Enemy Alien: what it meant to be a German-born Queenslander during World War One

By Eileen Dwane, Librarian, Information and Client Services | 31 August 2021

In Queensland - where most of the population could claim British heritage - the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914 was met with a rush of patriotic fervour in support of ‘Mother England and her sons’. How did the wave of anti-German sentiment that accompanied this patriotic fervour impact the lives of Queenslanders with German heritage? Librarian Eileen Dwane delves into our collections to find out.

Place-name changes

Authorities throughout Australia rushed to change place-names that had any association with Germany.

Pugh’s Almanac of 1917 noted that the names of 10 towns had been changed during the previous year:

- Bismarck to Maclagan

- Engelsburg to Kalbar

- Friezland to Kurilala

- Gramzow to Carbrook

- Kirchheim to Haigslea

- Hapsburg to Kowri

- Kessenburg to Ingoldsb

- Marburg to Townshend

- Steizlits to Woongoolba

- Teutoberg to Witta

The names of numerous streets and suburbs were also changed.

In 1916 the Townsville suburb of ‘German Gardens’, originally named to honour a German settler who had established a vineyard there in the 1860’s, was renamed ‘Belgian Gardens’.

These changes were not always greeted with enthusiasm and in the post-war period several place-names were changed back to the original, e.g. Marburg.

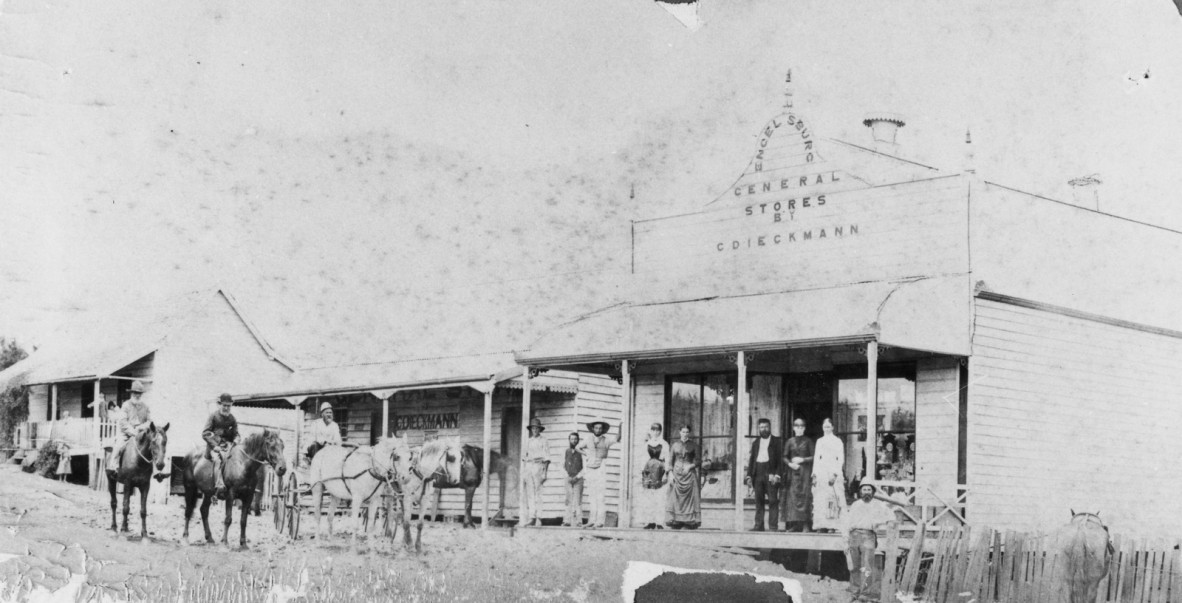

Carl Dieckmann's general store at Engelsburg, now known as Kalbar

John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Negative no. 144170

https://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/101712

Discrimination against German-born residents

The Federal War Precautions Act 1914 and the Aliens Restriction Order 1915 were enacted with a view to limiting opportunities for anyone to aid the enemy.

Anyone deemed to have enemy connections was required to register as an ‘enemy alien’ with their local police. Their movements were monitored and controlled. Many were interned in internment camps across Australia even though they may have been Australian born or had been naturalised.

Anti-German sentiment resulted in significant social changes. German music and culture were banned and Lutheran schools and churches closed.

War propaganda posters demonised the German community and as the news from the Front worsened attitudes to the “enemy in our midst” hardened.

Many formerly well-respected Queensland pioneers of German origin found themselves the objects of suspicion, hatred, and discrimination. Germans lost jobs and their businesses were destroyed.

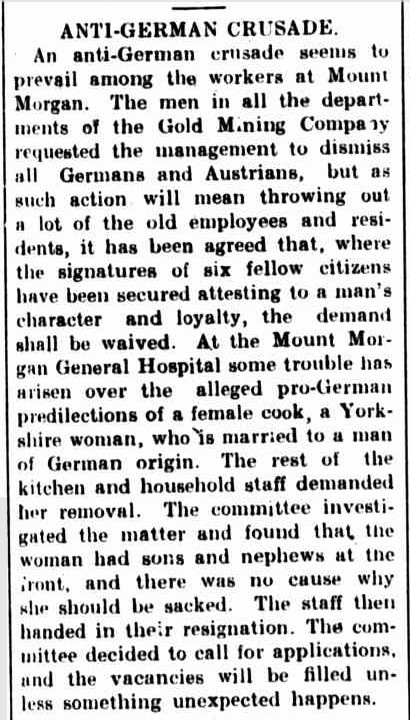

Workers petitioned employers to dismiss co-workers of German or Austrian ancestry beside whom they might have worked for years. The jealousy of a neighbour or co-worker could potentially have a disastrous impact on a family with German connections.

"Anti-German Crusade", Darling Downs Gazette, 27 August 1915, page 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article188217665

An example of this is the story of the German-born Queenslander Ernst Oskar Queitzsch, written by Gwen Price, Tablelands Regional Council Libraries, guest blogger for the John Oxley Library blog.

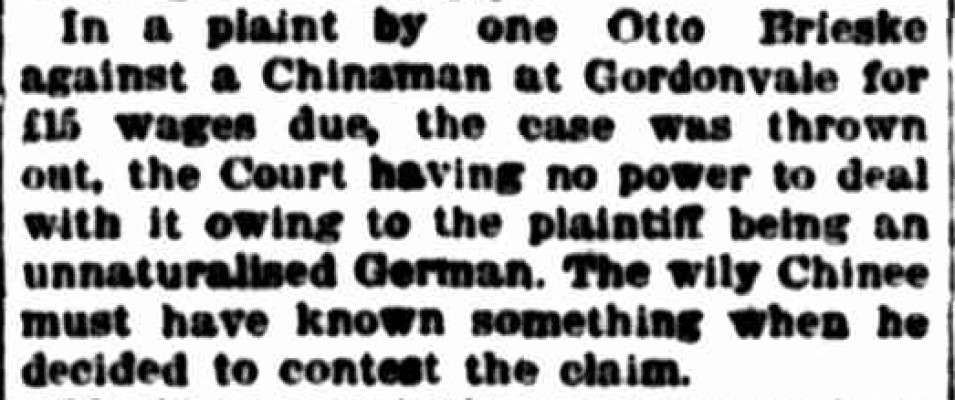

Many German-born Queenslanders, having arrived in Queensland as small children and considering themselves Australian, had not thought it necessary to become naturalized. Now, suddenly, they found themselves without the protection of the law.

Otto Briske/Brieske, a German-born Queensland miner, had married his English-born wife Charlotte Mary Hall in Queensland in 1905. In 1915, while working to support his wife and their five children (all under the age of ten), Otto found himself in a situation where he had to sue his employer for non-payment of wages.

Northern Miner (Charters Towers), 8 May 1915, page 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article79084120

This was not an isolated case and unscrupulous employers often took advantage of unnaturalised German Queenslanders in this way. Otto Briske died in 1928 and is buried with his wife, who outlived him by 45 years, at Babinda Cemetery.

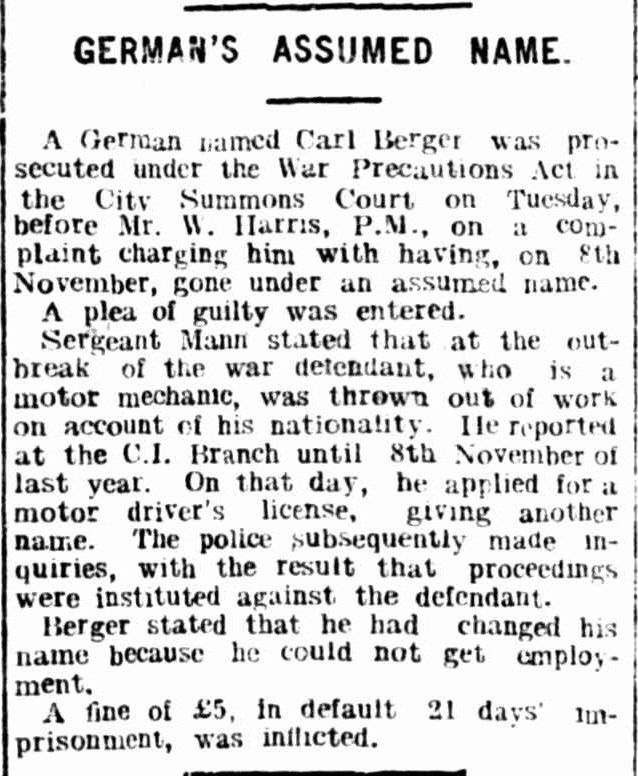

Prior to 1914 German migrants coming to Queensland had often changed or anglicised their names to be more readily assimilated into their new homeland. After the out-break of hostilities there was increased pressure to appear non-German.

Many assumed names that sounded more British or altered the spelling slightly to avoid suspicion that the name was German. ‘Becker’ for example might become ‘Baker’. However, this was illegal, and offenders faced fines or even imprisonment.

Telegraph (Brisbane), 10 May 1917, page 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article189842390

Some families, perhaps hoping to disguise the source of their heavily accented English, claimed to be from a neutral country not involved in the hostilities. Even today some family history researchers can be surprised to find that their ancestors were in fact not Dutch but German.

Family research: a few pointers

- While it is important to search widely and include variants of both personal and family names, it is equally important to check different sources to ensure the variant name you find actually relates to your family. Otto Briske/Brieske (d.1928) is not the same man as Otto Briskey (d.1959) who was naturalised in Queensland in 1901.

- Names of places found in family documents may have been changed. Consult historical maps, directories, and official lists of place-name changes.

- Documents relating to internment of enemy aliens for the years between 1914 and 1918 are held at National Archives of Australia.

- Surviving police records of enemy alien registrations In Queensland are to be found at Queensland State Archives under the name of the specific police division.

More information

- Family History Month - /familyhistorymonth

- Family History - /research-collections/family-history

- Library membership - /get-involved/become-member

- Ask Us - /plan-my-visit/services/ask-us

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.