Archives reveal more history of Hornibrook innovation in the building of Sydney Opera House.

By Julie Hornibrook, Research fellow 2015/16, QBLHOF | 3 November 2021

Guest Blogger: Julie Hornibrook

The saga of the building of Sydney Opera House is well documented, culminating in resignation of the original architect, John Utzon. The Opera House was finally opened many years later in 1973, long after Utzon first won the design competition in 1955. During the construction phase Australian author Patrick White described the construction site as evoking the ruins of Mycenae, in Ancient Greece. His feelings evoke concern people already had about delays in the early 1960’s and doubt about whether a building of such a grand concept could ever be achieved.

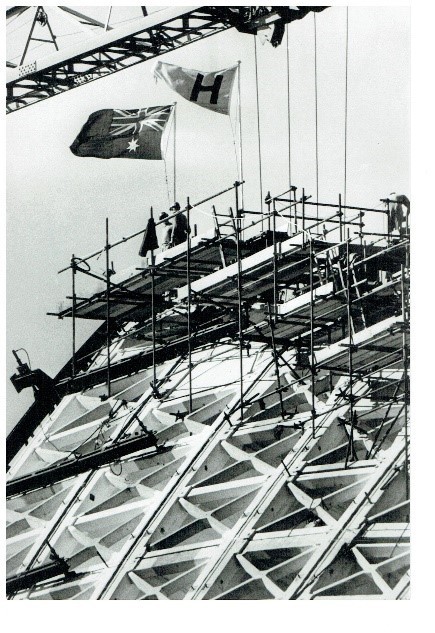

Construction of the Sydney Opera House, 1965. Max Dupain and Associates records and negative archive : uncommissioned Sydney Opera House construction photographs, 1965-1972. File identifier: DByLQxvkP3E0b.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy of Max Dupain and Associates

Indeed, how was it to be built? The building was immensely complex in design and structures such as the magnificent roof shells we know today, had not been built before. Arup was the engineering firm contracted and to find a building company the team turned to Queenslander, Sir Manuel Hornibrook, (or ‘MR’ as he was known) whose company had an international reputation for being the top civil engineering contractor in Australia. They needed a contractor who could be flexible and take a deeper and more intelligent interest than could be obtained by competitive tendering. They realised it would not be straightforward and they would need to feel their way during construction of the Opera House if it was ever to succeed.

From 1962 Hornibrook was awarded the contract for Stages II and III. The Sunday Telegraph headlined: ‘He’ll put the roof on the Opera House.’ MR, my grandfather, was 69 years old at the time. They said he was forthright, honest and proud, and while he demurely said it would be egotistical to say they were the only ones in the world who could do the job, he couldn’t think of any others who could! Just the kind of challenge he would have loved.

MR was known for the drive that built his company and he had the character who was ‘capable of undertaking civil engineering and building contracts of any magnitude and nature.’ This outlook was clearly going to be a key ingredient in facing the challenges needed to bring together design, imagination, engineering, skills and courage. MR’s true grit showed with his outlook that ‘it’s not the jobs you start that count, it’s the ones you finish.’ He was at his best when projects were tough ones. He was proud that he had never failed to complete a project and he knew it was not the time it takes to complete but the will to do so that makes a real difference. Proof was in the pudding with achieving the building of the Hornibrook Highway in Queensland, especially during the Depression when people said it couldn’t be done, and the Story Bridge and William Jolly Bridges, each with immense challenges. 100 more bridges were testimony to the skills the company had in building with concrete and steel and problem solving to get lasting results. This know how would serve well in meeting the challenges of building the Opera House roof.

A construction site – unknown person with Sir Manuel Hornibrook and his son, Clem. From collection of Julie Hornibrook

As the leading construction company Hornibrook attracted the best skills in the business. Corbet Gore became construction manager for Stages II & III, transferred directly from his role as manager for the building of the Commonwealth Avenue bridges in Canberra. George Boulton, a civil engineer who had worked with MR for many years was co-opted to the project. Joe Bertony, a brilliant engineer who first worked with Hornibrook in Queensland as a migrant after the war, did over 30,000 mathematical calculations by hand, before computers, to work out how much stress could be applied within the roof construction. Each one was proven to be totally accurate.

An exciting new development on the history of the collaborative processes of problem solving has been found by a research team including Luciano Cardellicchio (UNSW), Paolo Stracchi (University of Sydney and Paolo Tombesi (EPFL, Switzerland). They have been exploring hundreds of newly discovered design drawings in the NSW Archives of the casting procedure for the moulds developed by Hornibrook’s for the concrete ribs comprising the roof shells to be made and erected. However, once the roof had been achieved, the onsite factory to cast the moulds was dismantled and forgotten over time. This is new and exciting tangible evidence of the extent of the Australian innovation in the design and construction process of the Opera House. The team has developed a video to describe their findings so far.

Many thought it would be impossible to build the roof shells. MR was known for designing equipment as needed to fit a job, seen as a real craftsman and construction engineer as well as a contractor. In many jobs he played a major role in conception and design of special plant, methods and procedures. This became the company culture and enabled the ingenuity needed to meet the demands of building the Opera House. For example, Corbet Gore also pioneered the use of epoxy resin to glue the precast units. Joe Bertony is credited with designing the movable steel erection arch to lift the precast ribs to the Opera House roof.

The recently located design drawings found in the NSW Archives will provide a lot more information and stories from the building of the iconic Sydney Opera House. The research team hope to digitise the drawings and aim for an exhibition for the 50th anniversary of the opening coming up in 2023. The stories will bring to light more of the inventions of MR and the Hornibrook company which made such a creative contribution to this lasting Australian story.

Workers on scaffolding during Sydney Opera House construction.

Julie Hornibrook was the 2015 Queensland Business Leaders Hall of Fame fellowship recipient. View her showcases on three Hornibrook projects here.

Other blogs by Julie Hornibrook:

Comments

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.