Printing Fitzgerald: the Queensland Government Printing Office Under Pressure

By JOL Admin | 7 February 2020

Guest bloggers: Matthew Wengert and Louise Martin-Chew - 2019 John Oxley Library Fellows

Royal Commissions were more common and less politically ‘interesting’ in the early 20th century (for example, a century ago there were half a dozen Royal Commissions in Queensland alone, with a few running concurrently and some lasting only two or three weeks). In the 1970s and 1980s these quasi-judicial inquiries became longer, rarer, and increasingly dramatic. With their growing size and the raising of the stakes of these public inquiries, their public face has been inextricably linked with their Commissioners. These individuals have been tied, in both the public mind and by government, to their inquiries and reports. In recent years we have had Woodward (1973-74 Aboriginal Land Rights), Costigan (1980-84 Painters and Dockers Union), Stewart (1981-83 Drug Trafficking), McClelland (1984-85 British Nuclear Tests in Australia), and recently Hayne (2017-19 Banking and Superannuation Misconduct) to name a few.

The Commissioners took on a not-always-welcome level of celebrity. Tony Fitzgerald QC had little public profile when he was selected to explore the corrupt political underbelly and decades of police misconduct in Queensland political life (1987-89), but appeared to grow comfortable with a leading role in the closely and widely watched drama. As the hearings and investigations gathered pace, and particularly after the first prosecutions began, it was clear that this new broom was going to sweep away many shady characters and the activities they had profited from for so long. The ‘Fitzgerald Inquiry’ remains a paradigm exemplar for the Royal Commissions that followed.

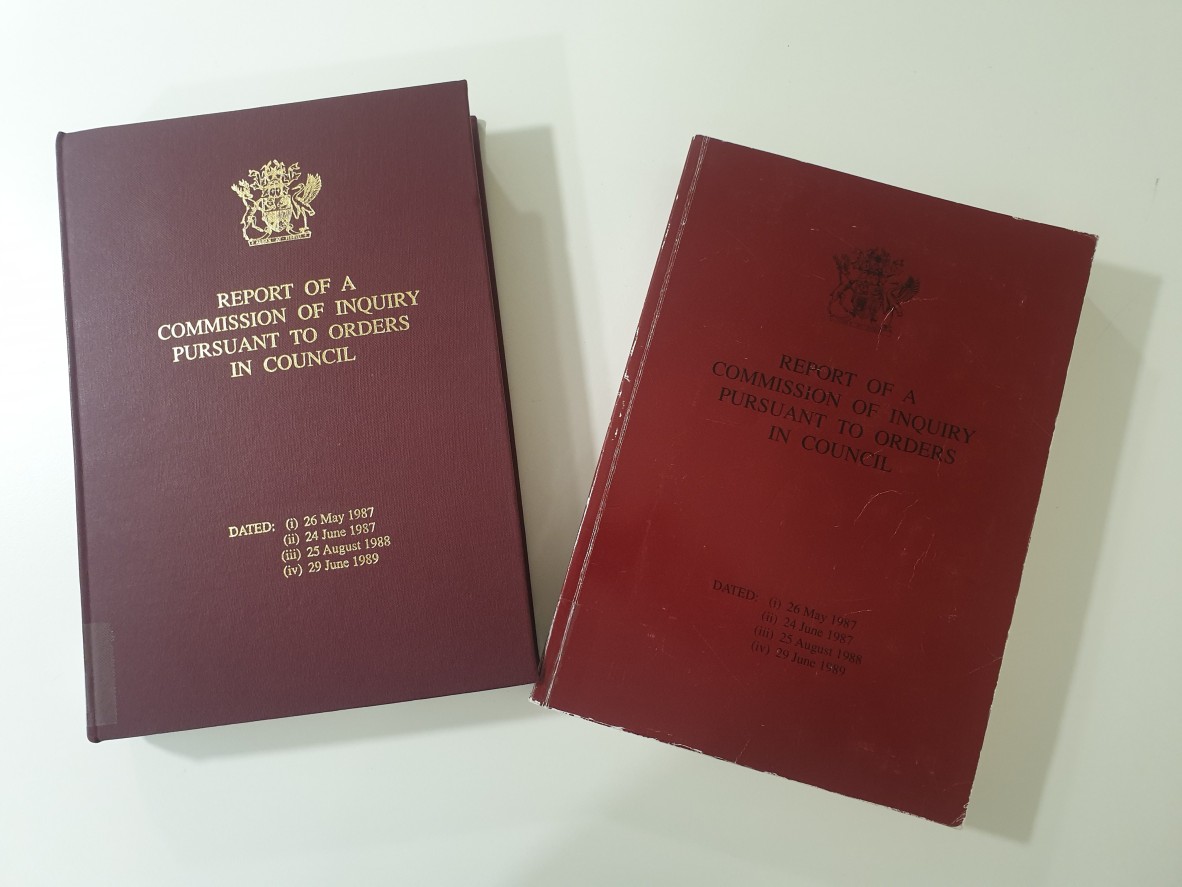

‘Fitzgerald’ was formally titled The Commission of Inquiry Into Possible Illegal Activities and Associated Police Misconduct––a title which lurches and stumbles, rather than rolls, off the tongue. It was announced in May 1987 in the immediate wake of Phil Dickie’s articles for the Courier Mail and Chris Masters’ Four Corners episode––‘The Moonlight State’. The Fitzgerald Inquiry commenced in July 1987, and the report was finally published and tabled in Parliament in July 1989. The report lists four dates on the frontispiece––the final was printed on 29 June, and it was presented to Premier Mike Ahearn and Police Minister Russell Cooper on 3 July.

For two years the public appetite had been whetted by morsels of information pertaining to the level of long-suspected corruption that had infected Queensland’s institutions and government; Fitzgerald was a feast of the minutiae of this infection, details on 400-odd pages of the printed report. It quickly became a best-seller.

In the interviews we have conducted as part of our John Oxley Fellowship, we have been struck by a consistent theme expressed by former QGPO staff: the Printing Office (and later GoPrint) was a lively workplace, and often the scene of fun and games, but the ‘devils’ were proud to deliver high quality printing jobs on time. They met their deadlines and honoured the highly confidential nature of what they saw. Many of their tasks were time-critical, and sometimes they were given big jobs with very tight demands––but they got the jobs done

The Fitzgerald Report acknowledged the role of the office and its staff:

"The Commission expresses appreciation of the part played by the Government Printer, Mr. S.R. Hampson and the staff of GOPRINT in the production of the printed copies of the Report under conditions of the utmost confidentiality to meet critical deadlines."

Although this report is popularly known by just the surname of the Commissioner, the massive workload obviously required a considerable team, as noted in the report’s preamble:

"As at the end of June 1989, the total personnel of the Commission was a Commissioner, two Deputies to the Commission, one Senior Counsel, four other members of the private Bar, six lawyers engaged on contract (formerly public servants or prosecutors within the office of the Director of Prosecutions), one lawyer from the public service, four accountants, five research consultants and assistants, a Clerk to the Commission, the Secretary to the Commission and five administrative support staff, three investigative support officers, five information retrieval officers, two computer systems officers, a receptionist, twenty-two secretarial/keyboard staff, and seventy-five police officers."

Given its importance to the state of Queensland and the seismic shift it created in the political foundations of decades of government, QGPO employees remember well its passage through the printing office. Scott Albury began work at the QGPO as an apprentice, and rose to be Government Printer (and was in that role when GoPrint closed in 2013). In an interview in December 2019, he recalled:

"I was in typesetting at the time , in the pre-press area, and we worked 14 days straight to get this thing done. I remember how big it was, how much work. We worked Saturdays and Sundays to get it done. I played football then and I missed a Sunday game because when I said, ‘I can’t come in tomorrow, I’ve got football,’ they said, ‘Oh, shit, we’ve got to get this thing done.’ It was just such a big project, and obviously sensitive and they didn’t want it leaked, and it had to be out quick. We were still typesetting it at that stage. … and then when we finally printed it, I remember people lining up at our publications office to buy the report. We couldn’t print enough––people kept lining up to buy it."1

Another ex-QGPO employee, Danny Dougherty, an apprentice in 1989, told us:

"That was a very thick report. Once the report was ready to go to print we worked basically 24 hours a day to get the job done. I think it was due to be released on a Monday or Tuesday, and we worked the whole weekend. I remember Tony Fitzgerald brought his family through to look at the process. We did a soft copy, and then we did a hard copy in leather binding for Tony Fitzgerald and senior politicians. And that was an incredibly sensitive report. It wasn’t the sort of thing where you could stand at the end of the machine and start reading it––that was certainly frowned upon. We did three or four reprints–it was so popular. The place was a hive of activity, there was lots of security around that report, you couldn’t get in or out of the building without signing-in and signing-out. It was exciting to meet Tony Fitzgerald. I was working away and the guy who wrote the report was wandering through the factory with his family.2"

Ted Faulkner, who worked at the QGPO from 1976, was involved in printing parliamentary material like Hansard. He was all too aware of the importance of efficiency and security.

"That was one of the things the Government Printer was proud of, and we were too––the security. There were no leakages. There were very important things going through. With Fitzgerald, everything was pretty tight-lipped. I was interested, so I would have liked to read some of it. And you could read it as you were printing it, but you couldn’t go outside the place and say anything about it. And we didn’t. The security was unbelievable."3

Another ex-employee, who prefers not to be named, recalled that high ranking police officers were being arrested as the report came off the press, and that there was a level of personal risk to anyone associated with the report, with threats made to QGPO individuals and their families. The Fitzgerald stakes were amongst the highest that the QGPO witnessed in its one hundred and fifty-one years of operations.

The State Library of Queensland has numerous original items relating to the ‘Fitzgerald Inquiry’––including photographs, and manuscript material:

- OM95-43 Fitzgerald Inquiry Clippings 1987-1990

- 27051 Tony Fitzgerald Collection 1984-2009

- 3215 Peter Beattie sketch 1988

- 31218 Lyn Croxon Works of Art 1988-1989

- 27307 Phil Dickie Collection 1964-1989

The Fitzgerald Inquiry is also an important ‘Q150’ Icon.

Matthew Wengert and Louise Martin-Chew - 2019 John Oxley Library Fellows

References

- Scott Albury Interview, conducted by Matthew Wengert, December 2019.

- Danny Dougherty Interview, conducted by Matthew Wengert, July 2019.

- Ted Faulker Interview, conducted by Matthew Wengert, August 2019.

Do you have a Queensland story to tell?

Applications are now open for the 2020 State Library of Queensland fellowships, awards and residencies. If you have an interest in applying but are not sure where to start, come along to the fellowship information night. Hear from a panel of past fellows, judges and State Library staff to learn how to kick-start your application. All applications must be received by 5:00pm Thursday 26 March 2020.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.