Siganto Foundation Fellow, Jan Davis reports on her research to date in John Oxley Library at State Library of Queensland.

It is early days and I’m in the research phase of One thing becomes another, my three-stage project to examine diaries and farm records from the John Oxley collection and transfigure them as artist’s books.

Everything is new, exciting. A staff card to hang around my neck is a pretty neat thing and being able to enter the library well before the crowd that gathers for the 10am public opening is a genuine privilege. I’m honoured when SLQ hosts a morning tea to welcome my companion Fellow Douglas Spowart and I, introduce us to Marie Siganto and give us the opportunity to discuss some of our artist’s books that are already held in the collection. I’m eager to learn the ropes about working with original materials and there’s plenty of people to answer my questions. I’m naively delighted when documents that I request are duly delivered to my ‘staff shelf’ without question.

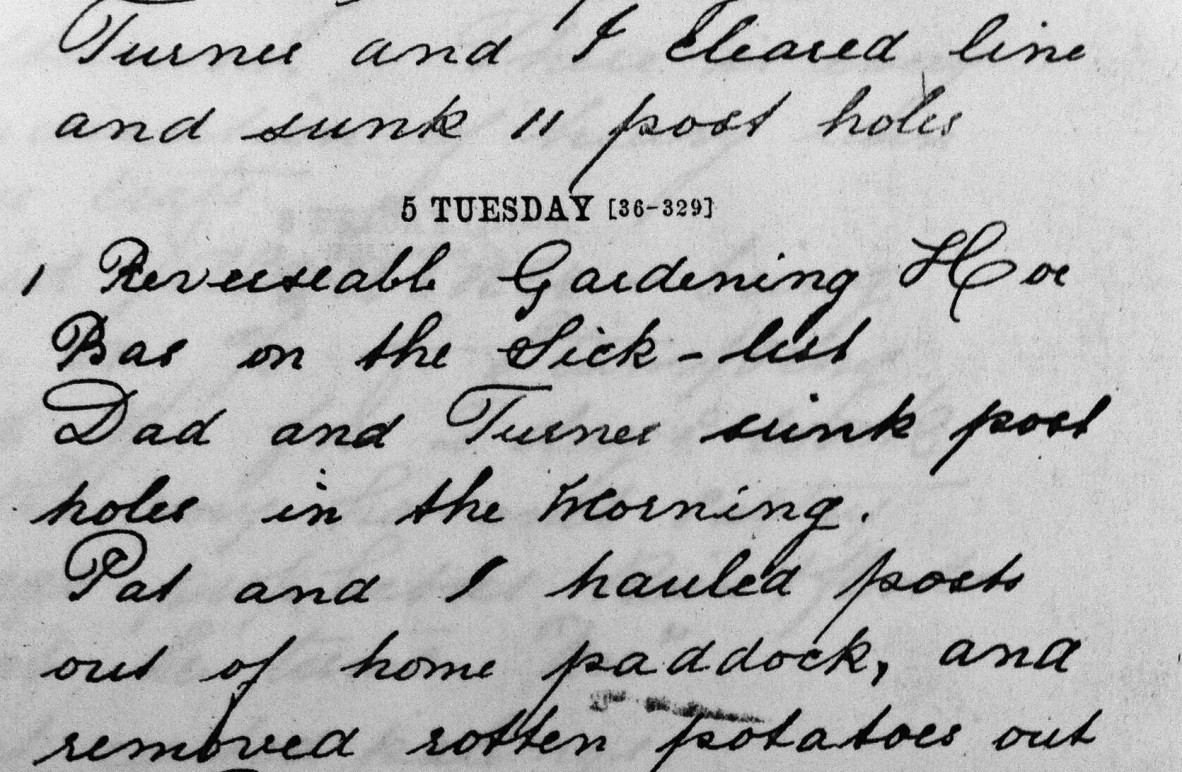

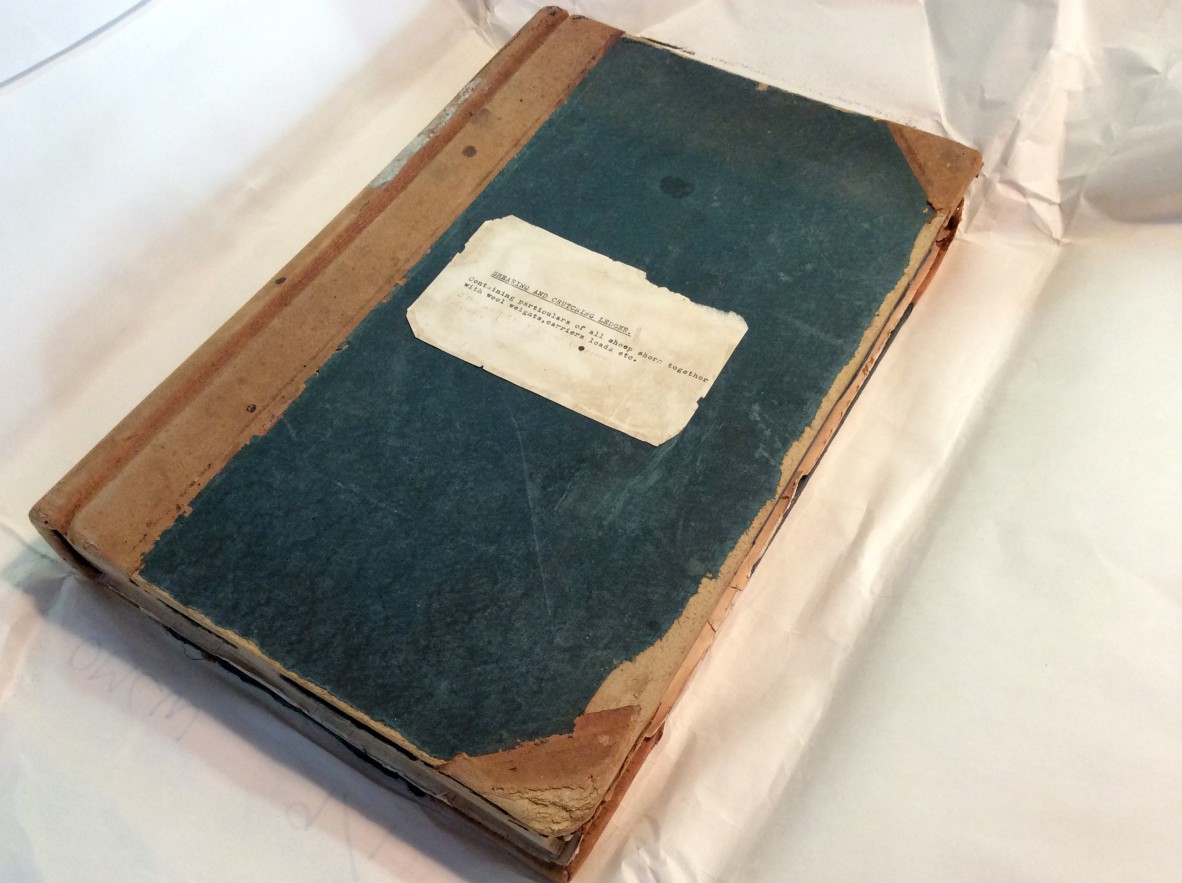

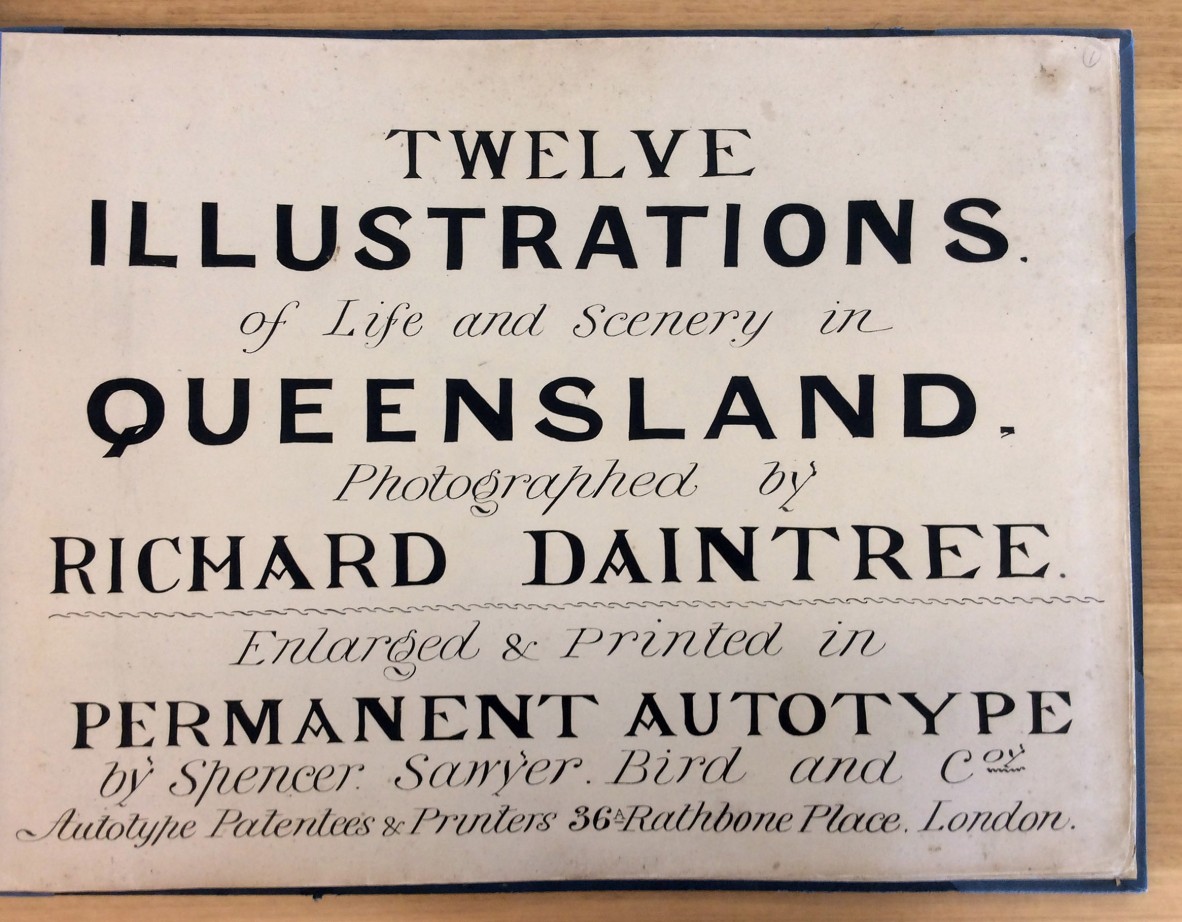

I’m in search of rural toil as I carefully unwrap fragile papers bearing the hand of long-gone gardeners and station book-keepers. I read with equal interest the Talgai Station garden book, the shearing records for Lansdowne Station and the lists of horses kept on Glengallan Station amongst many other documents. In places, I struggle to decipher the 19th century handwriting whilst marveling at the beauty of line resulting from a nib pen. I look at dozens and dozens of photographs by Richard Daintree (1832 - 1878) and William Boag (d.1878) that record some of the working life in Queensland. I scrutinise those photographs looking for clues, imagining the lives of the men and woman depicted.

I’m conscious that I’m bringing the methods of an artist to this project rather than those of an historian who would more commonly be leafing through these pages. I’m using these material records that were made unselfconsciously at the time to serve the purpose of the time, whether to record breeding details, to recall what was planted where and when, or to determine what each shearer should be paid, to inspire my bookmaking practice. I pore over small details because I’m not sure exactly what I’m looking for. The way the ink lies on paper, the way the pages are bound, the manner in which papers have aged, been folded or torn are all potential leads which will guide my subsequent bookmaking as much as the details of the labour contained in the diaries.

The more I read, the more I understand the complexities of my project. The labour by the men and women of Queensland was not always done willingly or with due recompense, and of course, was only possible when the land had been secured at terrible cost for that purpose. So my examination of original material has proceeded in tandem with reading on the history of land settlement and indigenous dispossession, of migration and of race relations in Queensland. And the importance of labour: Queensland was, after all, the birthplace of the Labor Party.

After weeks in the library I’m so infused with images of landscapes and labourers of 19th century Queensland that I can barely find my way home to Northern New South Wales along the four-lane M1, so obliterated are the traces and landmarks of lives recently lived in my imagination in Logan, Beenleigh and Pimpana. Those places again become the names on the green freeway exit signs along the largely undifferentiated outer suburbs of the modern city.

I’m inspired, hoping by the final stage of my project to be able to deliver a new perspective on the records of sweat and toil which now lie snugly in white envelopes, in grey boxes in the beautiful SLQ.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.