From Brisbane trainee nurse to U.S. war bride: the diary of Elvie Geissmann

By JOL Admin | 8 March 2019

Guest blogger: Debbie Terranova – QANZAC100 Fellow.

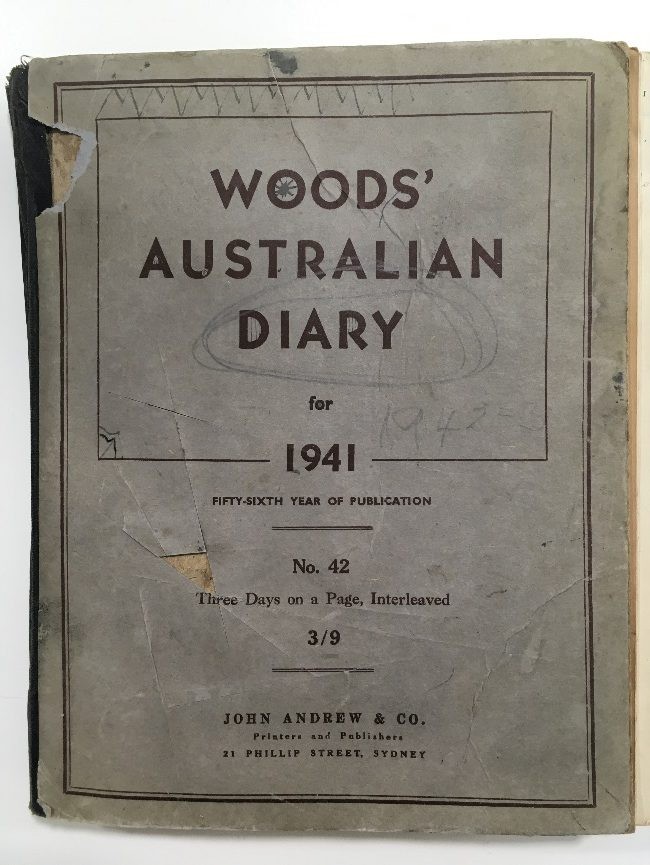

In January 1941, the Brisbane General Hospital accepted twenty-year-old Elfriede (Elvie) Geissmann as a trainee nurse and she moved into the nurses’ quarters1. There she began a personal diary in which she recorded the trials, hopes, and despairs of a young “British born”2 woman during World War Two.

1941 diary of Elfriede (Elvie) Geissmann. State Library of Queensland collection. Image courtesy Debbie Terranova

Until then, Elvie’s upbringing had been relatively carefree. She was surrounded by a large extended family which operated sawmills and a guest house on pristine Tamborine Mountain to the south-east of Brisbane. Tennis, picnics, horse riding, swimming in the creek, playing the piano featured large in her life on the mountain. The year before, Macolm, her then eighteen-year-old brother who was a pre-med student at Queensland University, had joined the R.A.A.F.3 and her “first serious boyfriend”, Desmond, had enlisted in the A.I.F. Both had already been shipped off to fight on the other side of the world.

The diary entry on Monday 6 January 1941 announced, “I am a nurse now and everything has been O.K. so far. Everyone is very friendly and jolly. We have to be in bed by 10.30pm and have to report at 7.50am tomorrow … I will write home, and to Desmond and Macolm tonight.”

Elvie’s first patient experience in Wards 8-9 (ear, nose and throat) was somewhat confronting. On 11 January she wrote, “I do not think I will ever really like nursing, not at this rate any way … one old man flabbergasted me by asking for a bottle. I did not know what he meant but shrewdly guessed, so I rushed up to another nurse and told her. I hope she fixed him up.”

Entrance to nurses' quarters at Brisbane General Hospital in Herston, Queensland, 1925. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image 161497

Desmond was constantly on her mind and she pined for letters that arrived with frustrating irregularity. After seeing 40,000 Horsemen at the “pictures"4, she wrote, “It is a marvellous picture but I hated it as I could not get it off my mind that Desmond is in similar hell.”

Her trainee nurse wages were also a disappointment: “24/85 for the fortnight”. In vain she attempted to rein in spending. Most weeks she agonised over a debt to the T.C. Beirne department store in the Valley6. Yet, despite frequent reminder letters to repay, she would crumble to temptation and purchase a new hat, or gloves, or fabric to make a dress to wear to the pictures or a show.

“I don’t know how I am going to manage on two weeks’ pay if I buy my handbag, which I am determined to do. I will have to buy another skein of wool to finish my jumper.” Two days later “I bought my handbag - 16/117".

Shoppers purchasing rationed goods in T.C. Beirne's store in Brisbane during World War II. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image 112044

When she accidentally broke her watch - a necessity for a nurse - she wrote, “I felt a fool in Woolworths for I said I would have one of the 12/118 watches and then I found I had not the money”. Her father helped her buy a better one from Wallace Bishop, the jeweller.

From the outset of her training, she struggled with the discipline demanded by her superiors. “Today was rotten. We got into trouble right and left. We were asked whether we liked nursing and only two of us said ‘no’. I was one poor fool so I got a piece of fireworks.”

The work itself was challenging, for the trainees were given the dirtiest and most menial of tasks. “It was operation day. I had a simply huge pile of bloody linen (very, very bloody) to clean up.” To lighten the mood, she and another young nurse walked to the Valley to buy lunch. “Two pies, a pineapple, two cream puffs … and 6 chocolates.”

Brisbane General Hospital, Nurses lecture room, 1946. Qld State Archives, Digital Image ID 2877

With the preliminary exams over, Elvie was rostered on to the wards. Shifts were from 6am to 4pm and the summer was “beastly hot”. She complained of tiredness, sore feet, dingy accommodation, and aching legs. “I am hating this life more than ever.”

On 25 March, a fleet of American navy vessels arrived in Brisbane on a goodwill visit. During a parade through the city streets, guards had a tough time holding back multitudes of enthusiastic women. Next day Elvie wrote, “Several nurses went out with the sailors and are doing the same on other nights. I hope they enjoy themselves as I doubt whether I would.”

One day later she wrote, “Jensen9 and I departed at 4 - went to the wharves. We had a glorious time.” Through a porthole they conversed with a Navy medical orderly for more than an hour and came away with souvenirs: “an autographed tongue depressor” and “a nickel and a dime”.

Happy crowd in Queen Street, celebrating the arrival of American Forces, Brisbane, 1941. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. Image 202863.

In April, Elvie was assigned to Wattlebrae, the infectious diseases unit “where all the naughty nurses go.” In 1941, “most of the patients are children with whooping cough but there are four scabies, one diphtheria, one syphilis, one mumps.” In Wattlebrae, some of the patients caused her trouble. “One of the ‘gonny10’ patients has been inviting the nurses to her place and we know she is looking for recruits for her ‘House of Infamy’.” Others, Elvie found totally repulsive. “We had a dreadful case come in tonight - syphilitic and drunk as a fish. A really choice specimen of humanity.”

On 12 April there was “a rumour that Australians have been captured in Libya but the report is unconfirmed from London. I hope it is not true but I suppose it is. I never know whether the papers are making the best of things or whether their optimistic outlook may be relied on.”

The war seemed to be drawing closer to Australian shores and the diary entries were showing her mounting concern. “The war news is very serious and we might be fighting Japan before long.” As the likelihood of invasion grew, security measures were tightened and there were drills and blackouts. “Tonight the bomber from Melbourne was circling the showgrounds11" in the searchlight beam and looked very imposing. Nevertheless I can’t see what use one searchlight would be against a couple of hundred enemy machines.”

Locket showing Elvie Geissmann and Roy Bridges, a U.S. serviceman whom she nursed and later married. State Library of Queensland collection. Image courtesy Debbie Terranova

With a move to a male ward and assigned to continuous night duty, Nurse Geissmann encountered her most confronting situation yet. One of the patients had developed a crush on her and would not take ‘no’ for an answer. On 17 August, “Tommy had an operation and needed much sympathy last night. Goodness me, he is a trial to me. He says he is in love and Salisbury seems to think he means it. I think I would be a fool to fall for his charms knowing all I do know about him.”

On 22 August Tommy became physically demonstrative but she received no support at all from the workplace. “I just don’t know how to keep him off. I have been very cold lately and he has been peeved but it is wearing off.” A few days later, “Last night Tommy kissed me again so now he has cooked his goose. This behaviour is disgusting and sordid … I have never felt so silly and cheap in my life. Salisbury thinks it is funny but my sense of humour differs.”

By the end of winter, her relationship with her soldier boyfriend, Desmond, had degenerated into a letter-writing exercise, continued by her out of sympathy. His letters arrived infrequently, in batches, and practically unreadable due to military censorship. “I often wonder just how much Desmond has changed, for it will soon be two years since I saw him.”

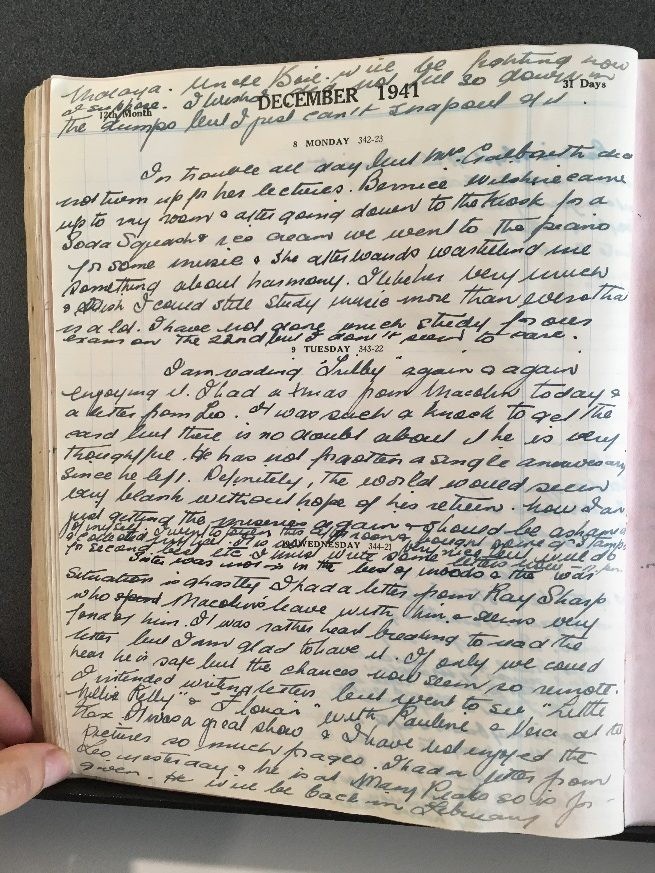

Page of Elvie Geissmann’s 1941 diary. State Library of Queensland collection. Image courtesy Debbie Terranova

Letters from her brother in Europe had ceased. “We still have had not a word of Macolm and I can’t think what can be the matter. Mum must be terribly worried by now.”

On 9 November 1941 she finally received the dreaded news. “The worst has happened. Macolm is missing over Cape Gris-Nez12 ‘as a result of enemy action’.”

No further information about her brother was forthcoming. One month later, she received a letter from his R.A.A.F. colleague, a fellow pilot called Ray Sharp who had gone on leave with Macolm and who “seems very fond of him. It was rather heartbreaking to read the letter but I am glad to have it. If only we could hear he is safe but the chances now seem so remote."13

On 7 December “Japan has declared war on Britain and America and has been bombing American bases”. At Christmas time “the hospital is sandbagged now almost everywhere and all the windows papered.”

A few pages later, the diary ends.

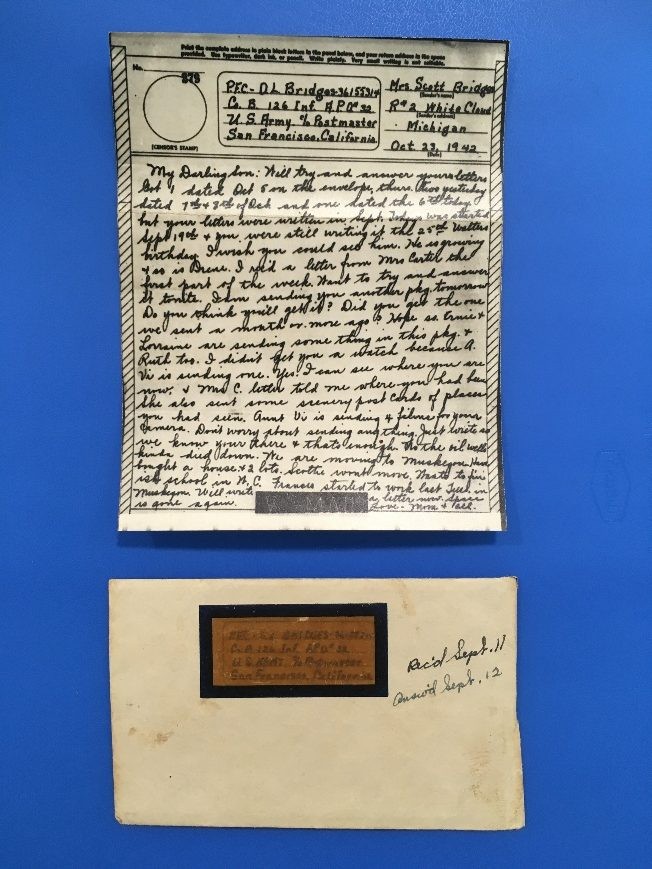

“V mail” letter to Roy Bridges from his mother in Michigan. State Library of Queensland collection. Image courtesy Debbie Terranova

Biographical notes enclosed with the diary reveal what happened next. Elvie met a U.S. soldier, Roy Bridges, while he was a patient at the hospital. He had been seriously wounded in the southwest Pacific in December 1942. They became engaged in October 1943, were married in September 1944, and Elvie departed Australia as a war bride in 1946. In America, the couple raised their five children in Michigan. Elvie Bridges continued her career as a registered nurse at Hackley Hospital for over forty years14. When her father was visiting in 1962, he had an accident that rendered him blind. She subsequently recorded both the family history and the history of Tamborine Mountain from his memories15.

Elvie died on 20 July 2014 in Muskegon, Michigan. She was 93. Her diary can be viewed at State Library of Queensland.

Debbie Terranova has a QANZAC 100: Memories for a New Generation Fellowship for 2018-19. Her research project is Queensland women and war: a multicultural perspective of the experiences of female civilians during World War Two.

1 It was a condition of employment that trainee nurses lived-in at accommodation provided by the Brisbane General Hospital for the duration of the three- or four-year training period.

2 During WWII, Australian-born citizens were referred to as “British subjects” and were “British born”.

3 Bridges, Elfriede (nee Geissmann). “The History of Tamborine Mt., as remembered by B.R. Geissmann”. Unpublished manuscript of her father’s memories. SLQ, Box 9224.

4 Colloquial term for the cinema.

5 Twenty-four shillings and eight pence, the equivalent of $2.47.

6 Fortitude Valley, a major shopping precinct in Brisbane at the time.

7 Sixteen shillings and eleven pence, the equivalent of $1.70. Not much cash remained for the rest of the fortnight.

8 Twelve shillings and eleven pence, the equivalent of $1.30. This was more than half Elvie’s fortnightly wage.

9 A fellow nurse.

10 Gonorrhoea.

11 The showgrounds are opposite the Brisbane General Hospital and are bounded by Bowen Bridge Road, Gregory Terrace, Brookes Street, and O’Connell Terrace.

12 Cap Gris-Nez is in France, about 30 kilometres south-west of Calais.

13 The Australian War Memorial shows Sergeant Bernard Macolm Geissmann’s date of death as 6 November 1941 and his place of death as ‘Off France’.

14 https://obits.mlive.com/obituaries/muskegon/obituary.aspx?n=elfriede-bridges-elvie&pid=171820628&fhid=21046. Accessed 26 February 2019.

15Ibid. Bridges, Elfriede.

Further reading from Debbie Terranova

View the collection:

27032 Geissmann Diary and Bridges Correspondence

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.