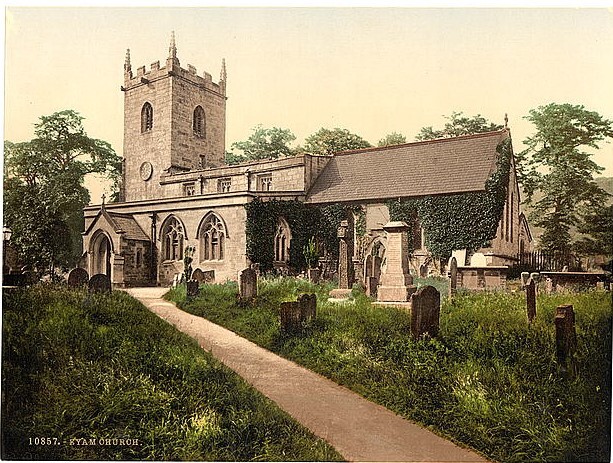

This idyllic scene of 19th century Eyam was very different when the plague struck nearly two centuries earlier.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eyam_village_19C.jpg

The story of the plague in Eyam

In September 1665 a collection of patterns was sent to the local tailor of Eyam, Derbyshire. His assistant dried the wet bundle in front of a hearth. In this way, it is believed, the plague spread rapidly through the village as the heat activated the plague carrying fleas from disease ridden London. Bubonic plague, its symptoms and dire consequences were well known and dreaded. The unpopular, distrusted rector William Mompesson wanted to quarantine the village to prevent the spread to neighbouring villages and was willing to support the people in every way, even at the cost of his life. He turned for help to the previous rector, Thomas Stanley who lived on the edge of the village and whom the villagers respected. Stanley was a supporter of Oliver Cromwell and the Puritans at a time when it was widely politically unpopular to do so, but he provided essential cooperation.

The Earl of Devonshire at nearby Chatsworth agreed to send all necessities to the villagers if they agreed to quarantine. Despite their fears and doubts, they agreed. Heavy stones were placed around the village. No one could travel out or in beyond that point. Food was left at the village edge and money was cleaned in vinegar to pay for it.

The results were predictably devastating. In August 1665, a very hot summer made the fleas more active and encouraged the spread of the plague to the point that the death rate was six a day. Elizabeth Hancock buried six children and her husband over a period of eight days near the farm. The graveyard had been filled. Those from a nearby village watched her, too frightened to assist.

Eyam Church, Derbyshire, England, ca.1900, Photograph.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsc-08309, https://www.loc.gov/item/2002696679/.

Marshall Howe, an early survivor of the plague, believed he had become immune and buried the dead. He took their possessions which may have been contagious to his wife and two-year-old child who died. William Mompesson’s faithful wife Catherine, who supported him through this terrifying experience, caught the disease and died aged twenty-seven on 22 August. By November the plague was over. Thirty-six percent of the population of Eyam had died but the neighbouring areas were saved.

Catherine Mompesson’s grave, By mickie collins, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9197454

In 1669 when Mompesson went to a Nottinghamshire village he had to live in a hut away from the centre for some time because of the fear that he might have brought contamination from Eyam. He paid a terrible price for his principled stand.

Relevance today

Eyam’s plague is a puzzle many are trying to analyse. Sheena Cruickshank, professor in Biomedical Sciences at the University of Manchester, said:

"Learning about our history with disease informs our future. We know the immune system combines with other factors - the strength and dose of the pathogen, the health of the individuals, relative isolation - to determine the severity of the epidemic. Some factors: living in proximity to animals and affecting animal habitats, still play a role today. Eyam is a snapshot of how one community was shaped by, and itself shaped, the spread of a disease. And it is possible that survivors with more effective immunity led to part of the immune system of the survivors being selected for and handed down to following generations."

The bacterium causing the plague was not identified until 1894. Today there are still parts of Africa, India and the United States which experience outbreaks.

Dr Whittles, infectious disease modeller at Imperial College London, said:

"Eyam is important because it gives us fantastic data for the plague. We know about individuals, about households and particularly when people died. In larger populations, like in the cities, you only get weekly death tolls, which don't allow you to look at the finer patterns at the individual level. With the information from Eyam you can track how the disease is most likely to have spread. It has been understood, classically, that the plague spread from rat to human via the flea. We found human-to-human transmission during this outbreak - especially within families - was a much bigger factor than previously thought. The main lesson here is that before imposing control measures to stop the spread of an infectious disease, it is essential to understand the way it spreads. There is often more than a single route of transmission, in which case it becomes important to estimate the relative importance of the various routes. Records also showed children and individuals living in poorer, untaxed households suffered most, still relevant today."

Find out more about Eyam via the State Library’s catalogue including:

- images and articles on Eyam and the plague as well as specific items on studies of disease

- reviews of Geraldine Brooks novel, Year of Wonders, a successful novel about the Eyam plague.

- Jill Paton Walsh’s fictionalised account of the Eyam plague disaster, A parcel of patterns, for children and young adults, timely reading for today, available at State Library.

What will be the lessons from our current pandemic experience?

Acknowledgements:

- "Eyam plague: The village of the damned" by David McKenna BBC News, which provided some essential facts

- "Coronavirus: What can the 'plague village' of Eyam teach us?" By Greig Watson, BBC News; for the expert opinions quoted.

Check these sites for more information and powerful images of the Eyam experience.

Stephanie Ryan

Research Librarian, Information Services

More information

Ask us - /plan-my-visit/services/ask-us

Library membership - /get-involved/become-member

Onesearch - http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.