Dundalli: Aboriginal resistance hero

By Tania Schafer and Troy Keith, Queensland Memory | 9 July 2021

Cultural Care statement (disclaimer)

Users are advised that this Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander material may contain culturally sensitive imagery and descriptions which may not normally be used in certain public or community contexts. Annotation and terminology which reflects the creator's attitude or that of the era in which the item was created may be considered inappropriate today. This material may also contain images, voices or names of deceased persons.

.

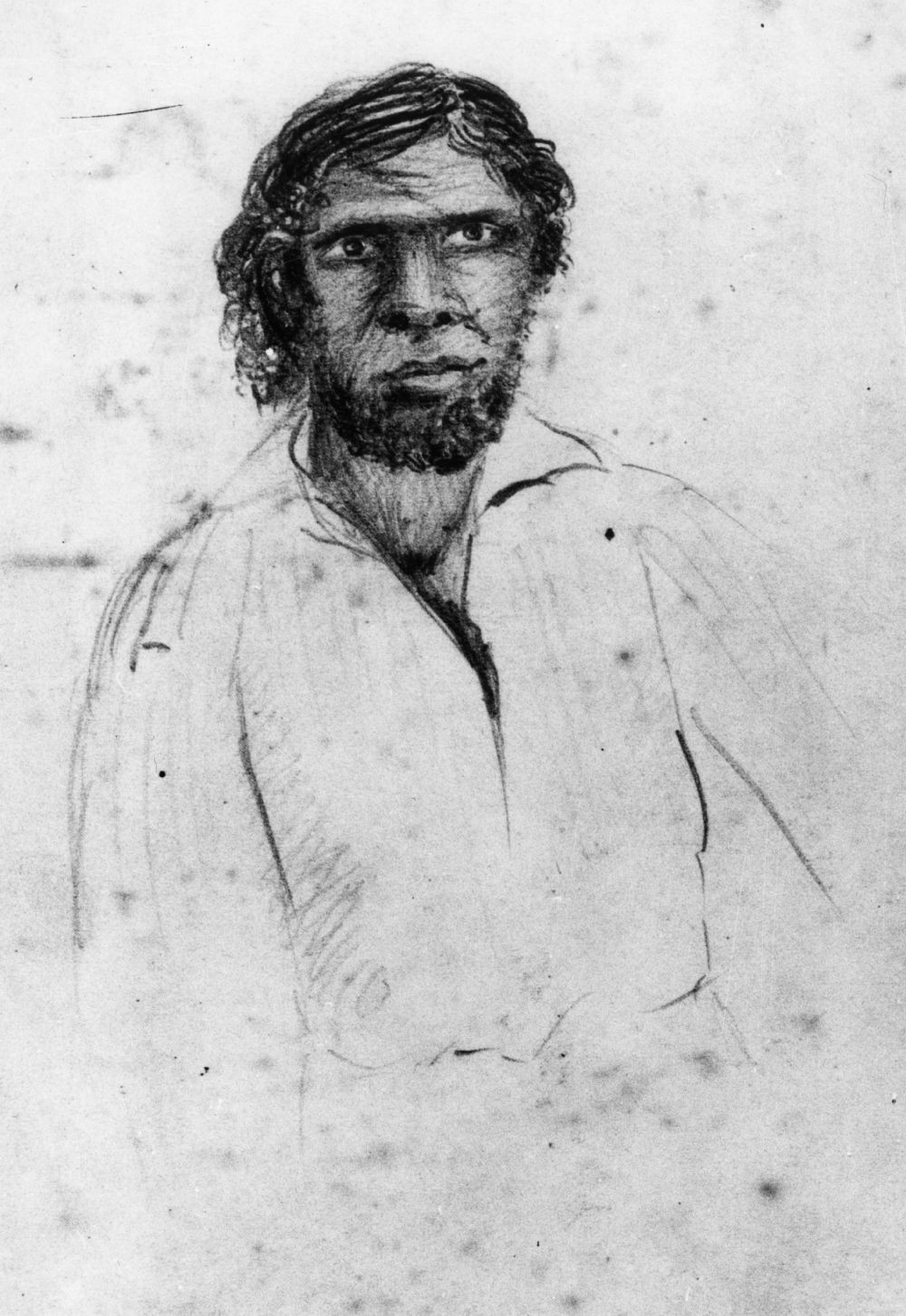

Sketch of Aboriginal Australian Dundalli. Sketch of Dundalli made by Silvester Diggles, 5 December, 1854. Negative number 11307, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

This blog article is a summary of two articles, Dundalli (1820–1855) by Libby Connors and Aboriginal Heroes: Dundalli a “Turrwan” an Aboriginal Leader 1842-1854' by Dr Dale Kerwin. Links to both articles in the Bibliography. It's advised that you view these articles to gain the true history of this interesting man.

Dundalli was a Turrwan (Yuggara word for great man/leader) who was educated in Aboriginal law. (Kerwin 2007: pg 9). He originally belonged to the Bunya group, but for years had been associated with the groups on the coast, over whom he possessed great influence. (J. J. Knight; 1895: pg 336)

Dundalli was chosen as a Turrwan to conduct restorative justice for the shooting and poisoning of Aboriginal people by settlers in colonial Brisbane. For over 10 years starting from 1843, Dundalli attacked settlers, conducted robbery causing serious bodily harm and killed livestock. Aboriginal people saw him as a resistance leader, but the new European settlers saw him as a criminal and murderer. However, Dundalli was only fulfilling his role as a leader within a warrior society ‘warfare is that of reciprocity: if a harm has been done to an individual or a group…they must repay…by an injury that at least equals the one they have suffered’ (Mulvaney 1989: pg3). Encounters in place, outsiders and Aboriginal Australians 1606-1985 by Derek John Mulvaney (available as an eBook on State Library's OneSearch Catalogue) sums up the settler violence and Aboriginal retaliations as a "suffocation of conscience" that lead to a "history of indifference". Mulvaney explains:

In 1854 Dundalli was arrested and sent to trial for: robbing the station of German missionary Rev J.G Haussmann in 1845; the murder of station owner Andrew Gregor and his servant Mary Shannon in 1846; the murder of sawyers Boller and Waller in 1847; the murder of fisherman Charles Gray near Bribie Island; and for the murder of shepherd Michael Halloran. He was found guilty of two counts of murder and one of robbery with violence and hanged in 1855, the last official public execution in Queensland.

The hanging took place at the Queen Street Gaol, where the present day General Post Office now stands in Brisbane, with spectators crowded about Windmill Hill. A large crowd of people both Aboriginals and European settlers attended the execution. As Dundalli climbed up the ladder to the platform of the gallows he called out to his fellow Aboriginals to continue the fight and to avenge his death. He shouted this in his own language and kept repeating his call until he was hanged. (The Moreton Bay Courier 1855, Petrie 1981: pg 175, Knight 1895: pg 337).

In Queensland, between 1839 and 1859, ‘eleven death sentences were passed, of which nine were for murder, one for carnally knowing a child under 10, and one for bestiality’. Over this period six Aboriginal people were hanged and four convicts, none of these hangings generated as much public interest as Dundalli’s. (McPherson 1989: pg 9).

It's an interesting thought that European justice required the hanging of an Aboriginal judge for performing his duties, while Sir Roger Therry, the Judge who was overseeing the proceedings and the Executioner, Alexander Green, were not put to death for committing the same offence as Dundalli.

This photograph was taken in 1863, 8 years after Dundalli was hung but you can see in the background the old Queen Street Goal which once stood where the current Brisbane Post Office now stands.

Crowd gathered for the government blanket distribution in Queen Street, Brisbane in 1863. Negative number 7773, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Bibliography

Most of these books are available to read as eBooks through State Library's OneSearch catalogue .

- Encounters in Place, Outsiders and Aboriginal Australians 1606-1985 by D. J. Mulvaney (Derek John), 1925-2016 ; St. Lucia, Qld : University of Queensland Press ; 1989

- Tom Petrie's reminiscences of early Queensland (dating from 1837) / recorded by his daughter [Constance Campbell Petrie]. Thomas Petrie 1831-1910. ; Constance Campbell Petrie 1873-1926. ; Whitefish, MT : Kessinger ; 2009.

- In the early days : history and incident of pioneer Queensland : with dictionary of dates in chronological order by J. J. Knight (John James) ; Brisbane, Qld. : Sapsford & Co. ; 1895

- The Supreme Court of Queensland, 1859-1960: History, Jurisdiction, Procedure by B. H. McPherson (Bruce Harvey) ; Sydney : Butterworths ; 1989.

Other interesting sources of information on Dundalli:

- Working Paper Number 1: Aboriginal Heroes: Dundalli a ‘Turrwan’ an Aboriginal Leader 1842-1854 by Dr Dale Kerwin; Mt Gravatt: Griffith Institute for Educational Research, Griffith University Press; 2007.

- Aboriginal heroes: episodes in the colonial landscape by Dale Kerwin; Queensland Historical Atlas: Histories, cultures, landscapes; 2010

- Warrior : a legendary leader's dramatic life and violent death on the colonial frontier by Libby Connors 1960- ; Crows Nest, N.S.W. Allen & Unwin ; 2015

- Dundalli (1820–1855) by Libby Connors; Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2005

Newspaper articles about Dundalli on Trove:

- Andrew Gregor and his servant Mary Shannon are killed in an attack by Aborigines, Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane), 24 October 1846, p 2

- report on the attack on three sawyers during which William Boller was killed; Dundalli was identified as one of the attackers, Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane), 18 September 1847, pp 2-3

- Dundalli is captured by police, Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane), 27 May 1854, p 2, column 2

- The charges against Dundalli, Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane), 3 June 1854, p 2

- Dundalli is found guilty of the wilful murders of William Boller in 1847 and Andrew Gregor in 1846, Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane), 25 November 1854, p 2, column 2

- Ordered to be executed on 5 January 1855, Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane), 19 December 1854, p 1

- Execution, Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane), 6 January 1855, p 2

- His last words, Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane), 13 January 1855, p 2

This material contains Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander content, and has been made available in accordance with State Library of Queensland’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collections Commitments.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.