The Desert Column : the WW1 diaries of Ion Idriess

By Simon Miller, Library Technician, State Library of Queensland | 4 August 2014

Ion 'Jack' Idriess is an important, prolific and extremely popular Australian author who spent many years in North Queensland and the Torres Strait and whose work provides important insights into life in those sparsely populated areas in the early decades of the Twentieth Century. I have earlier looked at Idriess' work on North Queensland in the John Oxley Library blog in Tin and sandalwood and his contribution to the discussion of developing northern Australia in The Empty North. The State Library holds an extensive collection of Idriess' works which can be accessed through the One Search Catalog

Idriess was at Cape Melville, 200 miles north of Cooktown, on Cape York Peninsula prospecting when news of the war reached him via the captain of a passing lugger. He was determined to join up at once and since the captain was heading in the wrong direction Jack set out to get to Cooktown on foot. His efforts were thwarted by a deep river full of crocodiles and sharks and he had to go back to Cape Melville to await the return of the lugger to get a ride to Cooktown only to discover there was no recruiting station there. He stowed away on a boat to Cairns and then on another to get to Townsville before he could have a chance of enlisting.

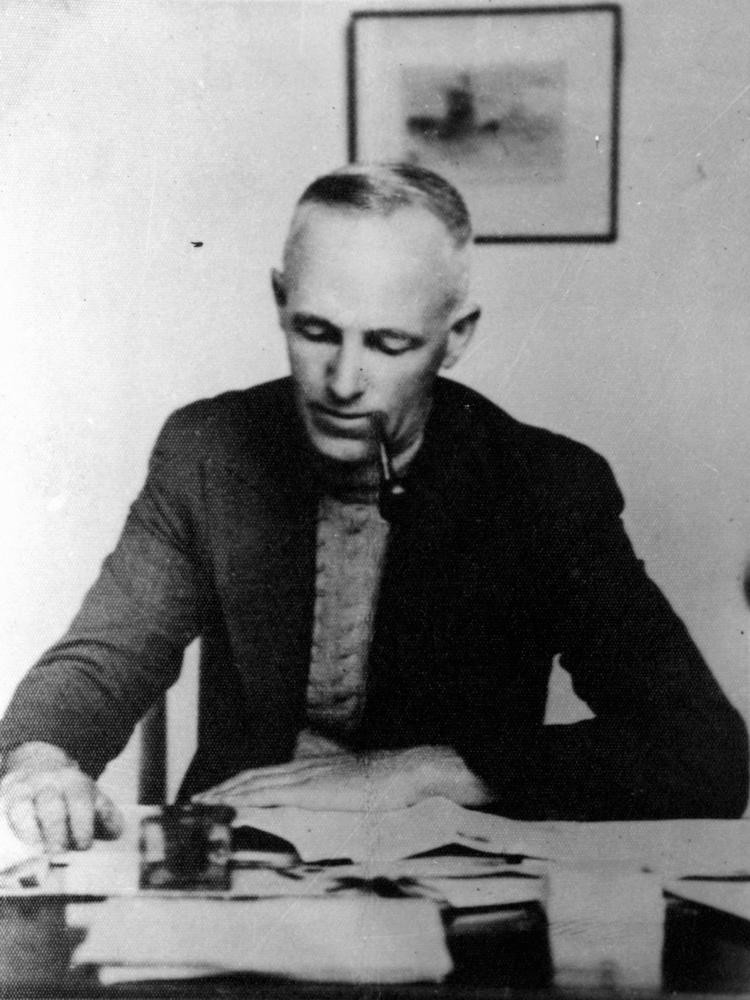

Trooper Idriess kept a diary throughout his war service and these diaries would later form the basis of his book The Desert Column. It wasn't until 1929 when a diagnosis of cancer forced him to give up his wandering and concentrate on writing that Idriess retrieved his war diaries from a haversack stored at his sister's house in Grafton and set about turning them into what became The Desert Column. It then wasn't until 1932, after the success of his most popular work, Flynn of the Inland, that the book was published. Jack had wisely asked General Harry Chauvel, the former commander of the Desert Mounted Corps to write a foreword to the book. This endorsement by a highly respected General was used by Jack in his campaign to get the book published.

Several books have been written by officers and war-correspondents but in this the campaign is viewed entirely from the private soldier's point of view. It is of absorbing interest to a leader and should be to the general public. At the same time there is an accuracy in the descriptions of operations which could only be provided by a singularly observant man. Idriess was, I think, above the average in this respect though I must say that the Australian Light Horseman was generally very quick in summing up a situation for himself. No doubt his early training in the wide spaces of the Australian bush had developed to an extraordinary degree his individuality, self-reliance and power of observation, and the particularly mobile style of fighting he was called upon to take part in suited him and brought out his special qualities far more than any trench warfare would have done.

The first part of The Desert Column deals with the action at Gallipoli. It opens with an entry : Transport Lutzow, Cape Hellas, Dardanelles, May 18th, 1915

Evening - An elusive vista of hills behind the dim outline of ships, a faint boom-oom-oom, then, like bursting stars, the shells struck a hillside here, there ! over there ! here again ! everywhere !

Intense excitement amongst the 2nd Light Horse Brigade as our transport glided to anchorage. What a roar of voices as and extra vivid flame crashed on a black hill! Then night settled down and the bombardment ceased. At midnight a furious outburst of rifle and machine-gun fire broke forth from the land ; but most of us slept, quite soundly.

Idriess brings a uniquely Australian mix of gritty realism and humour to his Gallipoli story.

May 29th - It is a cold, grey dawn. Death is bursting all around us now, but plenty of the boys are crawling out and lighting their little fires. A long, tanned bushman is kneeling down, blowing carefully into flame a few dry sticks ; a smoke-cloud from an exploded shrapnel-shell is drifting into the air above him. A counter-jumper on the gully opposite is bemoaning the swine who pinched his scanty supply of wood, and invites the unknown lousy thief to come out and fight. And one fair-haired chap is combing his nice wavy hair with a dirty old broken comb.

... They are calling out for stretcher-bearers now. I don't know how many are hurt. The Indian stretcher-bearers are busy too ... What miraculous escapes! A shell has just burst in front of me ; ten feet below two infantry chaps are cooking their breakfast. They were splattered with smoke and earth but refuse to leave their cooking. As I write, another shell has burst beneath them, but still the obstinate goats won't budge. Another has come and this time they grabbed their pots and ran. We all laughed. By Ceasar! it is about time they did run. A fourth shell has come and where their fireplace was is now a cloud of smoke, ashes, earth, and fragments of shell. Shells are bursting amongst us all over the hill and up and down the tiny gully.

Idriess was wounded twice at Gallipoli. The first was a superficial shrapnel wound to the knee which became infected and required evacuation to a hospital for treatment. Superficial wounds commonly lead to serious infections as wounds were only dressed and no other treatment was available. The second more serious wound was received during a hellish spell in the front line trenches at Lone Pine. These trenches, only a few metres from the Turkish trenches were dangerous, uncomfortable and horrific, with the bodies of the dead incorporated in the walls of the trenches and the whole place thick with flies and maggots. Jack's troop was just being relieved when a Turkish bomb landed amongst them.

At long last the relief came stumbling in ; we could not see them, we could hear them down there in the the dark. At last they groped along the trench and clawed up over us, no man stepping down from the firing-possy until a new man had taken his place. We survivors of the old relief crouched down there in the trench. It was an awful feeling, waiting there, staring upward expecting hurtling bombs or mad Turks jabbing down at us any moment. At last the man behind me whispered : "File off!" I stuttered the word on, and we pressed man against man, shivering in the hope that soon we would be under some sort of cover. But in that awful slowness of moving we saw hissing sparks flying over the parapet - a choking cry, "Bomb! Bomb! Christ!" I tried to jump back but the men pressed behind were new hands and did not know what to do. Poor old King was in front of me. He jumped forward, but the men ahead crouched in the blocked trench. King was on a slight incline and as the hissing thing thudded it rolled horribly towards him. I thought the end of all things had come - I threw my overcoat over it, clenched my arms across face and stomach and pressed desperately back against the men behind. Then all was a suffocation of deathly fumes - I was on my back, quite distinctly hearing the clash of bayonets as rifles thumped across me. Then followed a strange, dull silence, ears ringing like mad. King called out : "I'm wounded, boys." I called out, "So am I, Kingey," and struggled up.

Idriess was evacuated again. King died of his wounds on the hospital ship. "King was always game. He was a gentlemanly sort of chap, too, and he died game." Idreiss did not return to Gallipoli. He spent some months recuperating at Alexandria and missed the evacuation. He rejoined his regiment on January 5th 1916 in Cairo as the Light Horse regiments turned to a different kind of warfare in the deserts of Egypt and Palestine. Soon after he makes some remarks about their officers.

February 13th - The Old Bird is back, happy as a lark. All the old hands are glad to see him. The whole brigade is lucky with its officers. Some are pigs ; but I suppose they can't help that. The big majority however are well liked. All the brigade likes the Old Brig. By the way, he can sling a boomerang better than any white man I know. Then the 5th like Colonel Wilson. He fined me five shillings yesterday, though, for clearing out on Sunday without leave.

The Light Horse were ideally suited to the desert warfare in North Africa. Their chief objective was to protect the Suez Canal and they were successful in pushing back the formidable Turkish army backed by Austrian artillery and engineers. In July of 1916 Idriess was chosen to be part of a dangerous reconnaissance mission to spy on a big Turkish camp. One morning a party consisting of Lieutenant Stanfield, Seargent Paul and four troopers, including Idreiss and two British artillery officers who had been sent out to scout out artillery positions set out for their outpost on a hill overlooking the Turkish camp and narrowly escaped ambush.

Bedouins crouched amongst the bushes. All down the left side of the valley were waiting men. The sight of all those waiting Turks took our breath away. Three big chaps crouched up trying to level their rifles through the bushes to get a clear shot at our heads. I jerked up my rifle, but at that very moment rising opposite us from the other side of the razor-back only twenty feet away appeared the black cloth elbow, then the rifle muzzle, and then, very slowly and cautiously the head of a Bedouin. I bit my lip, in taking aim, to keep steady, then crack, crack, crack, three bullets in a second and the Bedouin clenched out his arms and bit with his mouth in the sand. "On your horses, boys ; quick!" shouted Stanfield.

One jump and we were down the razor-back. "Steady, boys, there's plenty of time," shouted Stanfield ; then immediately each man was in the saddle he dug the spurs in and laughed as his horse leapt away, "Come on, boys, and we'll give these _______ a go for it! Ride like the hammers of hell!" In a bound the four horses were away and in the same breath we could see the sand spurting around the artillery officers and men half-way down the hill, then in one dreadful second my horse stumbled - and fell! My Heavens, he rolled over on top of me - I thought that if I lost my head in the next few seconds I was done. I just heard Stanfield's vanishing shout : "Whose horse is down?" while I snatched at the struggling beast's head as he foundered for a foothold, madly excited. I snatched the ringed bit and held him steady ; he quietened instantly as Sergeant Paul galloped back. My head was buzzing, but steadied like the horse when Paul said quietly : "Steady, lad, there's plenty of time. Mount him again." - I snatched the rein as he floundered up and he pulled me up with him. I dared not raise my eyes to that razor-back. I understood now that everything happened so quickly that the dead Bedouin's mates dare not raise their heads, not knowing what was awaiting them. I swung into the saddle as the first bullets hissed by and in seconds we were galloping through what sounded like a shower of red-hot hail. How our horses raced to rejoin their mates galloping far down the hill! I had one foot in the stirrup, the other stirrup-iron and the feed-bag were doubled up under the side the horse had fallen, but I could feel by the plunging gallop that the neddy was not going to fall again, and that ride was simply grand!

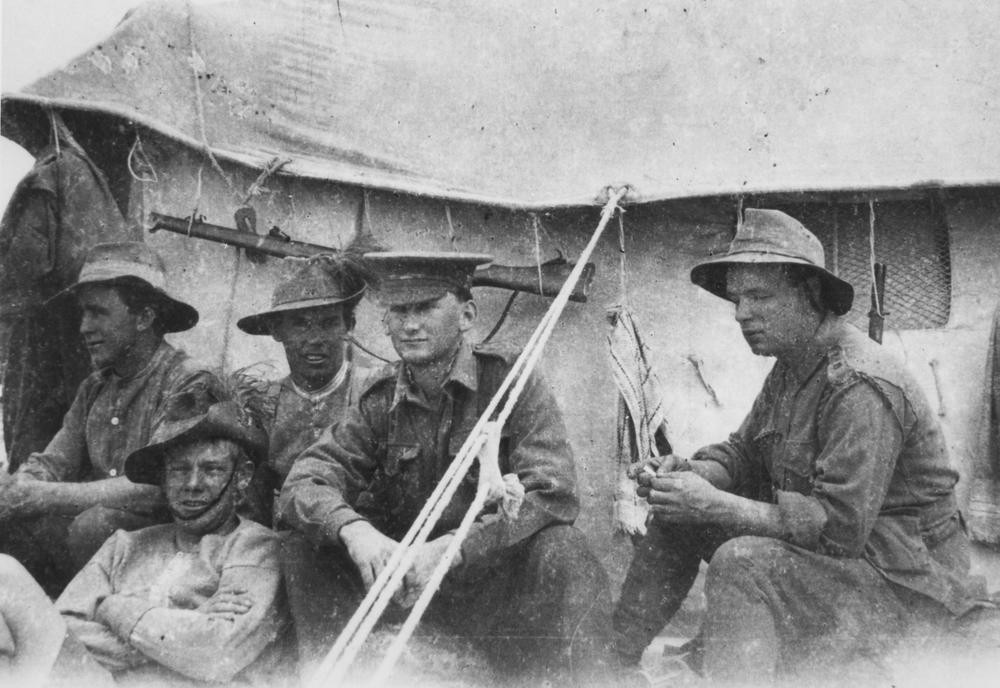

The core of the Australian Light Horse was the four man section, trained to work together and able to act with considerable independence when required. After some heavy fighting during August Jack and the rest of his section, Morry, Stanley and Bert enjoyed a brief respite as they were sent off as a section to make contact with another unit. Having delivered their message they seized the opportunity of being out on their own bearing in mind some goats that they had seen in an oasis on their way out.

Presently, as there was nothing doing for us, we sneaked away, mounted and went for a good long cruise entirely on our own, scouting and then galloping into every oasis we came across. We got no prisoners, only old Bedouin belongings hidden under bushes. We hunted for water-melons and ripe dates. We boiled our quarts in a quiet little oasis and enjoyed our bully-beef and biscuits, but we were hungry. We felt we ought to find something on a day like this. In this particular oasis grew fig-trees but, like everything else in the blooming desert, the figs were poor. That was one of the good days the four of us had together. We were glad to be alive, glad to be in each other's company.

In the afternoon, we rode back for the goats. Silly old Bert let the damned things break loose. He laughed - I swore and galloped after the goats going hell for leather towards the Turkish camp. I chased one for half a mile, then jumped off and fired - blessed if I didn't miss. Feeling like a goat myself I galloped after the fleeing thing again - it was in full sight of El Abd before I could run the horse over it. Stan came galloping up and slung the panting thing across his saddle. We set off lively, expecting a shot every second, but I suppose the Turks were far too busy to bother about two men and a goat.

After a canter, we caught up with Bert and Morry having the devil's own job driving their goats. Our horses plainly did not like the goats, they tried to tread on them. We got the mutton to camp just before sundown, killed two straight away and when the regiment rode in, C Troop had mutton for supper. It was a glorious feast. Bert found that the goat which had given me so much trouble owned a lot of milk, so I held the scraggy beggar while Stan milked her. He squeezed out half a quart and it went grand in the tea. She kicked a bit.

In December 1916 Idriess was seriously ill with malaria. When he recovered from the worst of the fever he went on sick parade to get treatment for the septic sores that continued to plague Jack and most of the men.

I was sitting down waiting my turn, talking to the Red Cross sergeant on the gully-bank when - whee-eee-eezz crash! Instinctively we had thrown ourselves on our faces but the shell exploded too close. I spent awful seconds wondering whether I was hit mortally. A whirlwind of bells was ringing within my head, and I knew that until the bells quietened I would not be able to think clearly at all. The first recognizable feeling was the numbness, with my mind trying to telephone to all parts of the body to find out which were still there and which broken. Then quick as anything I realized I had a good fighting chance though I still felt numb down my back. The bloody hole in the arm and thigh did not matter. Soon I was swathed in bandages. By the rules of the game I should have been blown to pieces but there was not even a bone broken, just a dozen shell splinters.

After an agonizing journey by various ambulances and trains he arrived in Cairo in Christmas Eve. On January 2nd he writes I am to be returned to Australia as unfit for further service. Thank Heaven!

Jack played down the extent of his injuries but they were very serious and he was told he would never walk again. The doctors in Cairo had tried to remove all the pieces of shrapnel but there was a large piece lodged against his spinal column that it was impossible to remove, a souvenir he would carry with him for the rest of his life. There was also a large fragment in his right thigh and numerous other pieces. On being discharged in Sydney, Jack turned to physical culture advocate Reg 'Snowy' Baker. Snowy Baker was a champion athlete in many sports who, being turned down by the military due to a back injury, devoted his energy to fund raising events such as the 1914 Patriotic Carnival in Brisbane. Baker's physical training program restored Idriess to health and fitness.

Simon Miller - Library Technician, State Library of Queensland

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.