The backyard, free-standing sleep-outs of WW II: Are there any left?

By JOL Admin | 13 January 2018

The Queensland backyard structure we most associate with WW II is the air raid shelter but there was another. It was one of the solutions to the lack of accommodation for war workers and problems with getting adequate building materials and builders during WW II. From 1943, it was strongly promoted to householders. Recently, a library researcher found out about it from a letter written by a family member during the War and wanted to know more. The newspapers, now available online in Trove, kept people informed at the time.

Courier Mail, 4th September 1943, p.4

Promotion of the sleep-out

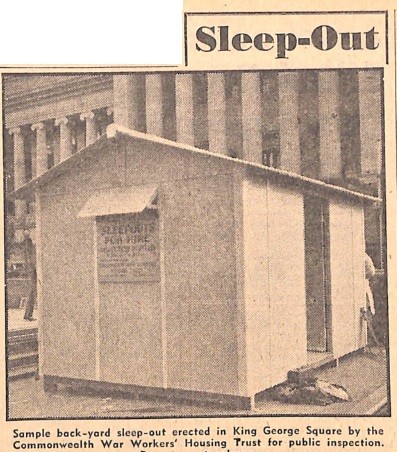

By August 1943, it was announced that sleep-outs would be built in Brisbane at the rate of 2-3 a week. The following month, a model of the proposed sleep-out was put on display at a central point: in King George Square, Brisbane. The Courier Mail covered the display. Folders explaining the scheme were available from the attendant on duty all day, or from the War Workers Housing Trust. It was said to be especially suited to the Queensland climate. As the sleep-out also survived a storm, its weather-proof qualities were also emphasised. Public inquiries revolved around other uses: whether the attendant came with the hut or it could be used as temporary accommodation for girlfriends. The attendant tested the mattress springs by bouncing on it. At the end of September, it was announced that the Real Estate Institute of Queensland would take over responsibility, continue with the King George Square display but furnish the sleep-out more attractively.

What was the sleep-out?

At a cost of approximately £45, it was made of fibro-cement, measured 12ft X 9ft with a window and a door, built around a wooden frame and floor as a standalone construction. It had 2 ventilators, and if necessary, steps. It would accommodate 2 workers, contained 2 single beds, 2 built-in wardrobes and a dressing table. There was a single electric light and switch. The War Workers Trust funded electrical connection up to a cost of £2. Linen for the sleep-out would be provided without coupons. The sleep-out was essentially a bedroom so the workers would eat with the family. As the sleep-out was regarded as a chattel, it was not necessary, although desirable, to get planning permission.

The property owners could rent these sleep-outs at 15/- (shillings) a month and charge enough (18/- was suggested) to make a profit. There was a minimal rental period of 6 months. At the end of the war, it was proposed that the property owners could buy the sleep-outs from the government, at a reasonable charge.

Criticism of the sleep-out

The limited definition of war workers restricted the use of it unfairly. Government regulations proved a problem. National Security regulations defined “war workers” as those involved in the “munitions of war”. This excluded those working in canning or clothing factories, responsible for the soldiers’ clothing and food. Landlord and tenant regulations also caused concern as the demand for accommodation increased and offers to participate in the scheme dwindled.

One airman’s wife wrote to the editor of the Courier Mail that more hostels would be as economical and less of a problem to a housewife already struggling to get basic foods and who would have to prepare meals for the workers as well as pay rent to the government. Although it had been suggested that providing sleep-outs to workers could be imposed on householders she doubted that it could be enforced. By March 1944, sleep-outs became available for use by all essential workers whose families were overcrowded and by childless married couples, only one of whom need be an essential worker. Attention increased on returned servicemen and their families as well as the post war housing needs.

What happened to the sleep-outs?

Were they removed or demolished? Did they become children’s playhouses, garden sheds or granny flats? Are there any photographs or memorabilia of them? Are there any stories about them? Are there any left?

Can you help us find the answers? Leave a comment on this blog or email us at visitorservices@slq.qld.gov.au

Stephanie Ryan

Research Librarian

State Library of Queensland

More information

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper

Ask Us service - /services/ask-us

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.