The great "tin rush" of Stanthorpe

By Christina Ealing-Godbold, Research Librarian, Information and Client Services | 15 December 2014

The 1870s saw a great rush to mine alluvial tin in a place called Quart Pot Creek on the Darling Downs. This rural locality, 170km south-west of Brisbane, is now known as Stanthorpe, named after the Latin word for tin, stannum. Geoscience Australia records that Tin (Sn) is one of the few metals that has been used and traded by humans for more than 5,000 years. One of its oldest uses is in combination with copper to make bronze. Tin has the advantageous combinations of a low melting point, malleability, and the ability to alloy with other metals. Tin is almost always found closely allied to the granite from which it originates, hence the discovery of tin in the Granite Belt region of Queensland’s Southern Downs.

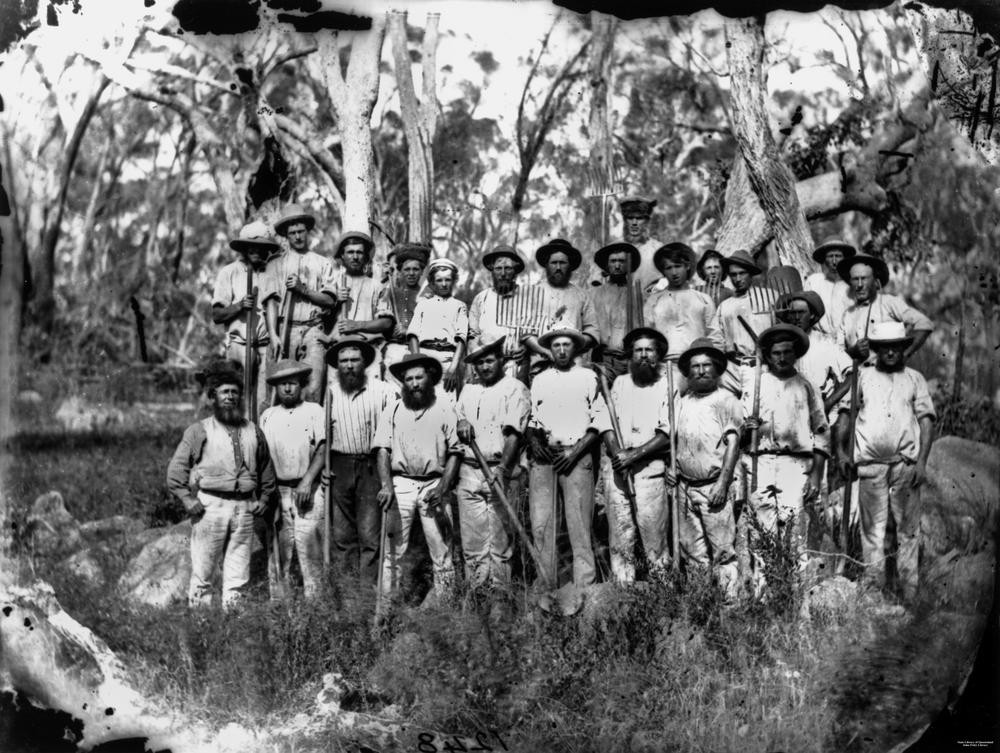

Tin miners near Stanthorpe, ca. 1872. Photograph by William Boag. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative No. 20171 http://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/208631

Tin was first discovered in the Stanthorpe area in 1852, but was not actually worked until 1872. The area was a quiet backwater, with several pastoral runs and shepherds’ huts dotting the landscape. The Pioneer Tin Mining Company started mining at Stanthorpe in 1872, putting the place on the map. With the global boom in tin prices in the 1870s, prices rose by 20 pounds per ton. Intermittent booms occurred in subsequent years. With tin found along the watercourses, streams and creeks, the region quickly became the largest alluvial tin mine in Queensland. In 1874, Mr Miles MLA said that “the district of Stanthorpe had contributed more largely to the prosperity of Queensland than any other district in it.” Tin valued at 2.5 million pounds was reportedly produced from the area. Commercial mining operations continued in the area for over 60 years.

Miners working at St. Leonards Tin Mine Sugarloaf Creek near Stanthorpe ca. 1873. Photograph by William Boag. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative No. 159741 https://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/110207

The tin miners came from many different backgrounds, including Chinese. Tin mining began in Queensland’s north, around Mt Garnet and the Palmer River, but when substantial deposits were discovered near Stanthorpe, a stampede of European and Asian miners made their way south. In fact, The Warwick Examiner reported in February 1872, "There is a great stampede to the district, parties on horseback, as well as large numbers on foot, with swags before them ... Cobb and Co coaches commenced running services twice a day from the railway terminus in Warwick. Passengers clung precariously to every available part of the coach. Express coaches were run." Goods started coming by teams, and saddle horses were advertised to ride to the diggings. In May, The Warwick Examiner said, "the invasion of tin hunters still arrive in a countless host. All labour which arrives seems to be absorbed."

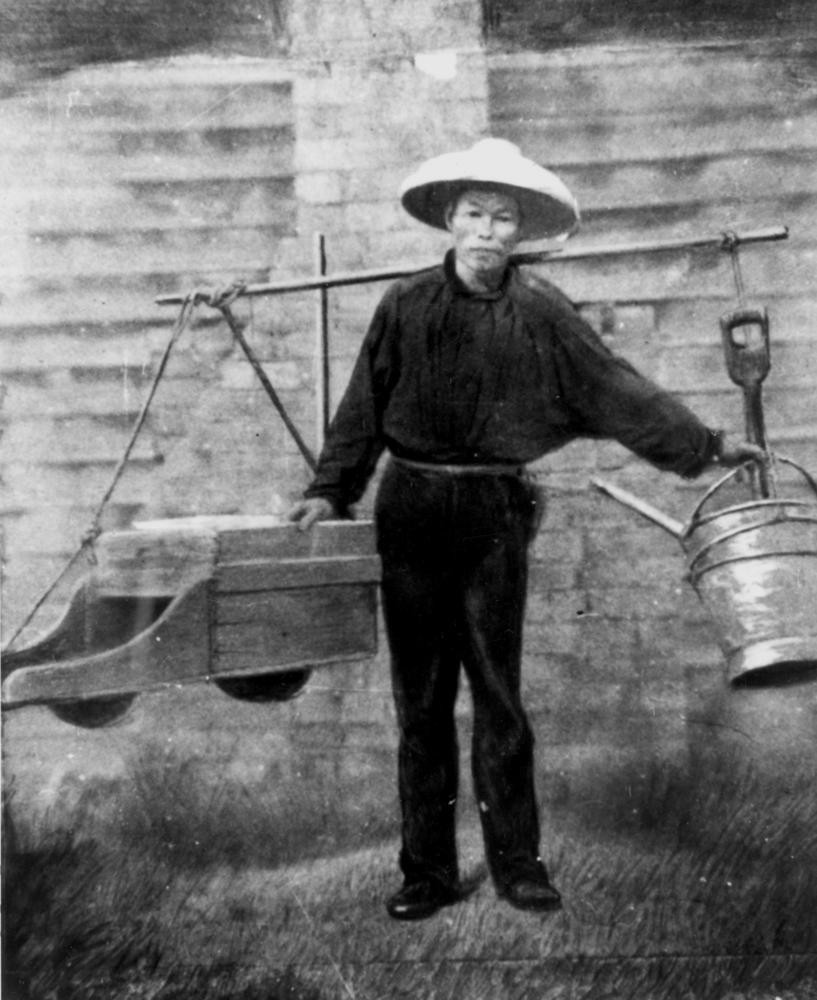

It appears that Chinese labourers were arriving by ship into the Port of Brisbane, taking the train or other land transport to Warwick, and then making their way out to the tin fields. There was apparently an agent for Chinese immigration in Queensland called Mr Bauer. According to The Queenslander newspaper of 12 September 1874, “the immigrants were drawn from the ports of Amoy and Swatow, north of Canton and near Formosa (now called Taiwan) and were of very industrious habits. They were indentured for a period of 5 years, working 6 days a week, 9 and 1/2 hours per day, and were to be paid 7 dollars per month. The agreement included food (8 oz meat per day), a suit of clothes and a blanket yearly, free medical attendance and in the case of incurable illness, 50 dollars to pay the return passage home. The agreement was identical to that provided to Chinese labourers who engaged to work on the plantations of the West Indies.”

Chinese gold digger starting for work ca. 1860s. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative No. 60526 https://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/134556

The Chinese arrived by train in Warwick and were reported as "long strings of celestials making their way to the mines." The European settlers were not happy, and complained in 1873 because the Chinese were willing to work for a lower wage and "worked on tribute", which meant that they willingly worked on alluvial deposits where locals had already lost money or given up hope of finding more tin. It was reported in 1875 that, in some cases, the Chinese were making from half an ounce to one ounce per day of tin in ground that was abandoned by white miners as being “not payable”. In 1877, there were continuing reports in the press of “two hundred Chinamen going up the line, en-route for the tin mines.” In 1877, there was even mention of a shipping line being established to bring the Chinese labourers directly from Hong Kong to Brisbane. One example given was the ship “Killarney”, which arrived in 1875 with 500 passengers bound for the tin fields.

Chinese merchants in the Darling Downs, ca. 1875. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Nevagtive No. 63654 https://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/138403

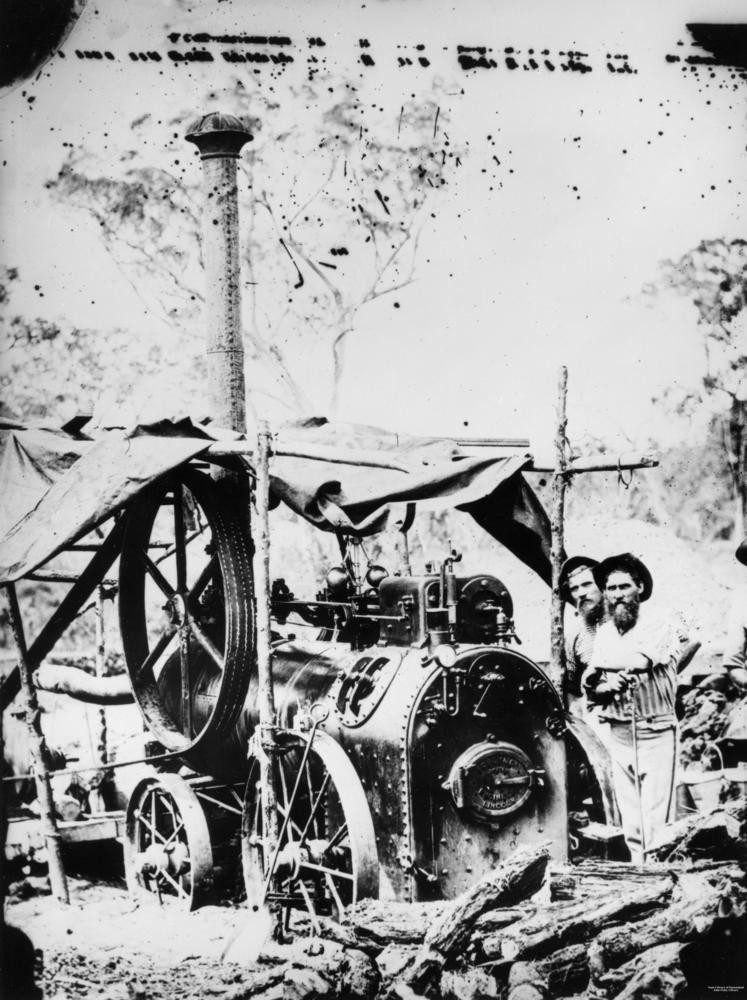

Tin mining was not an easy task. An early Queensland photographer, William Boag, spent time in Stanthorpe in 1873 and took some wonderful black and white glass photographic negatives of the tin miners, which are in State Library of Queensland’s collection. Although in many parts of the tin fields a prospector might discover a few grains of tin in a pie dish full of sand scooped up near a creek, other speculators cut trenches into the ground in pursuit of walnut-sized pieces of ore. Other miners used earth augers, worked by two men, to prospect for alluvial tin. The auger enabled mining to a depth of 35 feet, even in the wettest soil, as the tin was contained in seams along the creeks. Portable steam engines were also used, as the Boag photographs demonstrate. The steam engine was used to drive a water pump, which drained the workings or helped with the task of sluicing. It was a small four-horse power model that was fired with wood and was protected from the weather by a makeshift shelter covered with a canvas tarpaulin.

Prospectors next to a portable steam engine ca. 1870. Photograph by William Boag. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Negative No. 71969 https://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/68174

The Queenslander reported that nearly all of the tin was gone by 1892, and that, in its heyday, “Stanthorpe had about thirty hotels all doing a roaring trade, its streets at night were thronged with moleskin-clad miners, its trade for many years was enormous; but gradually the rich stores were exhausted, until now it may be said its tin-mining is almost ended.”

Who would have thought that Stanthorpe, now known for its wine and cool climate fruit, was the centre of a mining rush, and that many Chinese labourers came to this inland place from coastal areas of China to make their fortune? Some stayed to become part of the fabric of an iconic Queensland town.

Christina Ealing-Godbold, Senior Librarian, Information Services.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.