The Coming of the Electric Light to Queensland

By Administrator | 28 April 2017

The electric light came to Queensland homes in the 1880s. The collections of the State Library of Queensland are rich in scientific journals, photographs, and many publications that document this wonderful new innovation.

The magic of turning on the light was first displayed in 1882 in Queen Street and people gathered to marvel at bright white light. “There was but one expression – that of unqualified admiration” reported The Brisbane Courier on 13 December 1882. However, it took some years before Brisbane’s city streets were fully lit by the electric light. Gas lighting, although yellow and pale, was cheaper. Some Queensland towns like Croydon in the far north did not have access to electricity until 1980. Richmond, Julia Creek and Boulia gained access to electricity in the 1950s, Boyne Island in 1960 and some pastoral areas are still powered by diesel generators.

Yet some towns and shires with motivated mayors or leading citizens ensured that the magic of the electric light came to their township as early as the 1890s. By 1927, it was reported in a newspaper article that “a town is nowhere without electricity”, whilst congratulating the people of Goondiwindi and St George on voting for the adoption of electric power (Balonne Beacon, 29 September 1927, p. 6). Many Shire Councils asked citizens to vote on whether to spend the large amount of capital to make electricity available in their area. In Charters Towers in 1926, the majority of citizens voted against the City Council’s proposal to borrow 33,000 pounds to install an electric light and power service.

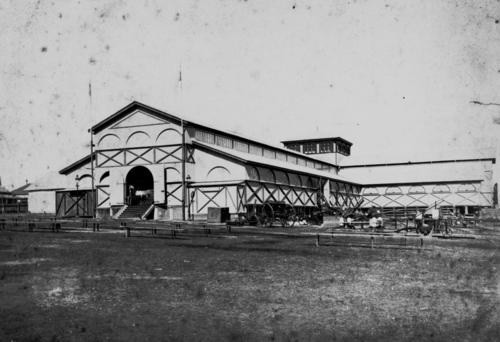

Many Queenslanders were worried about this new technology. In 1890, it was noted that “the dread of fire from the improper insulation of the electric lighting wires is certainly not an illusory one” (The Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette, 29 April 1890, p.4). As late as 1907, Australian newspapers were reporting that “electric lights and electric wires of all sorts poison the air, hurt your lungs and even eat out the lining of your stomach” (The Brisbane Courier, 22 March 1907, p.9). Newspapers throughout Australia were filled with concerns and dread. In Brisbane, this was not helped by the complete destruction of the wooden Exhibition Building on Gregory Terrace in June 1888, which, according to the investigation, may have been linked to the use of electric light in the building to allow it to be used as a night time skating rink.

Brisbane’s first exhibition building, destroyed by fire in June 1888 – electric lighting allowed the building to be used as a roller skating rink at night. State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 183745

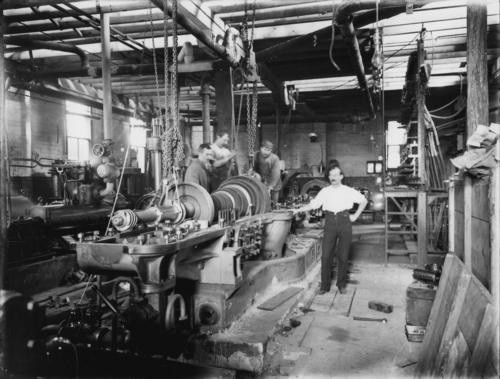

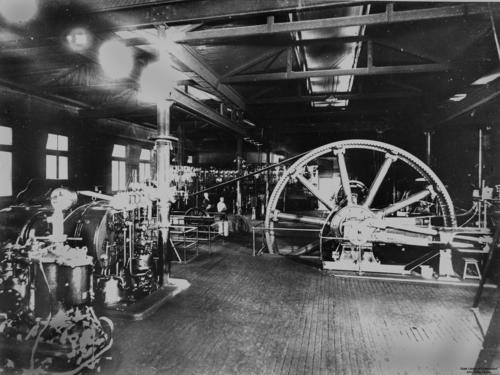

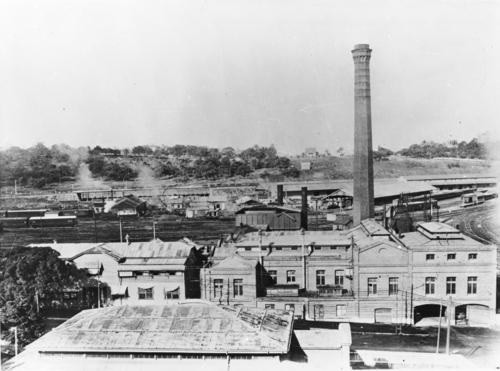

The father of electricity in Queensland was Edward Campbell Barton, Queensland Government Electrical Engineer, who founded the company Barton and White in 1888. A graduate of the Karlsruhe Technical Institute in Germany, Barton had worked for Siemens in Woolwich, London and had worked on the installation of the electric light in Surrey before coming to Australia in 1884. Barton provided much expertise to country towns, mines and sugar plants, and shire councils, including the Brisbane City Council. Queensland’s Government Printing Office, General Post Office and Parliament House all adopted the use of electric lighting prior to 1888. Queensland did not have an Electric Power Act until 1896 and a lack of regulation led to wires being draped all over the city streets and roof tops. In Brisbane, the City Electric Light Company in Brisbane was formed in 1904. However, the introduction of electric trams in 1897 required a dedicated power house to be constructed in Countess Street and the shire of Ithaca obtained permission to provide light to Red Hill and Ithaca area from 1900.

Workers at the Electric Light Co., Brisbane, ca. 1910. State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 39185

Interior of the Countess Street Power House, Brisbane, ca. 1912. State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 22196

An external view of the Countess Street Powerhouse, Brisbane, ca. 1925. State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 22201

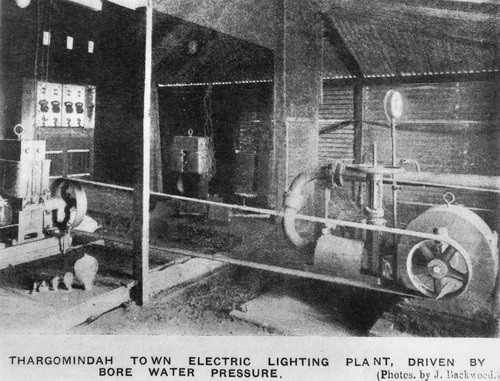

The first electric lighting available outside Brisbane was at Thargomindah. Using hydro power from an artesian bore, electricity was generated using a locally made water wheel. At first, only 15 consumers were supplied but by 1898, it was reported that there were 60 lamps powered by the first hydro-electric plant in Australia. The town was widely praised in the media for its innovation.

Electric lighting plant, driven by bore water pressure in Thargomindah, Queensland, 1904. State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 9605

Power station for Australia's first hydro-electric scheme at Thargomindah, Queensland, ca. 1898. State Library of Queensland, Negative number: 39213

Other Queensland towns that adopted electric lighting as early as possible were Rockhampton (1898), Toowoomba (1905), Warwick (1912) and Ayr (1914). Each Queensland town that adopted the electric light chose their own solution and hence by 1936, a Royal Commission was called to investigate the standardisation of power in Queensland. Western towns and shires were generally running on Direct Current power (D.C.), while coastal cities had adopted the more versatile Alternating Current (A.C.), which could be sent longer distances without a voltage drop.

Mining towns and towns in the sugar areas often had their power supplied by the sugar mill or mine. Nambour is one example of this, where the sugar mill provided the power, when surplus to its own needs, to the township. This included power supply to the hospital, which had electricity for a few hours in the morning and night and had to exist with Kerosene lamps for the rest of the day. As part of the Royal Commission, many “make-do” power generation arrangements were uncovered. The Star Picture House in Nambour was discovered to be illegally supplying some of its neighbouring businesses with power. Most Brisbane suburban areas and rural areas in South East Queensland were supplied in the 1920’s with power. After World War Two, the State Electricity Commission, convened as an outcome of the Royal Commission, began a process of aiding small towns in Queensland to gain access to electricity.

The question of whether to have poles above the ground, or underground cable caused much discussion. Erecting poles for electric light and power, Atherton ca. 1937. State Library of Queensland, Image number: 6670-0001-0046

Gradually, the magic of the electric light came to Queensland as did the electric cooking range, electric coppers, irons and vacuum cleaners, refrigerators and radios, which enabled the development of the modern home throughout the state.

More information:

A history of the electricity supply industry in Queensland / by Malcolm I. Thomis http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/SLQ:SLQ_PCI_EBSCO:slq_alma21126662350002061

Researching the history of electricity in the State Library collections / by Dr Henry Reese https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/blog/researching-history-electricity-state-library-collections

Images from John Oxley Library Original Materials collection 28723 Electricity and Hydro-electricity Glass Plate Negatives 1902-1904 http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/SLQ:SLQ_PCI_EBSCO:slq_alma21148611630002061

Ask us: /services/ask-us

One Search: http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au

Christina Ealing-Godbold

Senior Librarian, Information Services

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.