Spectacular Entertainments at Edison Lane - Part 1

By Dr Henry Reese, 2021 John Oxley Library Fellow | 20 December 2022

This blog was written by 2021 John Oxley Library Fellow Dr Henry Reese as part of his research into the history of electricity in Queensland.

We live in a world suffused by electricity and technology. As I type this, right now, a power station somewhere in the state is burning coal to keep my computer running. Electricity is so deeply entwined with our way of life that it’s easy to take it for granted.

Our popular culture has certain prescribed ways of talking about energy and technology. A lot of our discussion is focused on the future. Is AI art ethical? Is geoengineering necessary to avert catastrophic climate change? Will Elon Musk get to Mars?

These kinds of questions and preoccupations are valuable; they can tell us something important about our contemporary preoccupations and assumptions. But it can be easy to forget that our energy sources have a dynamic, contested, complicated history as well.

When you think about the ‘history of technology’ you probably have a few images or ideas in mind. Popular histories often focus on particular things and reflect on their impact in a pretty straightforward, mundane way — what was your first smartphone like? What was the world like before the internet? How did your grandparents get on without a hot water system?

I think these kinds of questions can be great thought experiments. I’ve been teaching history at universities for nearly eight years and I love getting my students thinking about their own personal histories and everyday lives. You probably have an amazing story in mind as you read this.

But focusing too closely on things and their ‘impacts’ can also have a bit of a flattening effect on the way we think about human agency in the past. It’s important that we avoid technological determinism when we talk about new media and new inventions. Technology doesn’t just appear out of nowhere and change the world on its own. Remember that people make history.

Technologies appear and circulate in particular social and cultural contexts, and people shape the meanings and uses that adhere to new technologies using the cultural equipment at their disposal. As the American historian David Nye put it in his classic book Electrifying America,

Media historians emphasise that there is something very personal and intimate about new, modern things. New technologies and media often first appear as ‘local anomalies’ — an encounter with something new, something shocking, perhaps something wondrous or unsettling that forces you to reflect on your daily life, on how your world works and what your assumptions are about it. (2)

So let’s take up these invitations to think deeply about the very intimate, local, everyday context in which people negotiated the meanings and uses of new kinds of technology and energy. What did ‘electricity’ and ‘technology’ mean in Queensland a century ago?

By the closing decades of the nineteenth century, popular discussion of electricity and its uses was everywhere. Colonial society was not as folksy or quaint as popular stereotypes might have you believe. An important field of historical research has emphasised that settlers in late colonial Australia understood themselves as ‘modern,’ and believed themselves to be participating in an up-to-date drama of global proportions. They had high expectations from their culture and they wanted the best in global entertainments. They were curious about the British Empire and the wider world that they were part of. And of course, they participated in and celebrated the processes of settler colonial expansion and dispossession that were intensifying at this time period.

When settlers in late colonial Queensland talked about ‘electricity,’ they usually had a few things in mind:

- communications technologies like the telegraph and telephone;

- electric lighting, which slowly began to spread across the colonies in the 1880s;

- iconic and eccentric inventors like Thomas Edison; and

- various newfangled machines and devices which took up considerable column inches in the local newspapers. These machines weren’t always even necessarily powered by electricity, but they belonged to the same conceptual world as inventors and electricity: automobiles, phonographs, sewing machines, typewriters.

Communications was the field that most vividly demonstrated how ‘electricity’ had already explicitly transformed settlers’ relationships to time and space. If you take even a cursory glance at the local press of the late nineteenth century, you’ll see countless references to news arriving via the medium of ‘the electric telegraph.’ It’s a bit of a cliché today, but historians used to love comparing the telegraph to the internet. (3) Imagine a world newly interlinked by countless miles of humming wires, bringing you information and news from the other side of the world in a matter of days, rather than weeks. The telegraph spread rapidly throughout the Australian colonies in the mid-19th century and quickly became essential. The newly separated colony of Queensland joined the intercolonial communications network in November 1861, when a connection between Brisbane and Sydney was completed near Tenterfield. (4)

Under the vigorous leadership of W.J. Cracknell, Queensland’s general superintendent of telegraphs, a network of thousands of miles of wires quickly spread across the country. By the 1870s, all the major cities and larger regional towns in the colony were plugged into the network, and the technology became a vital aspect of government and business activity. (5)

Steady work over the following decades thickened the network; by 1900 Queensland boasted 422 public telegraph stations, linked by 18,565 miles of wire. (6) And with the famous completion of the Overland Telegraph Line between Darwin and Adelaide in 1872, the Australian colonies were plugged into a global network of news and information. (7) The extraordinary economic boom that Queensland experienced in the 1880s was made possible by the telegraph. Speculators in far-flung mining and business ventures could quickly and reliably source capital on global markets, and British investment poured into the colony. (8)

Lines across the landscape: a telegraph pole in the St. George region, early 20th century. 31188 John Thanasis Tsonakas photograph album of St. George, Queensland. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Adelaide Street Maryborough, looking west, ca. 1904, 4831 Postcard Collection 1900 - 2013. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Neg number 194793.

By the 1880s, the telephone was slowly becoming important as well, although uptake was still limited mainly to business, government and rich and powerful citizens. By 1890, there were over six hundred telephones in use in Queensland, mostly in the urban centres of Brisbane, Maryborough, Rockhampton and Townsville. (9) Telephone exchanges still remained very local affairs at this time though: the first trunk line in Queensland linked Brisbane and Ipswich in 1899. (10)

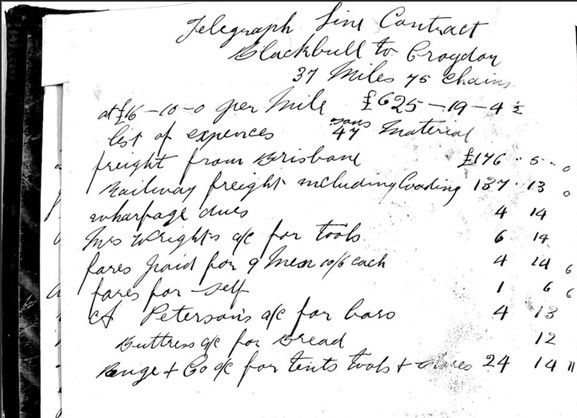

A selection from the ledger and wages book for a contractor working on the construction of a telegraph line from Black Bull to Croydon, August-December 1891. This extraordinary source from the John Oxley Library collections really brings home the huge expenses and back-breaking labour required to construct the new electrical communications infrastructure that underpinned modern Queensland. OM80-31, Black Bull to Croydon Telegraph Records, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

The 1880s also saw the slow spread of other new electrical technologies such as the light bulb, electrical generators and motors. Unlike the telegraph and telephone, however, these innovations remained largely in the hands of private entrepreneurs, investors and manufacturers. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, various business ventures strove to sell these new technologies in Queensland, and various attempts were made to interest the public in the latest products of the famous laboratories of Edison, Bell and Swan overseas. (11)

Electricity was becoming a new source of income and work, often in a very local and everyday sense. For instance, if we flip through a prominent city directory like Pugh’s Almanac (think of it as like a 19th-century version of the Yellow Pages), we will find numerous references to people working in the new industries made possible by this heightened interest in electrical technology.

A new type of occupation that rose to prominence in Queensland in the 1890s was the ‘electrician.’ The role back then usually incorporated a mix of roles: somewhere between what we would today call an electrical engineer, tradesperson and electrical retailer.

For example, if you wanted to install a newfangled electric bell in your business or home in 1890, you could approach three different businesses in the Brisbane CBD: J. Mathieson of George Street, Perry Bros. on Queen Street and James G. Schick on Elizabeth Street. (12) What if you wanted an electric light or generator or some other kind of device? There were three firms recorded in Pugh’s directory in 1890 that could handle this business: the aforementioned James Schick, the famous firm of Trackson Brothers, and Barton, White & Co. (more on them below). (13)

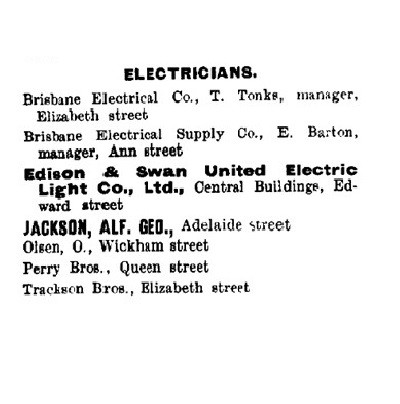

Jump forward ten years to 1900, as recovery was underway from the devastating depression and floods of the 1890s, and there were now seven electricians recorded as offering their services to the people of Brisbane. (14) By this time, the Brisbane Tramways Company was operating nearly sixty electric trams across the city network from its Countess Street powerhouse. (15) Numerous public and private buildings such as department stores, newspapers, theatres, hospitals, government buildings, factories and sporting grounds were lit by electric light. Electricity was having a bit of a moment.

The seven businesses listed in Pugh’s commercial directory as ‘electricians’ in Brisbane for 1900. Pugh’s Almanac and Queensland Directory for 1890 (Brisbane: Gordon and Gotch: 1890), 616. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

So the tumultuous 1890s saw an everyday awareness of electricity spread throughout the population of Queensland. All kinds of commercial ventures were interested in electrical installations in the 1890s. Factories, sugar mills and plantations were interested in lighting and machinery. Local exhibitions, fairs, flower shows and skating rinks often advertised lighting and other electrical novelties like the recently-invented X-Ray as part of their sideshows and attractions. And, increasingly, local governments came to consider the benefits of taking up electrical lighting.

The colonial government soon caught up with the private activities of entrepreneurial electricians like Barton and White and the Trackson Brothers. In 1896, with the passage of the Electric Light and Power Act, the colonial government attempted to provide a framework to regulate the rapid spread of the technology. No longer could you sling up overhead powerlines wherever you could find the space. Now, prospective ‘Electrical Authorities’ had to apply for an Order-in-Council giving them the right to create electrical infrastructure for a given area and a given time. (16) A heated debate about the benefits of public versus private ownership of electrical utilities raged for decades in Queensland, as it did throughout the world at this time. (17)

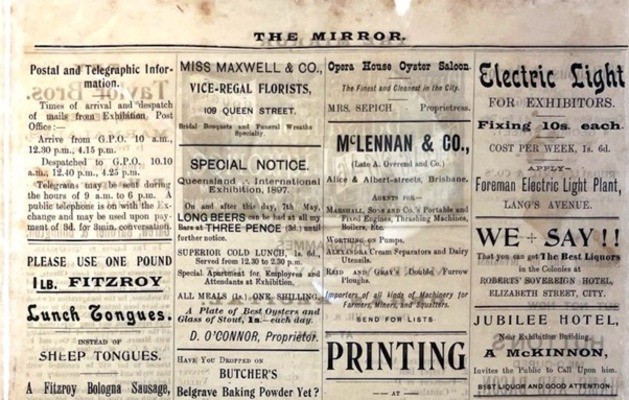

‘Electric Light for Exhibitors’ (top right), an advertisement for the services that Edward Barton offered to the other exhibitors at the Queensland International Exhibition of 1897. This extraordinary source from the John Oxley Library collections gives a brilliant overview of the day-to-day attractions of the Exhibition.

Mirror : the official daily organ of the Queensland International Exhibition, 1897, Brisbane : Australian Publishing and Advertising Co. - W. H. Wendt & Co. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

…this blog continues on part 2.

Dr Henry Reese, 2021 John Oxley Library Fellow.

References

- David E. Nye, Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880-1940 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), ix.

- Lisa Gitelman, Always Already New: Media, History, and the Data of Culture (Cambridge, MA & London: MIT Press, 2006), 29.

- Tom Standage, The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s On-Line Pioneers (New York: Berkley Books, 1999); Alex Nalbach, “‘The Software of Empire’: Telegraphic News Agencies and Imperial Publicity, 1865–1914,” in Imperial Co-Histories: National Identities and the British and Colonial Press, ed. Julie F. Codell (Madison & London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2003), 68–94; Simon J. Potter, News and the British World: The Emergence of an Imperial Press System, 1876–1922 (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

- Ann Moyal, Clear Across Australia: A History of Telecommunications (Melbourne: Nelson, 1984), 23–24.

- Ibid., 27–28.

- Pugh’s Almanac and Queensland Directory for 1900 (Brisbane: Gordon and Gotch, 1900), 55.

- Moyal, Clear Across Australia, 62.

- Ibid.

- Pugh’s Almanac and Queensland Directory for 1890 (Brisbane: Gordon and Gotch: 1890), 62.

- Ronald Lawson, Brisbane in the 1890s: A Study of an Australian Urban Society (Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1973), 7, 14.

- Malcolm I. Thomis, A History of the Electricity Supply Industry in Queensland: 1888–1938, vol. 1 (Brisbane: Boolarong Press for Queensland Electricity Commission, 1987), Ch.1.

- Pugh’s Almanac and Queensland Directory for 1890, 23.

- Pugh’s Almanac and Queensland Directory for 1890, 34.

- Pugh’s Almanac and Queensland Directory for 1900, 616.

- Pugh’s Almanac and Queensland Directory for 1900, 584.

- Thomis, A History of the Electricity Supply Industry in Queensland: 1888–1938.

- Thomas Parke Hughes, Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983); William J. Hausman, Peter Hertner, and Mira Wilkins, Global Electrification: Multinational Enterprise and International Finance in the History of Light and Power, 1878–2007 (Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Other blogs by Dr Henry Reese

- Researching the history of electricity in the State Library collections

- Spectacular Entertainments at Edison Lane - Part 2

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.