Billy Sing, Queensland’s WWI “Crack Sniper”

By Elise Weightman, Visitor Services Assistant, Anzac Square Memorial Galleries | 12 April 2021

William Edward “Billy” Sing was born in Clermont, Queensland in 1886 and enlisted for service in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in October 1914. Though Australian-born, Sing was of Chinese ancestry, with a Chinese-born father. During World War I (WWI), Australia’s Racial Discrimination laws meant that men deemed “not substantially of European descent” (a classification that included “Asiatics” and “Natives”) could be rejected from enlisting in the defence forces. Sing, however, enlisted early, was accepted by recruiters and became one of at least 200 Australians with Chinese heritage who served in the AIF in WWI, despite the discriminatory policies of the day.

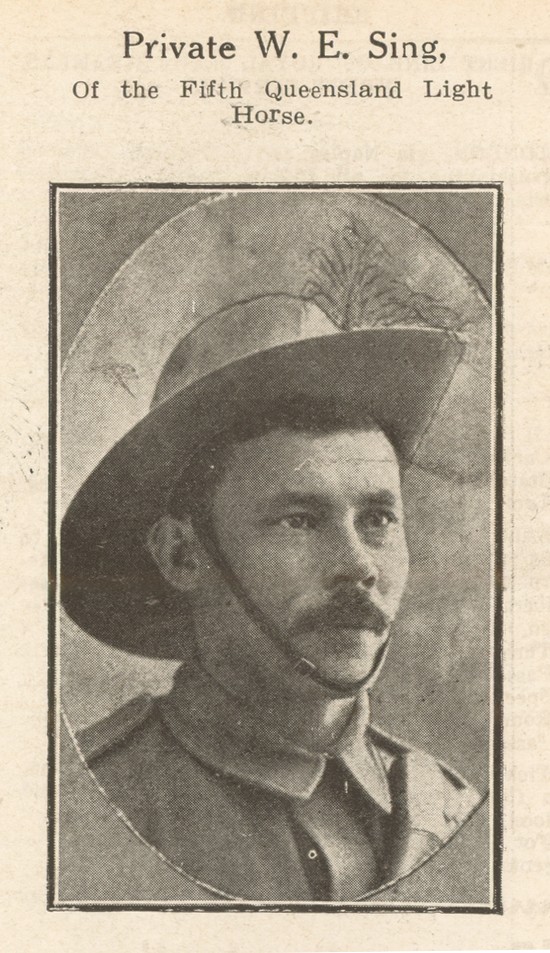

IMAGE: Soldier Portrait of Private W E Sing, from The Supplement to the Queenslander, 22 Jan 1916, SLQ Image No. 702692-19160122-0028

Prior to the war, Sing had been employed as a stockman, and had also developed excellent skills as a “dead shot” marksman, and with this background he was assigned to the 5th Light Horse Regiment.

IMAGE: Detail from the plaque for the 5th Light Horse Regiment at the Anzac Square Memorial Galleries

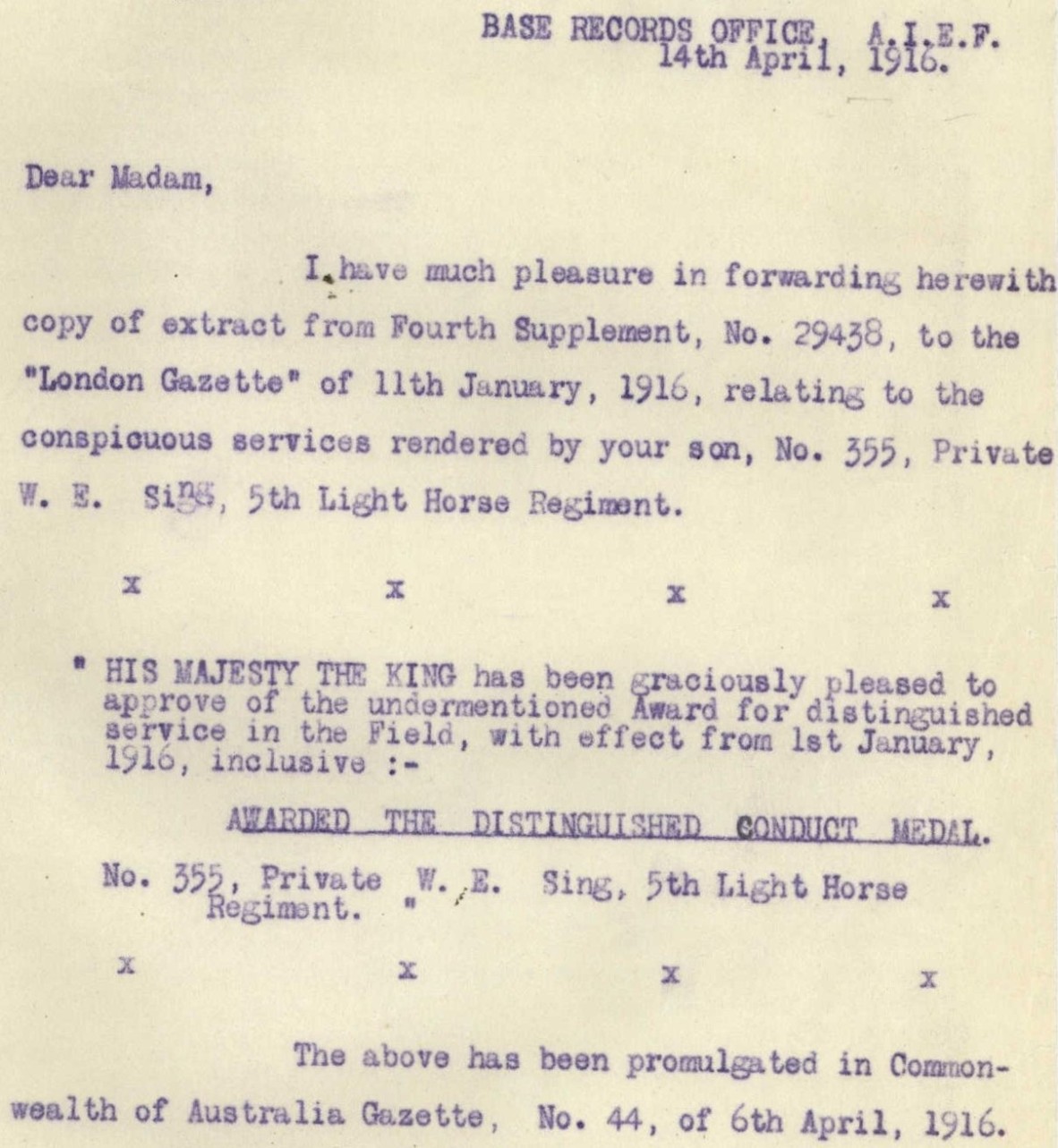

By May 1915, the regiment had deployed to the frontlines on the Gallipoli peninsula, and there Sing soon established a reputation as a lethally effective sniper. Accounts of Sing’s service report he would take up his position early, remain motionless and silent until his targets revealed themselves, and then shoot with deadly accuracy. For his contribution, he was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal:

“for conspicuous gallantry from May to Sept 1915, at Anzac as a sniper. His courage and skill were most marked and he was responsible for a very large number of casualties among the enemy. No risk being to[o] great for him to take”.

IMAGE: extract from service record of William Sing, National Archives of Australia: https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=4375195

That “very large” number is estimated at anywhere from 150 to 300 enemy “kills”, a record which also earned Sing monikers like “The Assassin” or “The Anzac Angel of Death”.

After the end of the Gallipoli campaign in December 1915, Sing was hospitalised in Egypt with the mumps, before being reassigned to the 31st Battalion and eventually deploying to the Western Front in 1917. There Sing adapted his skills to a new style of warfare and again distinguished himself through his actions; he was mentioned in despatches more than once and awarded the Belgian Croix de Guerre in 1918 following operations at Polygon Wood. He was also wounded multiple times (including gunshot wounds to the leg and back), gassed, and afflicted with other illnesses.

During one period of convalescence in the UK, Sing met and married a woman named Elizabeth Stewart in Edinburgh in June 1917; however this union unfortunately did not survive long after the war and it is unclear what became of Elizabeth after Sing returned to Australia.

Sing came home to a “hero’s welcome” when he arrived back in the town of Proserpine in November 1918, being greeted by a large turnout of locals and a Citizens’ Band playing “See the Conquering Hero Comes”. (See more of this Townsville Daily Bulletin article on Trove: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article62633886)

After 1918, Sing pursued various livelihoods, from working a soldier settlement farm to gold mining, but these ventures proved difficult for him and were ultimately unprofitable. He was also dogged by his wartime injuries throughout the remainder of his life. By 1942, Sing had moved to Brisbane, where he lived near his sister. He was residing in a boarding house on Montague Road in West End when he died of a ruptured aorta in May 1943, aged just 57. A news article made brief mention of his passing:

IMAGE: Extract from the article “Crack Sniper Dies Here” published in The Courier-Mail, 22 May 1953. See more of this article on Trove: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article42045240

Sing was buried in Lutwyche Cemetery, where much of his legacy lay buried with him until the 1990s when a local journalist and then the RSL and others took up the cause of Sing’s story. Since then, a number of memorials and events have been created to acknowledge Sing’s service, including an updated plaque placed on Sing’s grave, which now contains the following epitaph:

“His incredible accuracy contributed greatly to the preservation of the lives of those with whom he served during a war always remembered for countless acts of valour and tragic carnage.”

Further reading:

Another SLQ blog story about Chinese-Australians from Queensland in WWI, the Shang brothers: https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/blog/chinese-anzacs-shang-brothers-cairns

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.