine. They would book out a theatre or a town hall, get up on stage and tell audiences what sound recording was and how it worked. They would then play a series of wax cylinder records for their audiences and sometimes made local records of popular local sounds.

This kind of performance is what the American historian Fred Nadis has called the ‘wonder show,’ a kind of spectacle that crossed the boundaries between science and magic, where performers would ask audiences to reflect deeply on the assumptions they made about their modern world and how it worked. Night after night, audiences across the country were apparently stunned into silence, shocked and delighted by the possibility of sound recording. Just imagine: for the first time ever, it was possible to hear your voice played back to you. It would have been scary, unsettling, delightful. It was possible to hear local sounds that you heard every day, but in a whole new context: they were captured and stored in a modern machine.

Edward Barton and his business partner C.F. ‘Frank’ White weren’t the first people to introduce the phonograph to Queensland audiences, but they were certainly the most prominent figures in this space the early 1890s. By my count, they gave nearly 200 performances in Brisbane and some other Southeast Queensland towns in their most active years, 1891–93.

They first performed in the new Exhibition Building in Bowen Hills, in late August 1891, as part of the annual exhibition of the National Agricultural and Industrial Association of Queensland. (4) In other words, they were a sideshow at the Ekka! Then, from late August to late October 1891, Barton and White set up a parlour in the Courier Building on Queen Street (where the Commonwealth Bank building now stands) and hosted daily performances with their talking machine. The parlour was open from 11am to 10pm, with a one-hour dinner break at 6pm. (5) Audiences couldn’t get enough of it. Before the year was out, they also performed at local shows in Warwick, Beenleigh, Bundaberg and Maryborough.

The spectacles sometimes occurred across different media. In September 1892, the visiting British performer Douglas Archibald — the most famous phonograph lecturer in the Australian colonies — entertained a crowd at the Theatre Royal on Elizabeth Street (where the Myer Centre now stands). Barton and White obtained special permission from the Postmaster-General to run a telephone line from the stage to Parliament House and other nearby locations. An hour’s performance of recorded sound was transmitted through the telephone wires to the Parliament House. (6) Not only did audiences understand the show as performing the most exciting aspects of electricity and modernity, but the show itself also crossed lines between other aspects of the emerging industry.

For the 1893 season, they leased a room behind the Queen Street flower shop of Messrs. E. and R. Grimley, opposite the Opera House (where the Wintergarden now stands). They decorated the space with a selection of loaned paintings and photogravures. (7) The parlour was open from 10am to 10pm. (8) By now, the phonograph parlour was a well-recognised form of high-class leisure:

By 1893, Frank White had begun working as a travelling salesman for a typewriter company and his wide work travels provided a good opportunity for further performances, such as in Charleville, Roma and Stanthorpe.(10) The boundaries between their electrical business and the dramatic world of the phonograph were porous.

By 1893, Barton and White’s repertoire of local recordings displayed at the parlour was wide:

- A rendition of the popular song ‘My Pretty Jane’ sung by Brisbane Tenor C.R. Jones;

- Local composer Edward Lloyd singing his own composition ‘Watching and Dreaming’;

- A constant rotation of new records from America and the southern colonies; and

- Banjo, mandolin and guitar records made by the local musicians Messrs. Martin and Winterflood. (11)

Ultimately, audiences would eventually tire of the new phonograph, and Barton and White’s electrical contracting would take up much more of their time. By the mid-1890s the commercial trade in phonographs and gramophones was becoming established, so it was now possible to encounter recorded sound in new places: shops, pubs, the homes of the rich. So what does Edward Barton’s brief time in the limelight (literally) as a phonograph performer tell us about electricity and modernity in Brisbane?

I think it is an important case study that encourages us to recognise that ‘when old technologies were new,’ in the British historian Carolyn Marvin’s phrase, they were culturally plastic. They meant unexpected things to their audiences. They were used in ways that we would not conventionally associate with them. People experimented in public. They meant a great deal to colonial audiences, who actively, avidly participated in the spectacle of modernity. And finally, this episode illustrates that there were many possible futures for electrical and other technology in Queensland.

I’m looking forward to introducing you to more unusual episodes in the history of technology in Queensland.

…read part 1 of this blog if you missed it.

Dr Henry Reese, 2021 John Oxley Library Fellow.

References

- Hughes, Networks of Power, 142–44.

- Thomis, A History of the Electricity Supply Industry in Queensland: 1888–1938, 1:4.

- Ibid., 1:5–7.

- ’National Agricultural and Industrial Association of Queensland. Annual Exhibition,’ Telegraph (Brisbane), 12 August 1891,

- ‘Edison’s Phonograph,' Courier (Brisbane), 29 August 1891; ‘Phonograph, or Talking Machine,’ Courier (Brisbane), 24 September 1891.

- ‘Telephonography: Loud Phonograph and the Telephone,’ Telegraph (Brisbane), 8 September 1892, 4.

- ‘Phonograph Parlour,’ Telegraph (Brisbane), 5 June 1893, 5.

- ‘The Phonograph,’ Courier (Brisbane), 3 July 1893, 6.

- Phonograph Parlour,’ Telegraph (Brisbane), 29 May 1893, 3.

- ‘The Phonograph,’ Advertiser (Roma, Qld), 13 December 1893, 2.

- ‘Phonograph Parlour,’ Telegraph (Brisbane), 22 July 1893, 5.

Other blogs by Dr Henry Reese

- Researching the history of electricity in the State Library collections

- Spectacular Entertainments at Edison Lane - Part 2

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.