‘It was their baby’: Land ballots and the Fitzroy Basin Brigalow Development Scheme

By JOL Admin | 2 May 2019

Guest blogger: Dr Jennifer Moffatt, 2018 John Oxley Library Fellow.

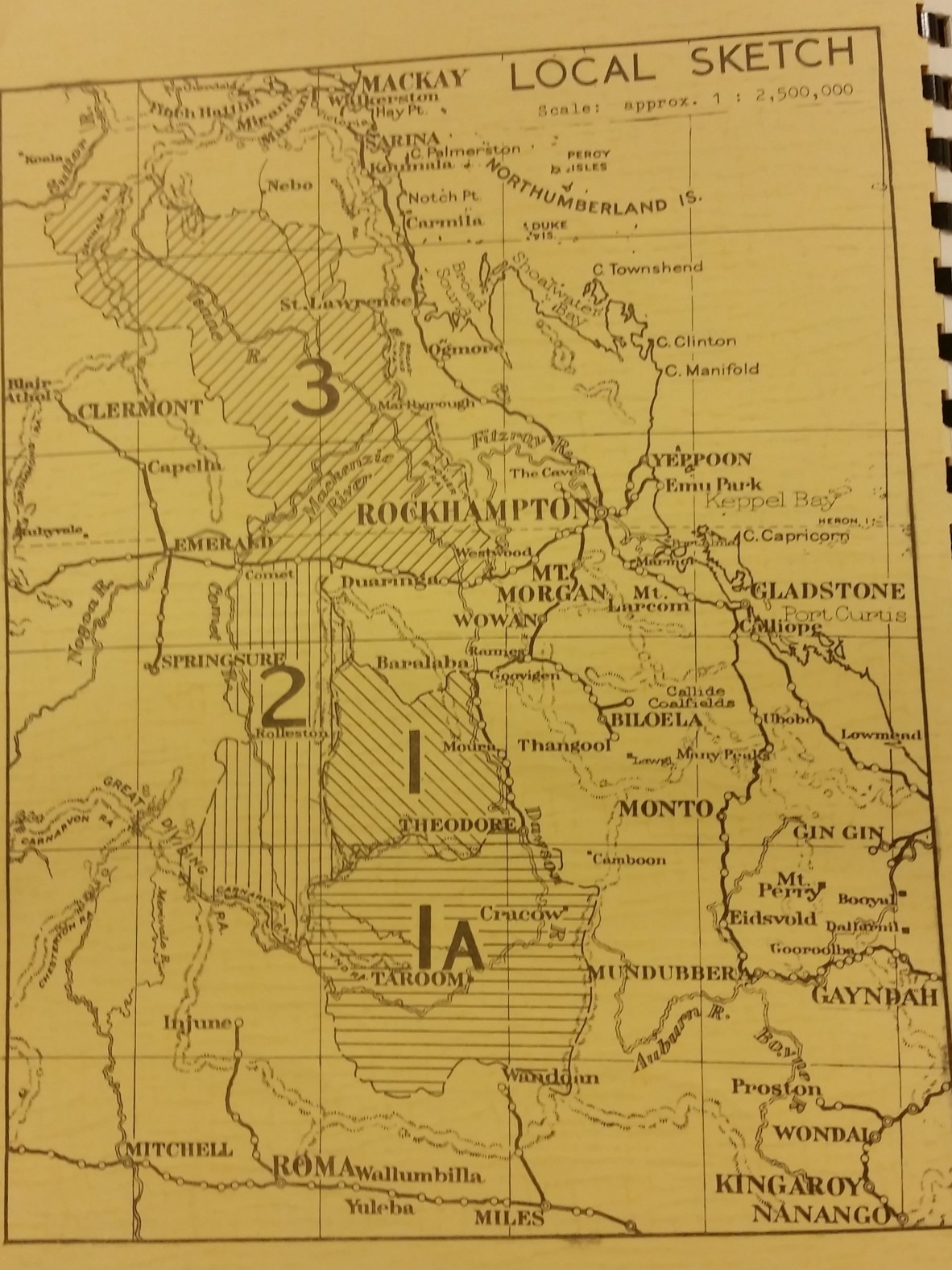

The Fitzroy Basin Brigalow Development Scheme, or the Brigalow scheme as its known, is among the largest land development schemes undertaken by the Queensland government. The scheme was comprised of Crown land resumed from existing lessees which was sold or balloted, portions returned to those who it was resumed from, reserves and roads 1. Seventy-five per cent of the land made available, or over 1 million hectares, was balloted1.

The risk

The Queensland government borrowed $23 million from the Commonwealth to develop 4.52 million hectares of the brigalow belt from 1963 and 1976 1. This was converted from predominantly dense tree coverage to highly productive beef and some grain businesses – the scheme goal. One of the balloters interviewed for the Land ballot project, described the scheme as ‘their baby’ 2. This captures the awareness of several interviewees of the importance to the Queensland government for this investment to succeed – the large Commonwealth debt. A component of this debt was in loans to balloters to develop their land, a risk not previously undertaken by the Queensland government. The close attention paid to the scheme is illustrated by impromptu visits to balloters by Ministers and senior public servants, the close involvement of locally-based staff, operational support from government departments, a debt moratorium when the cattle market slumped, and flexibility around the timeliness of lease conditions being met 3.

The scheme

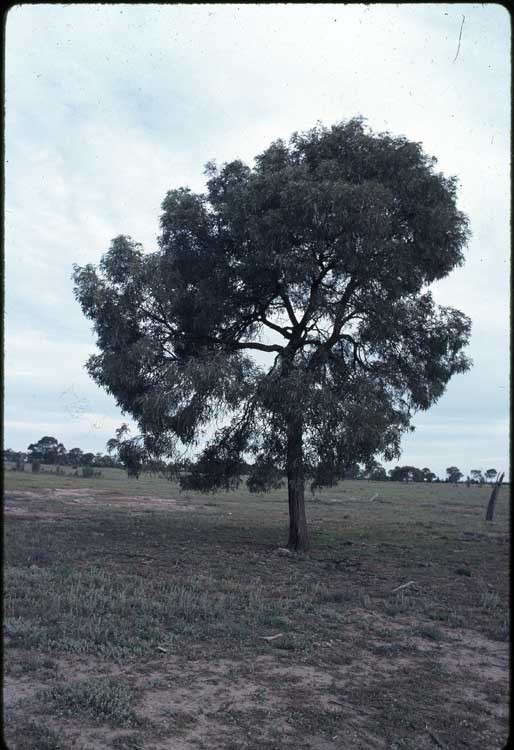

The brigalow belt covers an area of approximately 23 million hectares between Collinsville and Goondiwindi then into New South Wales, about 320 kilometres wide, in a rainfall area of approximately 328 to 573 millilitres per year4. The scheme name comes from the dominant vegetation, the brigalow tree or Acacia harpophylla 5. While there were a number of reasons for this particular scheme, the driving force in land settlement for the Queensland government was to maintain a healthy balance of payments and at this time primary produce accounted for 82% of Queensland’s overseas exports 6. So the primary purpose was to convert this area into one that produced income for the Queensland government. Additionally, this scheme illustrates the Queensland government’s long-standing land settlement policy established in 1894 which was to convert all suitable land to individually owned agricultural farms 7,8.

Due to the rationale for the scheme being to increase production, the scientific research of interest was on the land’s capacity to increase agricultural production. The gains were estimated to be up to a 550% increase in beef production tonnage 9 but this required large-scale land-clearing 4,9. While there were active conservationists in Australia from the late 19th century, it wasn’t until the 1970s that the environment movement captured the public’s attention 10. For resources about land ballots and this scheme search on the tags ‘land ballots’ and ‘brigalow’ under ‘tags’ in the State Library of Queensland's One Search catalogue. To contribute to the project contact the State Library of Queensland qldmemory@slq.qld.gov.au or via jennifermoffattconsulting.com.au

1 Queensland Land Administration Commission Fitzroy Basin, The brigalow scheme in Central Queensland 1962-1978. 1979, Land Administration Commission Department of Lands: Brisbane. (©State of Queensland, 1979 CC-BY 4.0).

2 Balloter in the Springsure Rolleston area interviewed for the Land ballot project. 2018.

3 Balloters in the Springsure Rolleston and Taroom areas interviewed for the Land ballot project. 2018.

4 Skerman, P.J., The brigalow country and its importance to Queensland. Australian Institute of Agricultural Science, 1953. 19: p. 167-76.

5 Atlas of Living Australia. Acacia harpophylla F.Muell. ex Benth. ; Available from: https://bie.ala.org.au/species/http://id.biodiversity.org.au/node/apni/2887238#overview.

6 Land Settlement Advisory Commission Queensland, Report on progressive land settlement in Queensland (Payne report), W.L. Payne, Editor. 1959, Government Printer: Brisbane.

7. Queensland Royal Commission on Pastoral Lands Settlement, Report of the Royal Commission appointed to investigate certain matters relating to the pastoral industry in Queensland. 1951, Government printer: Brisbane.

8The Crown Lands Act of 1884 consolidated, in 48 Vic. 1884: Australia. (© The State of Queensland (Office of Queensland Parliamentary Counsel), 2018 CC-BY).

9 Bureau of Agricultural Economics, The economics of brigalow land development in the Fitzroy Basin, Queensland, Dawson Range to Comet River, and Mackenzie-Isaac River basin, total area 9.5 million acres. 1963, Bureau of Agricultural Economics: Canberra.

10 Hutton, D. and L. Connors, A History of the Australian Environment Movement. 1999, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jennifer’s project is titled: The story of Queensland’s selectors. How those who won land in a ballot contributed to Queensland’s social, economic and political development. The aim is to fill a knowledge gap in Queensland’s history to complement the history of pioneers, squatters and land development.

Jennifer will be presenting her research at the Research Reveals talks on Thursday 8 August, 2019 at State Library of Queensland. Bookings are essential. Free event. All welcome.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.