A brief history of NAIDOC Week: from protest to celebration

By Anna Thurgood - Engagement Officer, State Library of Queensland | 9 November 2020

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander material is accessed and used in accordance with State Library's Protocols for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collections. Also, note that in some communities this material may be culturally-sensitive because it may cause sadness or offend some people due to the use of words and descriptions used in the past but considered inappropriate today.

By the time the original NADOC (National Aborigines Day Observance Committee) was formed in 1957 there was a long history of lobbying and protesting for Aboriginal rights in Australia. Even before the 1920s groups were regularly boycotting Australia Day, protesting the status and treatment of Aboriginal people. It is important to remember this was a time where every aspect of an Aboriginal person’s life was controlled under various ‘protection’ and ‘assimilation’ acts in force around the country. However, locally organised Aboriginal groups began to recognise that the wider Australian public did not even know about the boycotts, and they resolved to be more active and vocal.

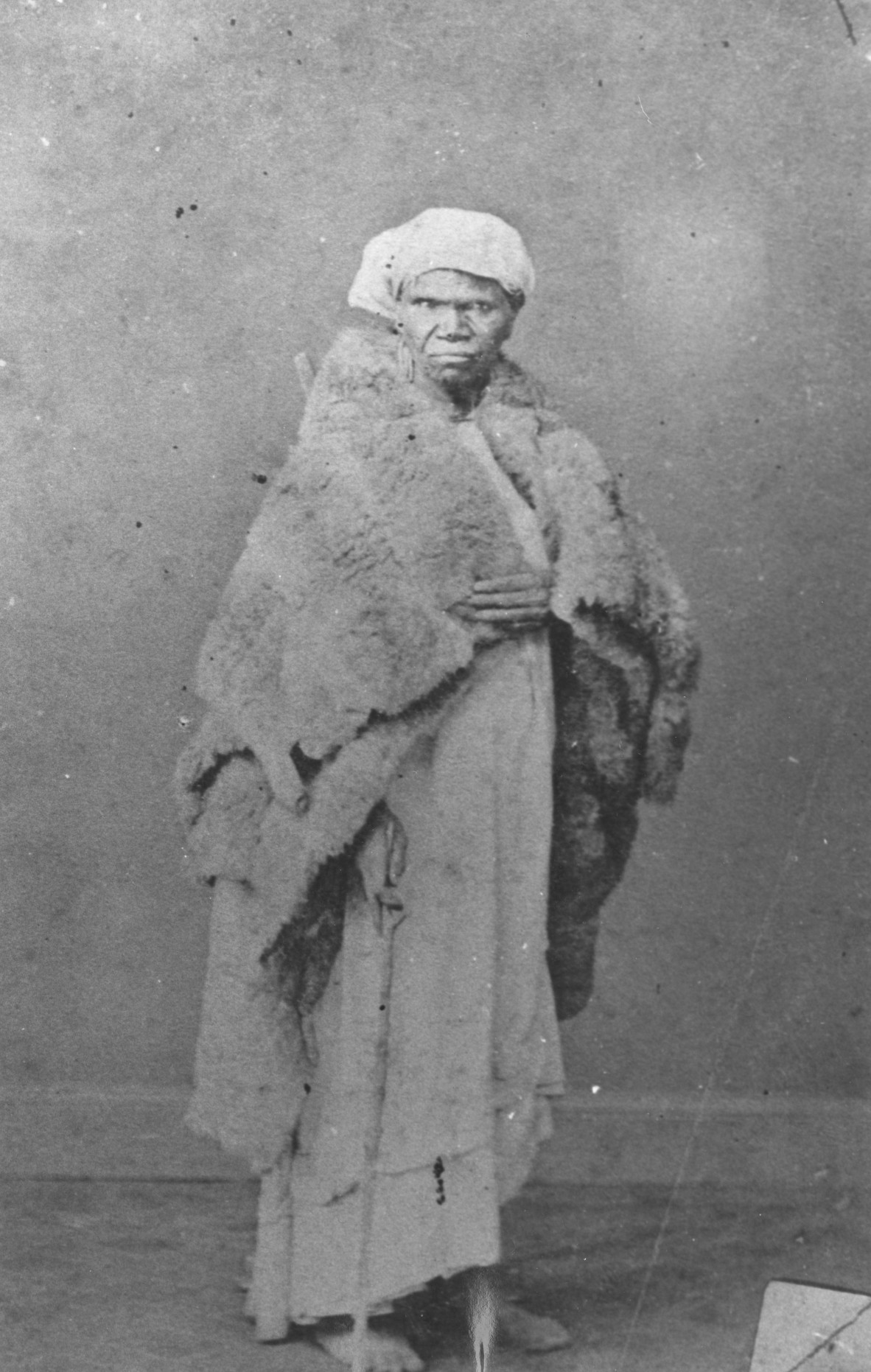

Aboriginal woman wearing fur, c.1870. Photographer unknown. Negative no: 33800. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

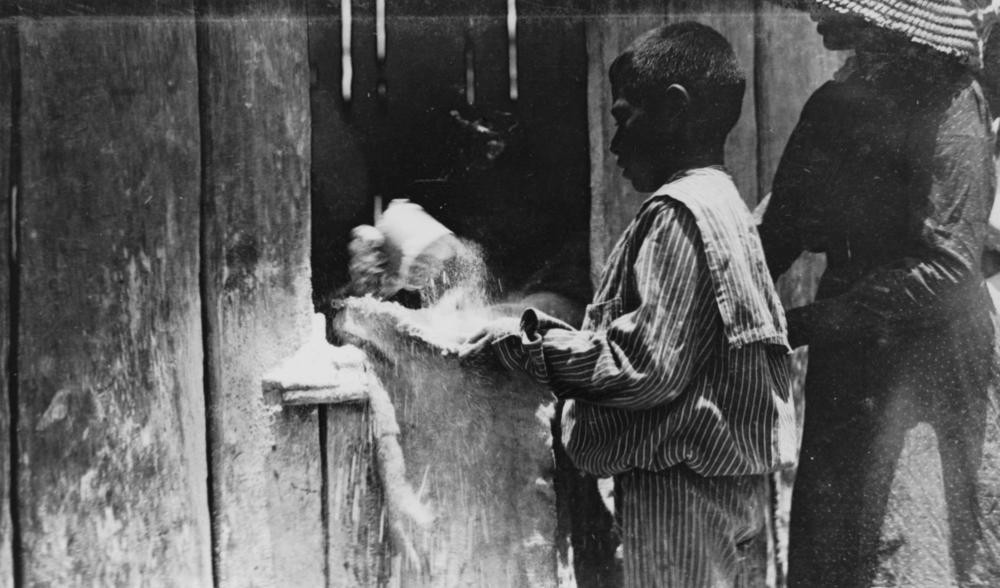

Receiving flour at Barambah Aboriginal Settlement, 1911. Will Stark. Negative no: 130675. John Oxley Library. State Library of Queensland.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s several new organisations emerged, such as the Australian Aborigines Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1924 and the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) in 1932. Unable to make much headway, the AAPA had to abandon its work in 1927 due to police harassment. However the work of this and other organisations, which culminated in the momentous Day of Mourning, became the inspiration for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activism throughout the rest of the 20th century.

One of the first major civil rights gatherings in the world occurred in Sydney on Australia Day, 1938, which was also the 150th anniversary of the landing of the First Fleet. Protestors marched through the streets and this was followed by a congress of over a thousand people. Known as the Day of Mourning, the following resolution was moved that day:

There were other outcomes from this day. One was a deputation sent to the Prime Minister, Joseph Lyons. Led by William Cooper, the group presented Lyons with a proposal for a national policy for Aboriginal people. This was rejected because the Government did not hold any constitutional powers in relation to Aboriginal people. Another outcome was that the Day of Mourning became an annual occurrence, held on the Sunday before Australia Day, in recognition of the terrible treatment of Aboriginal people and the resulting loss of culture and identity following the colonisation of Australia. The AAL had even been able to persuade many religious denominations to declare the day ‘Aboriginal Sunday’ to serve as a reminder of the unjust treatment of Aboriginal people.

Aboriginal Sunday continued to be commemorated throughout the 1940s and into the 1950s. It was decided in 1956 that the day should be broadened in its focus – to not dwell purely on protest but to also celebrate the diversity and vibrancy of Aboriginal culture. The Day of Mourning was changed to Aborigines Day and moved to the first Sunday in July.

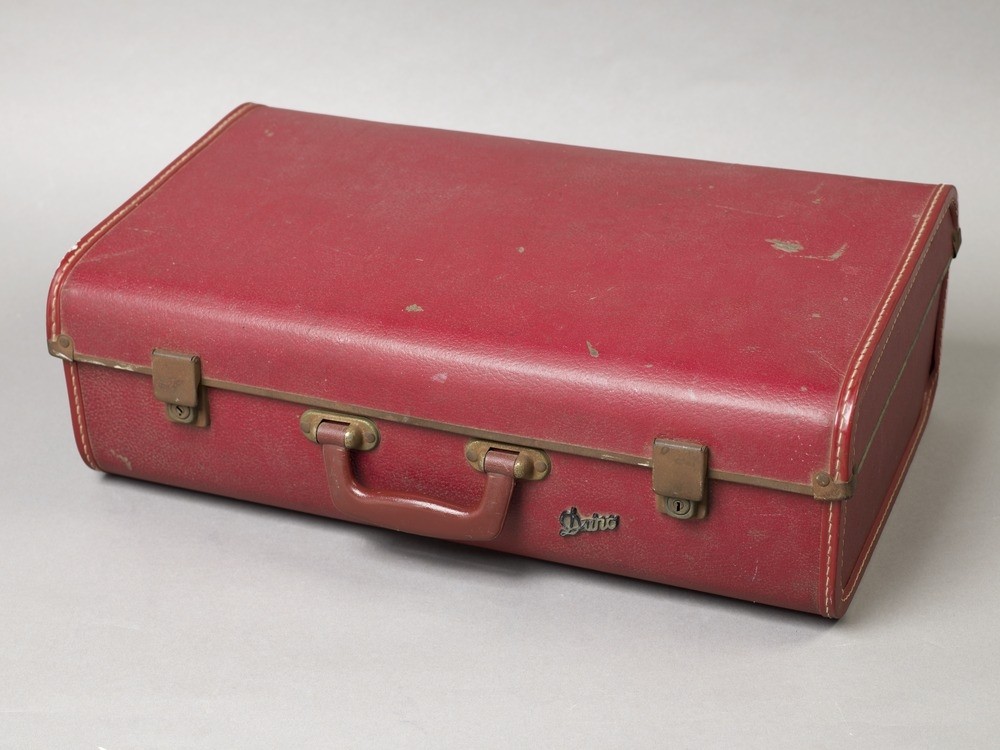

Lambert McBride’s suitcase, date unknown. Accession 7481 Lambert McBride collection 1963 – 1997. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

Lambert (Stan) McBride was the Queensland President of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) and played a central role in ensuring the campaign leading up to the 1967 referendum was a success.

In 1957, with the support and cooperation of state and federal governments, churches and major indigenous organisations, a National Aborigines Day Observance Committee (NADOC) was established to organise and oversee the celebration of National Aborigines Day, which was moved to the second Sunday in July. In 1974, the committee became comprised solely of Aboriginal people, some years after the 1967 referendum which saw the Constitution amended to allow the Commonwealth to make laws for Aboriginal people and include them in the census. And in 1975, the committee decided to expand the day to a whole week of celebration. They were, however, unsuccessful in their bid to have National Aborigines Day made into a public holiday for all Australians.

Protestors marching, Melbourne Street, South Brisbane, March 2012. Hamish Cairns. Image no: 28529-0001-0029. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

In 1991, NADOC was expanded to recognise Torres Strait Islander people and culture, becoming NAIDOC (National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee) as we know it today. Around this time the committee also decided to choose an annual theme, to reflect the most important issues or events each year. In 2020 the theme is “always was, always will be”, a catch-cry which has often been seen at civil rights protests in the last two decades. It aims to remind all Australians of the rich cultures that existed long before the arrival of Captain Cook and the First Fleet. Recognising the truth of Australia’s past and acknowledging 65,000 years of continuing culture and heritage is something the committee hopes all Australians can celebrate, because it makes Australia one of the most unique countries in the world.

Distant view of fish traps off Murray Island, 1957. Wilhelm Rechnitz. Image no: 6341-0001-0012. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

These fish traps, which have been used and maintained by Mer (Murray) Islanders for generations, is evidence of the relationship between people, land and sea that stretches back for millennia in Australia and continues to this day.

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.